“Who you gonna believe, baby, me or yo’ lyin’ eyes?”

–Richard Pryor, on being caught in flagrante delicto by his wife.

Here’s how I lost my innocence about looking: I was teaching Social Studies to seventh graders at a Boston public middle school in 1974. I had just given my students a quiz on one of a series of Black History comic books which had been donated to the school by the Coca Cola Company. Gail Gousby approached my desk. “Here’s my test, Mr. Wright. What should I do now?” I suggested she draw a picture of Frederick Douglass, whose life had been the subject of the quiz.

Shortly thereafter, the bell rang and my students left for their next class. Going through the pile of papers on my desk, I come across Gail’s drawing, which had evidently been copied from a panel summing up Douglass’ life, an illustration of him from the waist up, with accomplishments listed underneath. She had, however, given her drawing a title of her own making. That title was: “Almost half of Frederick Douglass.”

Wow. Gail and I were both looking, but we were seeing very different things. Why, I wondered? Gail’s title was unquestionably correct, in some sense. But I–and other adults–had decided that this fact about what she had been looking at was irrelevant. But–and this was the most interesting thing to me, once it became irrelevant, it became invisible to me. So was seeing developmental, or cultural, or historical?

It made me think of a drawing of a bird in flight done by an Australian aboriginal artist I had seen earlier that year. Though the bird was “seen” in profile, its wings were drawn at equal length. From a “western” point of view, it displayed a ‘defective’ perspective. But as I was to learn, that view itself took centuries of argument to prevail. Plato would have agreed with the Aboriginal. He knew that birds’ wings were of equal length. Therefore, to draw them otherwise was a damnable lie. Plato hated the Greek artists of his own day, who were employing perspective, which meant foreshortening, which to Plato meant pandering to “the eye,” which lied. To Plato, Egyptian art, with its combination of profile and frontal perspectives, was truer.

Seeing, Gail had made me realize, is inseparable from thinking. And thinking involves a good deal of both construction and selective omission, which is to say, editing, which is what I have since come to do vocationally: I make documentary films, and teach media and visual literacy.

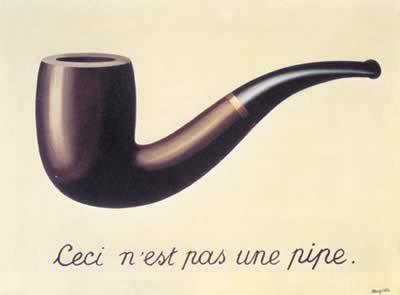

Nowadays, it strikes me that what both Gail and I were forgetting was that what we were looking at was absolutely not Frederick Douglass, not even a little bit of him. The Belgian surrealist artist Magritte drew it and then wrote it best:

Yes. This is not even close to being a pipe, no closer than Gail’s picture, both the “original” and her tracing of it, were to being Frederick Douglass. They are images, simulacra, whose relationship to the things in the world for which they are surrogates is actually quite tenuous.

Consider the sense information the Magritte “pipe” gives us. Take smell–either it smells like glass and dust, if you are viewing it on a computer screen, or it smells like paper and ink, if you have printed it out. Take touch–again, glass and dust, not wood, as your eye would lead you to believe. Taste? Again, not just no information, but false information. Hearing? We’ll give it a pass on this one. Finally, sight: amazingly, every part of this pipe is the same distance from our eye, though in our minds we know that the far side of an actual pipe bowl is further away from our eyes than the near side. And finally, this pipe’s context is simply a cream colored wash and it comes with text below it, unlike any actual pipe we might encounter in the world. And yet, most of us are able to construct an actual pipe from this odd mélange of false sense information.

I wonder, though, if this would be the case had we never seen an image before. Once, driving with a friend in Northern Italy in the early 1970’s, I got hopelessly lost in the Dolomites, and found myself at one point in the town square of a tiny mountain village, where two little girls peeked at us from behind a fountain. I had with me a little Polaroid camera which took black and white pictures. I beckoned to them and they approached the car shyly. One may have been seven, the other perhaps nine years old. While trying to converse with them in my wretched Italian, I took their picture, and when the image formed, I handed it to them. They looked at it, then shrieked in apparent terror and ran away. I think it very possible they had never before seen a photograph, although I will never know. But their reaction to this strange, black and white, two dimensional, simulacrum of themselves printed itself on me indelibly.

For the last few years I have been teaching a seminar in Visual Literacy at the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture. To prepare for it, I had to take a more systematic view of the subject. I also needed to bend it in an architectural direction.

Historically, the ideological privileging of the visual over all the other senses has been ongoing for several hundred years, though its origins can be traced all the way back to ancient Greece. The authority we give “vision” is by now deeply embedded in our language. “I see” means I understand. Great artists are “visionaries,” superior thinking is marked by “insight,” and so forth. Why? Technologies bend cultures, and the modern technologies of image creation and reproduction have profoundly influenced the way we see.

The most eloquent formulation of this situation is Guy Debord’s famous dictum that “all of modern life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that [used to be] directly lived has moved away into a representation.” The way we apprehend the world is now mediated by a flood of images: in advertising, movies, magazines, television, computer screens, PowerPoint presentations, etc. Increasingly, these visual images of the world come to stand in for the actual world and consequently tend to drive not just how we see our world but how we live in it.

Yet there has been in the twentieth century a philosophical counter narrative existing alongside the dominant one, which asserts that much of modern looking is inseparable from overlooking. Or as Martin Jay, in his survey of the French intellectual resistance to ocularcentrism puts it, “the alignment of the ‘I’ and the ‘eye’ emphasize the distancing of object from subject,” a separation of self from place.

Memory, for instance, is key to our deepest sense of place, but of all the senses, vision seems to me the weakest contributor to the retention of memory. When I try to recreate past places I have lived, smells, sounds and textures are more likely to trigger memories than sight. I forget what people look like long before I forget how they sound, for instance. That’s not so surprising. When you feel or taste or smell or hear, the world comes into you. Pure looking, by contrast, tends to hold the world at bay, to keep it outside ourselves. Why else would we so often close our eyes when we kiss someone we love?

Of all artists, it seems to me, architects ignore the senses other than visual at their peril. Good architects often look differently as well. When I was a boy, I used to spend summers at Taliesin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s community in Wisconsin. I remember one of his most experienced apprentices, John Ottenheimer, telling me he always took off his bottle-thick glasses to look at a new drawing of Wright’s. I thought he meant so he wouldn’t initially get bogged down by the details and could grasp the larger concept. Ever since, I have alternated squinting with more direct looking when I am seeing something memorable for the first time.

But perhaps John meant more. Recently, I have come across a remarkable essay called “The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses,” a piece by the Finnish architect and philosopher Juhani Pallasmaa. In it, he posits two kinds of looking:

“Peripheral [or ‘unfocused’] vision integrates us with space, while focused vision pushes us out of the space, making us mere spectators.”

The Pallasmaa essay is a protracted phenomenological attack on the dominant visual culture from many angles. He quotes Sartre, for instance, on the “medusa glance” [which] “petrifies” everything that it comes in contact with. In Sartre’s view, because sight is immediate, whereas the other senses operate over time, the effect of “ocularcentrism” is to replace time with space.

This reminded me, in turn, of Oliver Sack’s essay on the man who, blind since the age of five, miraculously recovered his ability to see in his fifties through an operation, with unexpectedly disastrous results. Before his operation he had known his beloved cat by the sense of touch, through stroking it, an act which unfolded over time, and which also yielded similar information each time. After the operation, he was completely undone by the fact that his cat in profile looked completely different from the way it looked when it was coming toward him, and that both these sights attacked his eye all at once. He could no longer recognize his cat from moment to moment. Space had replaced time, to disastrous effect.

In a way, something faintly analogous is happening to all of us as a result of the “unending rainfall of images,” in Italo Calvino’s phrase. We can see images of any thing, of any space, at any time. Space is temporalized, time is spatialized. But it is all flattened, two-dimensional. Much of it is stunning looking. It is candy for the eye. But is eye candy what we need to ground ourselves in the actual world? Pallasmaa posits that in architecture, we face as a result a “crisis in representation.”

Interestingly, just as I was thinking about this, an e-mail arrived from my old mentor John Ottenheimer, who has been a practicing architect in Seattle for many years. In it, he spoke about the relationship between plan and building.

“I have been drawing architecturally–to scale, etc.–since I was 9. I read plans as easily as most people read words. By the time I have finished drawing a plan of a building, I can close my eyes [italics added] and see the whole thing.” By contrast, he adds, “ I [have] found that most persons–including clients–when entering a new building don’t perceive the overall, the sense of space, the quality of the light, the scale, the proportions, the ‘fit’ to the human being moving thru the building. So they look at details, such as the doorknobs, the flooring material, the furniture, the light fixtures, etc.”

This thought echoes the words of Pallasmaa: “An architectural work [should not be] experienced as a collection of isolated visual pictures, but in it fully embodied material and spiritual presence.” Ottenheimer continues: “ I have come to the conclusion that architectural magazines are not about architecture, they are about photography. That is why architectural photography is such a specialty…the photographs are works of art in themselves….So now citizens mistake photographs for architecture.”

In response to this tyranny of the eye and the image, Pallasmaa calls for the “re-sensualization” of architecture, and points to contemporary architects who are doing so “through a strengthened sense of materiality and hapticity [touch], texture and weight, density of space and materialized light.”

A few years ago, my wife and I acquired a lovely piece of land and would like someday to build on it. But we’re still stuck in the muck of images, and my eye is the principal tool I possess to evaluate the drawn plans of our talented architect. It’s already difficult to imagine what the house for which he has drawn plans will look like in three dimensions, but to know what it will feel like to live in is exponentially more difficult. Because, as Pallasmaa truly says: “The ultimate meaning of any building is beyond architecture.”

Still, one must choose. And as Napoleon once said: On s’engage, et puis, on voit. “You commit yourself, and then you see.” And feel, and smell, and hear, and taste. So eventually, we will build. And when we do, and when the “drama of construction [is] silenced into matter, space and light,” I will ease myself into it in fear and trembling.