When I sat down with the editors of The World, the joint BBC/WGBH national radio program, my original idea was to embark on a series of stories about race relations across the globe. But the more we thought about the issue of race and all the social constructs concomitant to this issue, the more we realized that the stories we envisaged were about something much broader: color. The mission of the The Color Initiative, is to examine complex global issues of politics, culture, history and society through the framework of human perceptions and experiences related to skin color.

Color often explains what race cannot. For example, among the stories we plan to examine is the issue of “whitening” in virtually racially homogenous nations across Asia, principally China, Taiwan and Korea, and the social and political explanations for its mass appeal. But that’s not where we began. The first report in the on-going series looked at the marketing campaign of Benetton, which mixes business with socially conscious messages focusing on diversity of all sorts, including color. Benetton’s messages are now coming up against growing anti-immigrant realities in Europe, including the dominant presence of the Northern League in the very Italian city where Benetton is headquartered: Treviso.

The story was motivated by an experience I had had years earlier. Driving south from the Dolomites to Venice several summers ago, I had passed dozens of identical billboards advertising the United Colors of Benetton. An idyllic picture of interracial friendship was shattered near Belluno. Someone had thrown a rock through the wallpapered head of a charcoal-colored boy and scribbled in Italian: Questi colori non mischiano (Miss-kia-no): “These colors do not mix.”

Dolomites to Venice several summers ago, I had passed dozens of identical billboards advertising the United Colors of Benetton. An idyllic picture of interracial friendship was shattered near Belluno. Someone had thrown a rock through the wallpapered head of a charcoal-colored boy and scribbled in Italian: Questi colori non mischiano (Miss-kia-no): “These colors do not mix.”

Since that time, Italy like the rest of Western Europe has experienced a surge in immigration with a blend of nationalities and colors unprecedented in modern European history: Senegalese, Moroccans, Bulgarians, Romanians, and Nigerians among others. And their presence has sparked a major backlash. My plan pending future funding is to take a closer look at the experiences of Roma and Senti people, who often are referred to as “black” as a way of designating their lower social status in European societies.

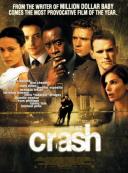

For many people outside the US, race is an essential part of what defines America. And it is Hollywood that is helping to supply many of the images. That was the subject of the second Color report on the World.

For many people outside the US, race is an essential part of what defines America. And it is Hollywood that is helping to supply many of the images. That was the subject of the second Color report on the World.

Two of the more talked about stories in the series thus far also concerned immigrants, but in this case immigration to the United States. Between 1881 and 1920 about twenty-four million immigrants from southern and eastern Europe put down roots in the US. In color terms they were regarded as neither black nor white, but as a sort of "IN-BETWEEN” people -who would gradually become white -often after petitioning to the courts. To be white was to be more privileged in the context of America’s strict racial pecking order. That was the subject of Part One of How Europeans Became White. Part two of this report begins in the 1970s with a new wave of olive, tan and beige skinned immigrants who arrived to these shores seeking the same opportunities. But Americans’ perceptions of color had become far more complex by then says David Roediger, author of Working Toward Whiteness:

Acceptance as fully white for this group of immigrants is very open to question: To Islamic immigrants or people who look like they might be of Islamic faith, particularly after 9/11. It’s open to question on the part of Asian immigrants because of the tremendous weight of the history of exclusion in the United States. Similarly but more complicated is the case with Latino immigrants (David Roediger).

That has been a common lament of many undocumented Mexicans in the United States, among others, who allege that liberty and justice for them differs dramatically from the treatment of European immigrants who also may be in the country illegally.

Two other reports in the series looked at color discrimination practiced by some American servicemen and women against Iraqis in Iraq (Coloring Iraqis) who are often demeaned as "Hadjis," "Camel jockeys," and "sand niggers." We also spoke to military educators who are working to address the broad implications of this issue. Our story on Malaysia’s ethnic Indians explored the growing movement in that country to end color hierarchy that reigns over all aspects of society, though ostensibly there is no color discrimination in Malaysia.

In the coming months the Color Initiative will also examine the role of mestizos in Mexico and look at the provenance of Puerto Rico’s claim to be the land of the "rainbow people" and what that means in practice. The most ambitious aspect of the Initiative will be a multi-part series on Color Across Asia.

W.E.B. DuBois observed more than 100 years ago that the problem of the 20th Century "is the problem of the Color Line.”" As we have witnessed in a Democratic Party primary election that began with so much hope and descended into racial acrimony, and with ethnic and racial tensions stirring from Tibet to Bolivia, it’s clear that the problem of the color line is also the problem of the 21st century, and it knows no borders.

–Phillip Martin, Correspondent for The Color Initiative