Poetry's got a reputation to uphold, apparently—the reputation of that last brutal Himalayan peak in the dim haze of the academic distance. There have been plenty of attempts to make it seem friendlier, like the recent Poetry for Dummies. Add to those attempts the "slam poetry" movement, which all too often substitutes a theatrical firehose of passion for a necessary precision in communicative skill, and you get a terrible splatter of contradicting messages for those who would venture into poetic waters as readers or writers.

It's easy to argue that poetry could do with a broadening of audience and a lessening of the fear it induces in those who've been coerced into reading, with a forced and simplistic "symbolism" in mind, the bards whose rococo imaginings seem as attractively modern as a powdered wig and a snuff box. Yet too many attempts at lowering the fear factor sidestep an unavoidable truth at the heart of most revered poetry: the distilling of language to its essences produces strong stuff that isn't always easily quaffed. It's a learned behavior for most of us to read Wallace Stevens and get it. (And that, it turns out, is okay.) Pretending that reading and writing poetry is quick and easy does a disservice to the beautiful voyage of learning how to take in the whole broad scope of it, from the gut-level ease and dead-on rhythms of Langston Hughes to the esoteric word fortresses of T.S. Eliot.

Often, poetry demystification attempts address all poetry as equally interesting and valuable. But all poetry is not equally successful. That's okay, too—passing judgment on poetry may be a learned skill, too, but having opinions is nonetheless remarkably common. The important thing perhaps ought to be understanding the reasons for its success or failure.

So how is an aspiring poetry fan to scale the stony escarpment? Last year's Poetry Speaks Expanded book and CD set seems to have provided one very good answer. The original Poetry Speaks has been around for some time, and, of course, some of the audio has been around for a century or more. The newly expanded book is a daunting tome. Cracking it open is a revelation.

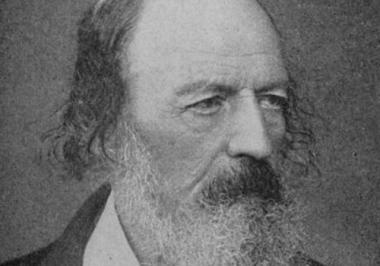

Part of poetry's retreat high among the peaks is easily explained: the written word has largely taken over from the spoken word, most especially in classrooms. That divide has only widened with the staking out of "spoken word artist" or "slam poet" territory as a counter to "academic poetry." It's widely accepted that poetry began as a storytelling medium, a repository for myths and stories of all kinds, delivered with meter and rhyme as memory aids for those who kept the epics; poems have, for a very long time, been more a script for performance than an end in themselves. But it's hard to realize that upon struggling through Spenser or Tennyson on the page as a first exposure to verse.

Poetry Speaks Expanded offers just the right antidote. The voices of the 47 poets included infuse the written words with the idiosyncratic passions that prompted their writing in the first place. They have a life that's hard to convey any other way. Poetry, in this fashion, becomes more accessible without being artificially dumbed down. It becomes lively, varied and sometimes conversational, despite its regimented contours on the page. Hearing such stuff may even help stem the tsunami of low-bar poetry flowing endlessly from the pens of poetasters, clearing up some of the contemporary poetic haze.

Hearing one of the greatest of writers, James Joyce, read from the remarkably inscrutable Finnegan's Wake (not technically a poem), makes the words go from a tangle to a song. The thickness of his Irish accent and his melodious tenor surprise, but reveal clarity and consistency in what looks at first to be longwinded nonsense. It's nothing short of revelatory, and offers an intuitive way in that years of struggling through annotations can't. Likewise, Gertrude Stein's words go from frustrating to pleasing, delivered with a confident grace that offers inflection and emphasis not necessarily apparent on the page.

On the other hand, the earliest recordings, made by Thomas Edison on wax cylinder, reveal highflown, almost comical reciting styles that make the poems of Tennyson and Browning seem like dusty relics—Poetry Speaks is not guaranteed to create new love affairs. Even Yeats delivered his poems, it turns out, in a melodramatic fashion that's equal parts spookiness and monotone thundering. Listen at your own risk.

If you love poetry already, these recordings are a must-have. If you don't, be careful: what seemed stilted and stuffy may well become melodious, even easy. And who knows where that could lead?