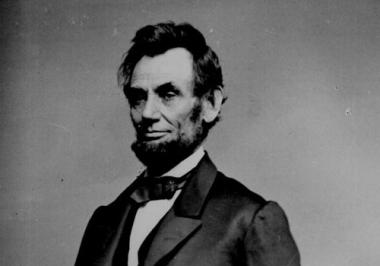

"Sockdologizing" was a fashionable slang word in the 18th and 19th centuries, and it means stunning, forceful or decisive, as a blow. It's one of the last few words President Abraham Lincoln heard before he was shot.

Lincoln and his wife, Mary, seated in a raised opera box at Ford Theatre, were watching a performance of the farcical play Our American Cousin at the behest of leading lady and company manager Laura Keene. As Harry Hawk, the actor playing Asa (the bumbling American cousin), delivered his most comical line, "Don't know the manners of good society, eh? Well I guess I know enough to turn you inside out, old gal—you sockdologizing old man trap," John Wilkes Booth fired a carefully planned shot amid raucous laughter. Lincoln was not killed instantly—he lingered for some 24 hours. That night, Ford's Theatre played host to America's first tragedy, according to librettist and UC Berkeley professor John Shoptaw.

The drama surrounding the assassination and the impact it had on our young country, raw with Civil War wounds, is the subject of the new Our American Cousin, an opera by Shoptaw and composer and Amherst College professor Eric Sawyer.

The first operatic endeavor for both, Our American Cousin is the result of 15-plus years of work. Sawyer and Shoptaw met in the early '90s while Sawyer (one of few musicians to be so honored) and Shoptaw's wife were junior fellows at Harvard. Shortly thereafter, Sawyer and Shoptaw decided to write an opera together. The discovery of Our American Cousin (the original play), coupled with Shoptaw's lifelong affinity for Lincoln, made the subject matter an easy fit.

"When I was in junior high, I wrote an essay titled, 'Will the Real Assassin Please Stand Up?'" said Shoptaw in an interview with the Advocate. "[A character] tried to go back and save Lincoln and shoot Booth. [Instead] the character ends up shooting Lincoln himself, because you can't change history."

The reason for Shoptaw's childhood fascination with Lincoln became clear to him many years later: Shoptaw's father died of a heart attack when Shoptaw was seven. "He was there one day and not the next," said Shoptaw. "So I guess I latched on to this father figure of our country."

At times a play within an opera, Our American Cousin moves step by step through that evening at the theater, beginning with the actors backstage readying themselves for curtain time. Keene reprimands the cast; Booth gives a fellow actor, John Matthews, a letter—which he didn't open until after the incident—claiming responsibility for the killing of Lincoln and stating his reasons for his actions.

In the second act, scenes from the original play are performed; Booth shoots Lincoln and makes his escape. The aftermath of the shooting and the melee that ensues comprise the third and final act. Much of the staging is historically accurate—Keene cradling Lincoln's head in her lap, Hawk running away instead of apprehending Booth when they come face to face onstage. But Shoptaw uses the libretto to incorporate a number of themes, including remembering (how the past affects us), dismembering (the war veteran amputees, the interrupted performance of the original play), forgetting (Keene used the art of theater to help patrons escape the realities of war) and guilt (shared by almost everyone, save, apparently, Booth).

"Hawk felt guilty," said Shoptaw. "Matthews felt guilty. [Keene] felt guilty because she had invited the Lincolns. Mary felt guilty because she loved the theater and brought the president. Abe felt guilty because of the war—he'd put this country through extraordinary suffering. All of this resides, for me, in the national guilt of slavery."

Shoptaw is quick to point out, however, that despite the ominous inevitability of Lincoln's assassination, this opera has its lighthearted moments, amplified by the use of supertitles. "I do anything in an opera to make people laugh," said Shoptaw. "I try to be funny. Supertitles will help people look back and catch the pun."

Sawyer decided to use Lincoln's demise as fodder for an opera because of its historical import. The Civil War had just ended, taking the institution of slavery in the United States with it. Lincoln had recently announced his intention to grant suffrage to freed slaves. This announcement was the final straw for the young actor John Wilkes Booth, who believed the American people would thank him for delivering them from Lincoln's folly.

People of all ages and races were affected by the war. Shoptaw and Sawyer chose to give some of those people—amputees, freed men and women, businessmen, nurses and female kin of veterans—voices as part of the chorus, whose members include local vocal notables as well as students from UMass-Amherst and Smith and Amherst Colleges. The chorus sings laments throughout the play for each of the main groups represented, and a final refrain, in which the chorus represents a present-day audience.

"They become the people who have come to the opera and are looking at this story so many centuries later, and how it really still is with us," Sawyer told the Advocate.

The women sing of gathering at dawn at the depot to hear names of the dead and wounded called out; the amputees sing about giving their limbs for their country. "The newspapers speak of a final disarmament," the chorus sings. "How come, when we already laid down our arms?"

The freed slaves sing of their northward trek; the nurses sing of caring for the wounded without wounding their own hearts. But perhaps the most powerful refrain belongs to the businessmen—who bear a resemblance to Halliburton and Blackwater CEOs—as they gloat over how the war has lined their pockets: "The war was kind to us/ we made a killing&/ please take our catalogue—it's so appealing/ but let's get back to work, the time is now/ there's money to be made/ we know, we made a killing."

Our American Cousin debuts at 7:30 p.m. June 20 and 3 p.m. June 22 at the Academy of Music, 274 Main St., Northampton. Tickets are $25-50; call (800) 595-4TIX or log on to www.ouramericancousin.com.