Hamlet 2 (2 1/2 stars)

Directed by Andy Fleming. Written by Andrew Fleming and Pam Brady. Starring Steve Coogan, Catherine Keener, Joseph Julian Soria, Amy Poehler, David Arquette, and Elizabeth Shue. (R)

British comedian Steve Coogan, whose long-running satirical turn as television personality Alan Partridge has made him one of his country's biggest stars, is somewhat less well known on this side of the drink. Audiences—or perhaps more likely, directors—don't quite seem to know what to make of his particular brand of comedy; his work stateside is a mish-mash of voiceover work and roles in the sort of indie films that more people will read about in the Sunday New York Times than will ever go to see.

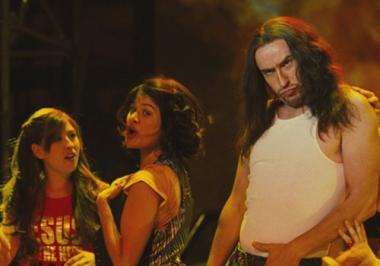

Hamlet 2, on the other hand, is an attempt to bring Coogan to the masses. As directed by veteran hack Andy Fleming (who also co-wrote the screenplay), it's a misguided one. Full of stereotyped roles, devoid of surprise, and rarely more than mildly amusing, the film shoehorns Coogan into an all-American story of wish fulfillment (the "let's put on a show!" that is the modus operandi of movie musicals) that all but strangles the actor's best qualities.

Coogan is Dana Marschz, a failure as an actor and not much better as the New Age drama teacher of a Tucson high school. Most of his productions are adaptations of Hollywood fare like Erin Brockovich, none of which get much respect from local reviewer Noah Sapperstein. That the reviewer is a diminutive kid who cuts off a conversation by explaining, "I have to go to recess now," doesn't keep him from name-dropping Roland Barthes in his column for the school paper. Sapperstein is well played by Shea Pepe; amazingly, it seems to be his first credited role, but he's sure to turn up in any number of smart comedies in the coming years.

Marschz's drama class is thrown into an uproar by the arrival of "the ethnics," a group of largely Latino students bused in from a nearby school. Just how out-of-touch (or lazy) the writers are is made clear by how they disrupt class: one student is actually carrying a boom box as though it were still 1987, and the rest throw crumpled balls of paper as if it were still 1953.

They aren't there long before drama class is canceled in the face of budget cuts, and Marschz, hoping to create a groundswell of support for the program, comes up with the idea that he hopes will save his job: a sequel to Hamlet. "Doesn't everyone die at the end of the first one?" asks his wife Brie (Catherine Keener). The solution to that small problem involves a time machine and cameo appearances from the likes of Jesus and Alfred Einstein. In truth, the play is less a sequel than Marschz's attempt to exorcise the demons of his childhood, which results in musical numbers like "Raped in the Face."

Once the community gets wind of the dramatic content, they try to shut down the production, which gets ACLU rep Cricket Feldstein (Amy Poehler, swearing a blue streak) involved and turns the play into a cause celebre. All too predictably, the students rally to save the show they hated weeks before; there are a lot of speeches about not giving up and taking a stand for what you believe in, but it all rings hollow. The film wants to have it both ways: to at once turn an ironic eye on the high school comedy and to be that very comedy. That it refuses to do one or the other is its fatal flaw.

There are some good points—Coogan holds the screen, and still has a certain electricity if you can block out what's going on around him, and Keener is full of her usual off-kilter charm until her character disappears. Elizabeth Shue, who once showed so much promise in Leaving Las Vegas, shows up here as herself, sort of, playing an actress named Elizabeth Shue who left Hollywood to become a nurse but still misses the make-out scenes.

But in a film whose biggest running joke is about a mute girl getting hit in the face—the other is about roller skating accidents—a few sparks aren't enough to keep the fire burning. The tragedy of Hamlet 2 isn't in what's on the screen, but what's not; we're still waiting for Coogan to break through.

Traitor (3 1/2 stars)

Written and directed by Jeffrey Nachmanoff. With Don Cheadle, Guy Pearce, Sa?d Taghmaoui, Neal McDonough, Archie Panjabi, and Jeff Daniels. (PG-13)

The one-word title of Traitor is deceptively simple. Calling to mind a bottom-rung straight-to-DVD release, it seems to leave little to the imagination, and viewers would be forgiven for expecting the usual assemblage of exploding cars and black-clad commando teams skulking through the dark, their night-vision goggles glinting green in the gloom. Instead, we get an unexpectedly thoughtful film, one that raises a good many unanswered questions about the nature of struggle on levels large and small. (Fans of the other type of film, take note: stuff still blows up.)

A clue to the film's deeper intentions comes as the credits roll; though director Jeffrey Nachmanoff is credited with the screenplay, the original story is attributed to one Steve Martin. And yes, it turns out, it's that Steve Martin—the comedian still best known as a "wild and crazy guy." Martin's fans, however, will recognize the actor's quieter side—the one that finds an outlet writing novellas and articles for The New Yorker—in the film's nuanced take on the thorny subject of right and wrong in an age of asymmetrical warfare.

Don Cheadle stars here as Samir Horn—ex-Special Forces soldier, devout Muslim, and terrorism suspect. Horn is a Sudan-born expat living in Yemen and supplying terror cells with raw materials and the know-how he picked up during his military career and a stint with the mujahideen in Afghanistan. He pops up on the radar of FBI agent Roy Clayton (Memento's Guy Pearce) when one of his sales is raided and he ends up in a Yemeni prison, but before Clayton can delve deeper, Horn is sprung in a violent escape rigged by his terrorist friend Omar.

By the time their paths cross again, Horn has been implicated in the bombing of an American consulate in France that killed six people, and Clayton—like Horn, he's the son of a preacher, and feels a bond with his quarry—is beginning to realize that perhaps there's more to Horn's story than the evidence suggests. It seems that Horn is the deepest kind of undercover agent, one who operates far outside the Geneva Conventions, and would probably be disowned by the government if he were caught. But is he still? Or has he immersed himself in the world of terror so deeply that he's become a terrorist himself?

It's a question that not even his government handler Carter (Jeff Daniels) can fully answer, and one that goes back to the late-blooming ambiguity of the title. Is Horn a traitor to his country? To an Islam that proscribes killing? To his own sense of morality, built on the assassination of his father? Or are we as a country traitorous, justifying the deaths of innocents in the name of safety? When Carter argues for the latter, Samir responds, "You know who you sound like, right?"

Cheadle, who has done so much great work over the years in roles both big and small, is the perfect choice to play Samir; it's Cheadle's innate dignity and integrity that make the role so full, and so believable. At many points, Traitor becomes a sad film; as Samir's choices continue to add layers of tragedy to his life, he paradoxically has fewer and fewer people to turn to, until he's alone with his memories of death.

At the heart of the film, though, is not one actor, but two. It's the relationship of Samir and Omar that provides a platform for most of the movie's emotional conflict. Both men are Muslims raised in the West, men who dream in English and struggle to reconcile their beliefs with the world they live in. The fact that one is a terrorist while one is perhaps a pretender is more a sad twist of fate than deliberate choice; the two are far more alike than they are different. Sadly, my experience at the film's screening suggests we still have quite a way to go in understanding the sense of fraternity fostered by religion: when Omar, finally betrayed by Samir, cried out that he called him "brother," grown men filled the theater with guffaws.

In the end, the filmmakers have the last word. When Clayton tries to make amends at the end of their last meeting by offering the traditional Islamic expression "as-salaam alaikum," Samir responds in kind, but can't help correcting his counterpart, telling him, "You should begin the conversation with that."

Also this week: Adventurous filmgoers can take advantage of the Amherst Cinema Center's continuing support for experimental film by attending These Are the Jams, a two-hour collection of six films curated by local filmmaker Josh Weissbach. Weissbach, who works at the theater, is the 2008 Cary Grant Film Award winner; the honor is given to an undergraduate filmmaker each year to help support documentary filmmaking.

These Are the Jams embraces a wide range of work, including Buffalo Common, a look at life in North Dakota as the state's long-standing Minuteman 3 missile silos are decommissioned. Against the backdrop of the Cold War's end, a disparate group—farmers and activists, military men and demolition derby drivers—descend on the area, each faction trying to claim a place in history.

Also screening is Half Sister, an elegiac film by Abraham Ravett about the half-sister he never knew. Ravett was in his mid-20s when he discovered that his mother had been married decades earlier, only to lose her family—including her six-year old daughter Toncia—in the horror of Auschwitz. The resulting film is a blend of history and imagination, as Ravett ponders a life that should have been.

These Are the Jams screens Sunday, Sept. 14 at 7 p.m. Tickets are $5.

Jack Brown can be reached at cinemadope@gmail.com.