As part of its sustainability initiative Northampton is undertaking a review of its zoning regulations. The planning board, a government agency that is appointed by the mayor with city council approval, will be charged with appointing the rezoning committee. I would like to add a cautionary note here because neither this new committee nor the planning board is accountable to the general public directly. Mayor Mary Clare Higgins has stated publicly that she does not involve herself with nor is she responsible for decisions made by city agencies. Thus according to this logic the mayor is not accountable to the public for the decisions made by municipal committees, and the committee members themselves are not accountable to the public because they are appointed. While the city council will have to approve any zoning changes proposed, based on past performance it is highly probable that it will adopt the recommendations of this appointed committee because historically the council defers to department experts and its subcommittees when making policy.

The current proposal for the composition of the committee and the draft ordinance is available at Northassoc.org:

Membership is set to include:

"Three appointees shall have the technical skills and experience to address zoning, land use and planning issues.

Three appointees will represent broad based community interests (e.g. representatives of neighborhood, civic or housing related organizations)

One member representing environmental/conservation interests (e.g. Broad Brook Coalition, local Land Trust, Arcadia Wildlife Sanctuary)

One appointee representing economic development interests (e.g. Chamber of Commerce, Real Estate concerns, commercial or residential developers)

One member representing the Planning Board"

Under the present scenario the council will not necessarily play a formal role in the rezoning deliberations and there is no member of the council that I would classify as a zoning professional. In my view since three city councilors sit on the city’s best practices committee the council should consider including three of its members to sit on the as yet named rezoning committee so that they may represent the city’s constituents and participate in the deliberation of any proposals from the start. This would ensure public accountability from the get-go not just during the end game.

Moreover, while zoning and planning are valuable tools in creating a community template of land uses, they are and should be considered distinct fields from policy analysis. While there is some overlap between them, they are not synonymous with one another and the line between them should be somewhat clear. A complementary policy analysis should be an integral part of any zoning changes, that is to say, the committee should be forthcoming in discussing the costs and benefits of who might win and who might lose as a result of implementing any proposals.

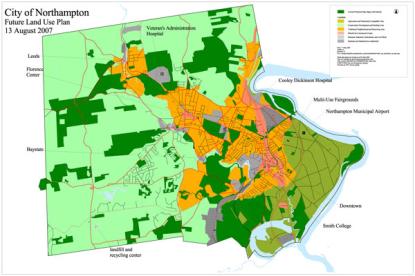

Why is this important? Because decisions made regarding zoning by definition will impact property uses and values in the city for years. For example, the city has undergone several zoning changes in the last decade. Among them, Northampton now has big-box retail ordinances on King Street, an educational use overlay district for Smith College, a water supply protection district in the area surrounding the landfill, restrictive zoning in the meadows section of the city by the Connecticut River, smart growth zoning on Hospital Hill, new wetlands regulations around the city, an expanded central business architecture district, and more permissive zoning in the built up areas of the city with an eye towards promoting infill development. To my knowledge no information has been made public with regards to quantification of how these various changes impact land values and several of the changes may arguably be considered regulatory takings.

For instance Northampton did not enact the water supply protection district in Ward 6 until the state required it as a condition of expanding the landfill. People who own property in that vicinity now have to live with more restrictive zoning and larger lot sizes so that the city can continue its regional waste collections. If the city does not expand the landfill it can be argued that the zoning was a regulatory taking as the state did not require the implementation of such a district prior. In addition, it seems presumptuous that the city would enact the water supply protection district before the issue of landfill expansion has been decided one way or the other. If the city does not expand the landfill will that district be dissolved?

According to Grady Gammage, Jr., a zoning, land use and real estate attorney in Arizona, "Zoning and land-use regulation is undertaken through a completely separate power of government known as the police power. Police power is the power to regulate society for the benefit of the health, safety, and welfare of the citizenry. It is the broadest and most general power of government, under which we establish police and fire departments, enforce building and health codes, and engage in all manner of general government regulation. Regulating the individual use of land by "zoning," or designating on a map what uses are appropriate in a particular area, was recognized as a legitimate use of the police power by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1926 in Village of Euclid vs. Ambler Realty Company."

Gammage goes on, "A regulatory taking is not about the physical seizure of property by the government. It is not, therefore, strictly speaking, the exercise of eminent domain. Rather, regulatory takings operate as a check or limit on the extent to which the police power can be used to regulate property." He further adds, "Note, for example, that if a regulation specifically allows physical invasion of property by the government, compensation is always due. We also know that if government regulation wipes out virtually all of the value of a piece of property, such regulation "goes too far" and compensation will be called for. If a regulation prohibits any use of property, even temporarily, compensation is required. But apart from those relatively clear cut or "per se" taking situations, it is hard to figure out when compensation must be paid. Courts must engage in a balancing test, weighing the impact on a private property owner with the purported need for the government regulation. In doing so they must be particularly mindful of an individual property owner’s "investment backed expectations" in acquiring a piece of property."

According to Gammage, in 2006 voters in the state of Arizona overwhelmingly approved a controversial act known as Proposition 207, the Arizona Private Property Rights Protection Act, by a margin of 65%-35%. It states: "If the existing rights to use, divide, sell or possess private real property are reduced by the enactment of applicability of any land-use law enacted after the date the property is transferred to the owner and such action reduces the fair market value of the property, the owner is entitled to just compensation from this State or the political subdivision of this State that enacted the land-use law." Supported by a New York libertarian named Howard Rich to the tune of $1 million, 207 was opposed by city and town officials across the state as well as by the state’s real estate development industry and has brought with it unintended consequences that have effectively frozen zoning changes in Arizona, even those that might be deemed desirable. It’s enactment happened because the electorate felt officials were going too far in their use of eminent domain, and that they wouldn’t stop short of a legislative directive. (Complete report available at: http://www.aztownhall.org/pdf/complete_91st_report_final.pdf 28 MB, see Chapter 4, pp. 41-50 for Gammage’s analysis.) The current effort in Massachusetts to eliminate the state income tax is another example of what a motivated electorate can do if it feels government is out of line and I hope that local officials take note-it doesn’t have to be this way.

In Northampton the water supply protection district was needed for the city to expand the landfill over a Zone II water protection area. As well, the meadows plan protects the Connecticut River flood plain in Wards 3 and 4 from development. Now that the other zoning changes mentioned above have been implemented, if they were to be "downsized" or otherwise altered to become more restrictive, property owners could claim that those changes amounted to a regulatory taking and seek compensation from the city, though the courts have generally upheld these downsizings without compensation according to Gammage. Nonetheless, if the city downsized the educational use overlay district it is quite likely that Smith College, with its ample financial resources, could lock the city up in court for years.

Clearly once new zoning is enacted it is difficult to change. In my view any rezoning of the city should not only consider the highest and best uses of the land but should also consider the policy ramifications that will be felt for years to come by Northampton property owners and residents. Who will win, who will lose and who should get to decide?