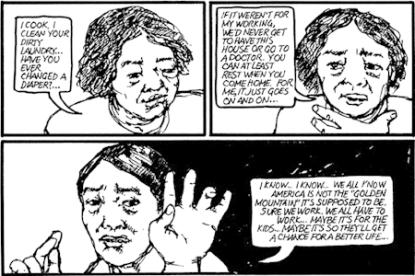

From Asian American Comic Book by Wen-ti Tsen, AARW, pg. 63

My last blog post ended with us suspended on the ledge of a 3rd-story window of an old Chinatown building. Cleaning up, after finishing a mural on the building’s side depicting the coming of Asians to Massachusetts, I espied below an older Chinese woman first noticing the image. She set her grocery bags down, and studied the painting. I had a flash realization of finding an audience and a form.

But, like 2-reelers of old, this ending was also the next beginning. I pondered: who was the rescuer, who the rescued?

Growing up in the West, I looked for expression in the majority cultures I lived in. Making art, I referenced Western models and appropriated mass-media images in my paintings in critiquing the society I saw.

Some years before the mural, working in political circles, I was asked to show paintings at a conference on emerging identity politics. When the African American star speaker breezed through the show, I was astounded to hear her pronounce to her retinue her take on the paintings: "Never seen so many white faces in one place in my life!"It did not change my work, but it made me reflect.

So later, working in Chinatown and the timely appearance of the older Chinese passerby led me to touch on a sort of identity.

Seeing this Chinese woman brought to mind some deep associations: first, of my mother (who died recently, but is always around 55 in my mind) in body shape and carriage; then, of the servant I hung out with, who taught me to iron and sew, whose cracked fingers and purple burnt welts from washing and ironing first touched me. And, this passing woman, seemingly overworked, heavily burdened, and looking for respite, evoked for me the China I left, of the past. It was an expanding circle of empathy that was propelled mostly by personal connectedness, and partly racial.

I can see: were this race-based identification to play out on a national scale, for example, in a country like China, were its animus to move a billion adherents, now exponentially those of WWI and WWII–it would be a terrifying prospect.

But, Asian Americans, living in the U.S., are a minority. They have faced a dominant culture that, for centuries, offered them only two options: an entry, if the men were obsequious and genial, and the women, submissive and pleasuring; or, be ghettoized as sneaky, inscrutable and alien. The Asian American movement, from 1970s on, constructed its own views of their identities, with a new reading of history, and truer representations of the lives of Asian Americans. And, the people are valorized, thus, looking into mirrors: there is no more Suzie Wong, yellow-faced Charlie Chan or buck-teethed Mickey Rooney.

Cultural nationalism and race-identity politics serve well as resistance correctives to a race-based dominant culture. Yet, as they are essentially reactive, and can turn separatist and reactionary, I do not believe they are to lead us to a better world.

So, this episode, too, is to end on a hanging note:

Years ago, returning to America after a 3-year stint teaching in Beirut, I could not find a job. With our first-born due in November, I spread my wares, and got hired by a preeminent billboard company. It was a union shop run on seniority. With no experience, I started as a helper–a ground-man hauling buckets, and repositioning 40-foot ladders.

By spring, I was upgraded to working on the swing-stage–a suspended scaffold with one man at each end pulling ropes–assisting a veteran picture-journeyman. He helped me do what was needed, but did not talk much. With an Irish name and Boston accent, I assumed he might have been somewhat of a racist. On a swing-stage, one relied on each other to do it right, in all weathers–we did not talk politics. All I knew was, on weekends, he worked on his house by the sea.

One fine day in May, we were on a job painting a Pan-Am ad on a 3-story-high billboard, on the roof of a 7-story building, overlooking the expressway. My job as helper was to paint the background and the 4-foot letters. I was not allowed to touch the almost-life-size Boeing 747 taking off. As the journeyman painted the reflections on the belly of the plane, my segment done, I stood against the 2×4-rail, face to wind, glad as a bird to have survived the winter.

As lunch break, we sat on the platform within talking distance.

Looking ahead, the man said: "Once I took a watercolor class at the Museum School. There’s a Turner at the Museum with a color-stroke just like that," gesturing towards where the sky met the harbor islands. "Hard to do."

I never regarded watercolors much (lionizing oil paintings instead)–but, after that, I looked more carefully.