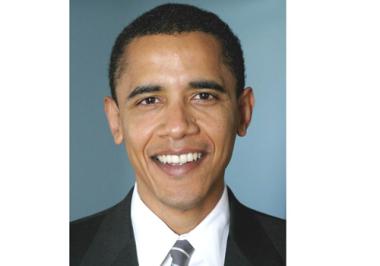

The controversy over Barack Obama's admiring mention of former President Ronald Reagan thrived in recent days, fed and nurtured by Hillary Clinton and her allies. Clinton used her rival's comments about Reagan and the Republican Party to assert that he must think policies like "huge tax cuts for the wealthy" are a good idea.

Her campaign also arranged a media conference call in which one of her supporters, Congressman Barney Frank, declared it "baffling" that Obama would "speak so favorably" of Reagan.

But there's no shortage of precedent for a Democratic candidate lauding a reactionary leader. And Clinton should know it.

On the day before the New Hampshire primary, she referenced Margaret Thatcher, initially praising the former British prime minister simply for having "stepped up to the plate" on global warming. But Clinton went on to imply a similarity between Thatcher and herself: in essence, that both were effective even at the cost of personal likeability.

"We had one leader—I don't know how likable she was—we had one leader who made it a priority and got the job done," she said.

This was hardly a comparison that Clinton pulled out of thin air. Her campaign aides have often posited almost identical ideas.

Mark Penn, perhaps Clinton's closest adviser, last fall presented a more elaborate version of the argument that Clinton would deliver in the snows of New Hampshire. Referring to the importance or otherwise of likeability, Penn told the Daily Telegraph of London: "I think 'buddy potential' is way overrated. It's not who you want to have a beer with, it's who you want to have as president or prime minister. The Margaret Thatcher experience showed pretty clearly how the Conservative Party did so much better with strength and leadership. In the U.S., people realize increasingly that running for president is not an American Idol-like contest."

By the standards Clinton and her campaign have applied to Obama's comments about Reagan's effectiveness, it was a fairly disquieting observation. And as is the case with Reagan, Thatcher—a bitterly divisive figure firmly rooted in the hard right—offers little that should appeal to the base Democratic constituency Clinton is courting.

Penn and his ilk make much of Thatcher's electoral effectiveness. It's true that she led her Conservative Party to three consecutive general election victories, in 1979, 1983 and 1987. But that achievement becomes less impressive the more closely it is examined.

Thatcher's victories came against a demoralized Labor Party that struggled by turns with a powerful far-left faction that seemed intent on committing electoral suicide and, from 1981, with a challenge from a new center-left party, the SDP.

Despite these advantages, Thatcher's party never came close to winning an overall majority of the votes cast. The Conservatives' peak performance under her leadership came in her first election at the helm, and even then they were supported only by 43.9 percent of voters.

By the twilight of her tenure, in 1990, Thatcher was the most unpopular prime minister since polling began half a century earlier. Only 24 percent of Britons approved of her performance. Electoral victories aside, the Thatcher record should be abhorrent to someone with Clinton's professed beliefs.

The defining domestic struggle of Thatcher's premiership came in the mid-1980s, when the National Union of Mineworkers went on strike. She prevailed after a yearlong struggle, helped in equal measure by a powerful and shrill right-wing press and by the autocratic personality of the miners' leader, Arthur Scargill.

But, especially in retrospect, the confrontation has come to be seen as the centerpiece of a long Thatcherite campaign to crush organized labor. It is also the reason why Thatcher's name to this day is generally preceded by epithets when spoken in the former mining communities of northern England, Scotland and Wales.

Thatcher's social policies were scarcely any more enlightened. She led the charge to pass the homophobic "Section 28." The statute—later repealed by Tony Blair's Labor government—sought to prohibit state schools from teaching the "acceptability" of homosexuality and banned local authorities from "promoting" it.

She had no problem playing the race card when the situation demanded it. As leader of the opposition in 1978, with the Tories facing a seepage of support to far-right racists like the British National Front, she said that people in Britain are "really rather afraid that this country might be rather swamped by people with a different culture." (The tactic of slyly but clearly pandering to racial prejudice would of course be echoed by her great friend Ronald Reagan, who opened his 1980 general election campaign with his infamous "states' rights" speech in Philadelphia, Miss.)

The Thatcherite mind set diverges in every way from the values for which Clinton claims to stand. Clinton's bromide about how "it takes a village to raise a child" would find no sympathy with Thatcher. One of the British prime minister's most notable assertions was that "there is no such thing as society."

Clinton and her aides would doubtless protest that they are enthused not by Thatcher's ideology but by her personality. On the day Clinton announced her candidacy last year, her campaign chairman, Terry McAuliffe, told Britain's Sunday Times that Clinton and Thatcher would be very different on policy, but added admiringly that they "are both perceived as very tough." The notion of Clinton as America's Iron Lady may be useful as her campaign searches for an antidote to the perception that she shifts with the prevailing wind. But it is worth remembering that the steel in Thatcher's soul led her to disaster as often as to triumph.

Her unyielding response to the 1981 hunger strikes in Ireland fed the growth of the Sinn Fein party, to which she was implacably opposed. Much later, her refusal to bend on her proposal for a poll tax led to mass protests and rioting in Trafalgar Square, and, ultimately, to the end of her premiership.

A tough role model, indeed.?