Who'd have thought that one of the hot-button issues facing Northampton these days would be—garbage, the stuff we think disappears after we throw it away? But the question of whether the city's landfill should be expanded in such a way that a part of it will overlie the Barnes Aquifer, a pristine area water source, has nearly torn the town apart this year. On the trail with her notebook has been landfill stalker Mary Serreze ("Trash Is Good," October 9, 2008) and along the way she's filled the notebook with jottings on such subjects as local waste stream reduction and the lives and times of players in the garbage and recycling industry.

Here Serreze backs away from the controversy's hot burners and releases two cooler cuttings from her journal, one with an eye to the future, the other with a glimpse of a past in which the solid waste disposal crisis in the nation and the Valley was not yet foreseen.

The Haymarket: A Recycling Culture

In 2007, the City Council in Seattle, Wash., led by President Richard Conlin, passed an ambitious zero waste program. The city hopes, by making "source separation" both easy and mandatory, to divert 70 percent of its waste from the landfill over the next few years. Municipal food waste composting is a key provision of this plan.

Could this happen in Northampton? One business owner is not waiting around to find out. Peter Simpson, proprietor of Northampton's ?ber-hip Haymarket Caf?, has set up a pilot project. His customers are now faced with two disposal bins: one for compostables and one for recyclables.

"Everything we produce at the caf? falls into one of those two categories," Simpson said. "We don't offer a traditional trash can. Sometimes people want to throw something away here that they've brought in from outside. They're not going to be able to do it here; we don't want to encourage it. Perhaps in some small way we can make people think."

Unwaxed cups, paper plates, wooden stirrers, napkins, food waste—these are compostable. Bottles, coffee lids, straws and plastic to-go containers are recyclable. When I visited, a barista was carting buckets full of carrot tops (the Haymarket does a brisk juice business) out back and down the iron stairway to where a husky 80-gallon roll-out cart, adorned with a big Compost label, had been placed by a local hauling business. The Haymarket fills nine or ten of these bins a week.

"We used to produce 15 or 16 bags of trash every day. Now we only produce one," explained Simpson. "Patrick Kennedy of Alternative Recycling Systems set this up for us. He takes the organics to a farm. We aren't saving any money at this point—in fact, we're paying extra for the service. We share that big yellow compacting dumpster in the back parking lot with neighboring businesses, and we pay the same for trash disposal whether we produce 15 bags or one…but in my mind, that's not the most important consideration."

Could this private-sector source-reduction initiative serve as a model for all the other restaurants in Northampton? Simpson expressed a cautious optimism: "I think that most restaurant owners in Northampton would be happy to participate. But there are problems that would have to be solved in making this work on a larger scale. The city regulates the placement of bins, for example; the Department of Public Works would have to be brought on board. I've had conversations with Patrick about how to handle the larger volumes, how to make the logistics work. I know he's thinking about it."

"So why are you doing this? What prompted you, at personal expense, to restructure your entire waste system at the caf??" I asked.

"Because it's the right thing to do," he said. "We can't keep on doing things the old way."

A Conversation with the Trash King

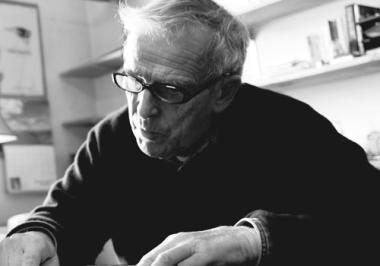

Armand "Buddy" Duseau is the undisputed don of trash in the Pioneer Valley, having been in the business for 61 years. The 72-year old Northampton native drives an impeccably maintained 1989 Mercedes and, on the day of our interview, was wearing a smart cashmere sweater with his khakis and sneakers.

Advocate: Thanks for coming by to talk.

Duseau: My policy is: get the truth out there and it might finally prevail over myth, half-truth and opinion… So, as the institutional memory of the business around here, I'm here to tell you about the history of the landfill.

I had these two partners at the time, and that was back in the '60s; one was a contractor, and the other guy's father sold cars. I asked them if they wanted to get in on this opportunity. They said sure, and each gave me 200 bucks. We went across the street to Bill Welch's office and had him draw up a contract. That was the beginning of Calduwood Enterprises—Callahan, Duseau, Wood, Cal-Du-Wood. The first thing we did was get into the trash business, which we bought from my father, who I'd been working for all along.

We expanded the business and needed a place to put the trash. The old burning dump on South Street was unacceptable. For one thing, plastics were entering the waste stream by then. It was right near what is the Arcadia nature preserve, black smoke bellowing. It couldn't continue. We secured that Glendale Road site for the landfill for a lot of reasons. It had everything we needed on site to build a road in—gravel and the like—and it had the proper soils for filtration.

I had a financial interest in this. I was hoping to do well. I'm not going to lie. So there was a battle. We're dealing with Mayor Puchalski, and at first he was against it. Enough said on that one. Also it was a residential zone up there, so there was a legal challenge. In court, we had to show that the landfill constituted a beneficial municipal use. You're going to benefit the community hugely, and the environment hugely, over what was there, was my thought.

We went to the local court, to the Land Court in Boston, and then to the [state] Supreme Court, and we won in all three places, based on their agreeing that the landfill provided an overwhelming public benefit. And when we get down to the final analysis, we said, as a business, the only sure way we are ever going to know that this is going to happen is if it is owned by the municipality.

Advocate: That what was going to happen?

Duseau: For the landfill to open and be running. We didn't want there to be any question. It could still be challenged based on the fact that it was owned by individuals instead of by the city. So we asked ourselves: would we give up private ownership, knowing what it would be worth to us for the opportunity to maybe operate it for a few years? We said yes. The city then took it by eminent domain and offered us $60,000. We had spent, what, $120,000 or $140,000 on the property, put in the roads. The whole thing ended up costing us about $200,000, so we had to take them to court. We finally got $210,000, which was fine. Then we had the contract to operate the landfill for $83,000, then $96,000 for a few years. There was no competition to bid, because nobody knew what a landfill was. This was the first landfill in the eastern United States.

Concurrent with opening the landfill, it was obvious to me that people should not have to run all the way up there with their trash. So I said, let's build a municipal transfer station. I talked to the city engineer. I said, you've got a lot of space here at the city barns, why not give this a try?

As each town was forced to build transfer stations by [the state Department of Environmental Protection], we constructed them. We were building them for $8,000, $9,000 and making a couple of grand. Then later, when the engineers got involved, they built the exact same facility, but they were charging $22,000 for them, and they wanted $10,000 for the engineering alone. But before that, we built 13 transfer stations.

Advocate: Calduwood Enterprises?

Duseau: Actually, Land Reclamation. That's the name of the legal entity that originally owned the landfill, and it was the name of the company that operated the landfill for three years or more. The same three guys. Land Reclamation alias Calduwood Enterprises.