On a late June evening last year, staff and supporters of the YWCA of Western Massachusetts gathered at Springfield's Symphony Hall for a celebration marking the 140th anniversary of the organization, which defines its laudable mission as "the empowerment of women and girls and the elimination of racism."

Outside Symphony Hall that evening was another group of staffers and their supporters who maintain that, when it comes to its own employees, the YWCA falls short of its mission. They say the YWCA has, in fact, disempowered its front-line workers, the great majority of whom are women, many of them women of color. Five years earlier, employees had formed a labor union hoping to improve wages and benefits and address inequities they saw within the nonprofit. Their efforts, at that point, had met with more frustration than success.

For the union workers and their backers, the evening of the anniversary celebration was effective, to a point: they handed out leaflets and explained their position to many of the attendees, who paid $18.68 (a reference to the year of the Y's founding) to support the organization and hear a performance by Sweet Honey in the Rock, the renowned a cappella group whose music comes with a strong dose of social activism. Inside the concert, Sweet Honey's lead singer introduced one song with a call for a just resolution to the union's protracted contract negotiations.

More than six months later, resolution still hasn't come. The YWCA says it values its employees but, in tough economic times, simply doesn't have the resources to guarantee raises. The union dismisses this as double-speak, pointing to the large amounts the YWCA has spent both on anti-union efforts and on raises for top management. Recently, union members voted to authorize a possible strike if a contract can't be settled—an indication of how deep tensions run at an organization dedicated to helping some of the Valley's neediest residents.

*

In 2003, Kim Milberg was an outreach worker in a YWCA program that works with at-risk kids and young adults. Milberg had been at the Y since 1999, and over the years, she says, she had seen working conditions worsen at the organization. There was a lack of pay parity, she says, with employees who had similar experience and similar responsibilities sometimes making very dissimilar wages. Workers in the residential programs had concerns about scheduling policies. Low wages and benefits were leaving workers feeling unappreciated and contributing to high turnover, which affected the quality of services, Milberg says.

"We don't do this [work] to make big bucks. We want to make things better," Milberg said. But, she adds, when a person is anxious about her own basic financial security, it's going to affect her work: "How can you do your best [at work] if you have to choose whether to keep your lights on or take your daughter to the doctor?"

So Milberg contacted United Auto Workers Local 2322, which, despite its assembly-line-invoking name, represents more than 3,500 Western Massachusetts workers in the fields of education and health and human services. She also began contacting fellow employees at the YWCA's seven sites around the Valley, which include shelters for battered women, job-training programs, and programs for rape victims and teen parents. (According to figures provided by the union, starting salaries range from about $11 to $13 an hour for workers such as counselors, teachers, outreach workers, case managers and victim advocates, with project managers starting at $19.48.)

Talking to other Y employees, Milberg says, she realized they had many common concerns. She also realized that some were nervous that there would be backlash against an organizing campaign, since management made it clear it didn't want a union, she says.

By September of 2003, a majority of the roughly 55 YWCA workers eligible for the union had signed authorization cards seeking representation by UAW Local 2322. By law, at that point, an employer can choose to recognize the union and begin contract negotiations, or can force the union to hold an official union election, overseen by the National Labor Relations Board. The YWCA chose the latter route.

*

In a letter to James Shaw, then the president of Local 2322, YWCA Executive Director Mary Reardon Johnson explained that the organization would not recognize the union without a secret-ballot election for two reasons. First, the Y had doubts that UAW represented an "uncoerced majority" of employees. In an earlier letter sent to workers, Johnson wrote that some employees had complained to management of being visited at home by union organizers.

And, Johnson wrote to Shaw, "We believe that authorization cards are an inherently unreliable way of determining whether or not our employees want a union." (The proposed federal Employee Free Choice Act would allow workers to form unions simply by gathering a majority of signed authorization cards—a change, union backers say, that would prevent employers from running high-pressure, coercive anti-union campaigns in the weeks leading up to an election.)

In the case of the YWCA, Johnson sent employees a series of anti-union letters prior to the election. One letter, dated Sept. 29, explained that, "as we promised, management has been gathering information about Local 2322… and unions in general." Johnson noted that UAW's national membership was declining, and suggested the union was looking to bolster its numbers to increase its revenue. She also offered some financial figures, culled from Local 2322's 2002 financial reports, showing where the union spent its money, including $154,000 on its own employees' wages and benefits and another $67,000 sent to UAW's international office.

"All of this money comes from the 2 percent of wages Local 2322 members are required to pay in monthly dues or its initiation fees," Johnson wrote. "If it wins, Local 2322 will want all of you to join, pay dues or be fired!" she concluded.

A few days later, workers received another letter from Johnson, noting that even if the union vote succeeded, there was no guarantee that wages or benefits would increase. While a union would have the right to negotiate a contract with management, she wrote, "Bargaining is a two-way street. The employer can also make proposals. You could end up with more, the same or even less than you have now." And, she added, "It can take months or years to negotiate a first contract, if one is ever signed."

In another letter dated the same day, Johnson wrote, "There is another aspect of collective bargaining that you need to consider before deciding how to vote. You need to consider that if the parties cannot reach agreement at the bargaining table there could be a strike."

Johnson went on to note that UAW had called 16 strikes the previous year, "putting 104,177 employees out of work." Striking workers, she added, do not receive pay or health benefits or qualify for unemployment benefits. And, she added, "By law, an employer can permanently replace economic strikers."

Employees received two more letters from Johnson prior to the union vote. In one, she reminded them that even if they signed an authorization card, they were not obligated to vote for the union now. She also warned that, if workers later changed their minds, it's hard to get rid of an existing union. "You would be up against the United Autoworkers by yourselves," she wrote. "You could say that if the union wins you are stuck with it!"

Johnson capped her attempts to dissuade workers from organizing in an Oct. 10 letter. "I write to express my personal opinion that it would be bad for the YWCA to bring in the Autoworkers' Union," she wrote. "It would be divisive and force management and employee [sic] into two separate groups. I fear an 'us and them' mentality would develop. This goes against everything I believe in."

She continued, "The wedge of suspicion and accusations that has arisen during the past few weeks has been painful." Under her leadership, Johnson wrote, the Y had worked to meet the needs of employees and the community with limited financial resources; the organization was also committed to working with employees about concerns or problems.

Despite the dire outcomes Johnson warned could result, on Oct. 17, 2003 the workers voted 37 to 17 to form a union. And at least one of her predictions proved accurate: the first contract was a long time coming.

*

Contract negotiations began a few months after the union vote. Milberg was part of the negotiating team but was laid off the following summer, before an agreement was reached.

Milberg suspects her leadership role in the union efforts played a role in her layoff. "My relationship with management definitely became more difficult," she said. "We didn't keep it a secret who was organizing, and it wouldn't have taken anyone very long to guess."

At the time, Milberg was attending graduate school, working on a degree in social work. Prior to the union drive, she said, her manager had allowed her flexibility with her hours so she could balance work and classes; after the union vote, that changed. Milberg was told she could either accept the new conditions or take a layoff, she says. She chose the latter. "I did not choose to fight the layoff," she said. "Things were really uncomfortable there so I thought it was time to leave."

While "all sorts of factors" led to her layoff, Milberg said, "I don't think it would have happened had the organizing not happened."

Negotiations, meanwhile, dragged on for more than a year, with the two sides meeting as often as weekly. In early April of 2005—a year and a half after the union was voted in—the YWCA presented UAW with a final offer, which the union says included longevity bonuses for some workers and an overnight differential for employees in residential programs, but no overall wage increase. The union held a series of meetings to explain the offer to its members in preparation for a vote to accept or reject it. If they did not accept the deal, they could also vote to strike.

As the vote date approached, Johnson sent another letter to employees, urging them to accept the contract and warning them that "a strike or even the threat of a strike would not be good for you, your families or the clients who rely so much on us." Should the workers decide to strike, she added, the YWCA planned to continue offering services—apparently with non-union replacement workers. In a second letter, sent the day before the vote, she reminded workers that if they struck, they wouldn't qualify for unemployment benefits and would lose their employer-provided health benefits and, possibly, their jobs.

On April 20, the employees voted to accept the contract. Two weeks later, the two sides reached agreement on one lingering issue—a floating holiday won by the union—and the YWCA's attorney began to prepare a final version to be signed by union and Y representatives.

But on May 19, with the final contract agreed upon but still not signed, the YWCA informed the union it would not execute the contract—because, the organization said, it now had evidence that the majority of workers wanted out of the union.

That evidence was a collection of cards signed by 34 of the 64 members in the bargaining unit at the time. Each card stated that the signing member no longer wanted to be represented by UAW Local 2322 and "would like action to be taken to get them out of our agency, so we can get our voices back!"

At the time, Johnson—in response to a protest by the union outside the Y's newly opened facility on Clough Street—told the Springfield Republican that she was only responding to the apparent wish of the majority of employees. "When they said they wanted a union, we felt we had to listen. Now they're saying they don't want to be part of the union, and we feel we have to listen," Johnson told the newspaper.

She later expanded on that position in a letter sent to YWCA supporters. After having received the signed anti-union cards, she asked, "Should the YWCA have gone ahead and signed the contract with the union? Given the written evidence, we felt we could not."

Similarly, in a memo sent to YWCA employees in March of 2006, Johnson wrote, "The YWCA finds itself in this predicament because one year ago the majority of the bargaining unit told us they did not want the union to represent them any longer. We believed that legally and morally we had no other choice but to follow the stated desires of those employees."

Ron Patenaude, current president of Local 2322, says those cards were not a fair representation of what members felt. He maintains the cards were distributed and collected by a management-sympathetic employee on company time, with the knowledge of management—a violation of labor law, which forbids employers from getting involved in workers' efforts to decertify their union.

"I had people say to me, "I didn't know what to do. I'm approached; I'm told, "Sign this. If you've got any questions, go see your manager."' You're being told this at your desk at work. It was thoroughly intimidating," said Patenaude, who added that many union members remain reluctant to talk on the record for fear of repercussions.

Patenaude, however, pulls no punches when speaking on behalf of his members. "For Mary to say this was the will [of the union members] is horseshit," he said.

In the end, the contract was executed, after the National Labor Relations Board, in response to a charge filed by Local 2322, ruled in the union's favor in 2006. An order issued by David I. Goldman, an administrative law judge for the NLRB, found that the YWCA had only received the cards after it had agreed on and prepared a final version of the contract.

"Under longstanding Board law and policy, it is settled that once parties enter into an agreement—as the parties manifestly did here—a contract is formed and the employer cannot, without committing an unfair labor practice, refuse to execute the contract and unilaterally withdraw recognition based on a union's loss of majority support that did not occur until after the formation of the contract," Goldman wrote.

The judge ordered the YWCA to recognize the union and execute the contract. He also ordered the Y to post throughout its facilities a notice acknowledging that the organization had violated federal labor law, and affirming its commitment to recognize the union and the contract and not interfere with workers' rights to collective bargaining. While the YWCA appealed Goldman's decision, it was subsequently affirmed by Judge Michael Ponsor in U.S. District Court in Springfield, and later by a vote of the full NLRB.

In a recent interview with the Advocate, Johnson declined to discuss whether she felt the majority of employees today want to be part of the union. "All of that has been resolved," she said.

*

That issue might have been resolved, but labor/management relations at the YWCA remain unsettled. While that first contract was finally executed, it's since expired, sending the two sides back into yet another protracted and contentious round of negotiations.

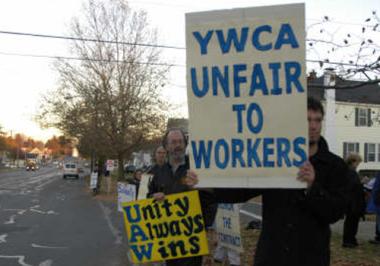

Last fall, union members voted to authorize a strike should an agreement not be reached. In December, employees and their supporters picketed outside the YWCA's holiday party. One sticking point, Patenaude says, is the Y's refusal to commit to raises for employees, other than a small increase in the overnight differential.

The Y's lowest-paid employees would also see a modest pay increase from a "salary reserve" fund, created by the state Legislature, that guarantees increases to human service workers making below a certain threshold (this year, a 2.57 adjustment for people earning less than $40,000). That money comes directly from the state and, Patenaude maintains, is intended to supplement pay increases from employers, not take their place.

According to Patenaude, the YWCA did offer to include a "wage re-opener," a promise that the agency would reopen the contract to consider pay raises should its financial status improve. Patenaude's not holding his breath for that, though. "These wage re-openers never work," he said.

Patenaude says he suspects the YWCA is trying to "starve" workers and drag out negotiations so long that employees become discouraged and give up on the union. "It's obscene," he said. "What they're trying to do is not give raises to the point that the membership is going to say, 'Why do we need the union?'"

Johnson told the Advocate that she couldn't discuss the specifics of contract negotiations, which are ongoing. But, she said, it "wouldn't be responsible" for the YWCA to commit to prescheduled raises years in advance, given the organization's fiscal realities.

The Y, Johnson said, gets 90 percent of its funding from government sources, plus United Way contributions. (The agency's most recent 990 form—an annual IRS document required of non-profits—showed that in 2006, the agency had a budget of $5.5 million, with $5.2 million of its revenue coming from government contracts.) In the current economy, she noted, neither of those funding sources can be counted on, and the Y wouldn't want to write into a contract raises that it might find it cannot fund down the road.

"The easiest thing to do would be to say, 'Sure, we're going to do X, Y, and Z.' That's the path of least resistance," she said. But, she added, "That's not righteous to me."

Patenaude, however, contends the YWCA does have the resources to reward its employees. He points to a review of the agency's financial records conducted by UAW's auditing department at its Detroit headquarters (the same department, he notes, that crunches the numbers of the big automakers). The audit found the Y had just under $600,000 in "unrestricted funds." It also found that it would cost the Y $48,000 annually to give the UAW members a 3 percent raise; that's less, Patenaude noted, than the Y has spent in recent years on anti-union efforts.

And, Patenaude adds, the YWCA has found the funds in recent years to offer raises to a number of top managers. According to the organization's tax records, Johnson's salary increased from $100,000 in fiscal year 2005 to $129,000 in fiscal 2007. Over the same period, Suzy Cieboter, the Y's CFO, saw her salary climb from $60,000 to $69,000. The YWCA's five next-highest paid employees—including program and department directors—earned salaries ranging from $50,000 to $64,000, according to its 2006 990 form.

Johnson declined to discuss her own and the other managers' pay increases. But Johnson did say it's misleading to suggest the agency is sitting on a pot of money that it could use for employee raises. While the Y does have some cash reserves—"Thank goodness," she said—that provides a necessary cushion that can be used, for instance, to pay employees while the agency is waiting to be reimbursed from a government contract.

In a September 2008 letter to YWCA staff, Johnson referred to the unrestricted cash reported in the union's audit as a misleading figure "plucked & off a financial report representing the difference between assets and liabilities over time." She also wrote, "Our wage and benefit program is already one of the best in Western Massachusetts for social service agencies. We intend to keep it that way."

While the contract did not include prescheduled raises, she added, "I would remind you that& employees got raises and holiday gifts each year."

This time, it's Patenaude accusing Johnson of offering misleading information. While some employees did get raises, he said, that money came not from the YWCA's largess, but rather from the state salary reserve fund.

*

Ultimately, Patenaude and Johnson both get back to the central issue of whether the YWCA values its employees, who do difficult, sometimes dangerous work for modest compensation.

In an interview, as in numerous internal memos and public statements, Johnson maintains the agency does—it just doesn't have the financial means to guarantee them raises in the future. "Does that mean our employees don't deserve them? Oh, no," she told the Advocate. "I believe they should be paid a lot more. … The money just isn't there."

Patenaude isn't buying that. Nor is he buying the notion that the YWCA respects and appreciates its workers. If it did, he asks, why would the organization insist it couldn't afford raises but still find the money to hire Skolar, Abbott and Presser, a Springfield law firm that's earned the enmity of the local labor movement for its work helping employers keep out unions? (In addition to its client work, the firm has hosted seminars with names like "Union Prevention: How to Stay Union Free.")

From fiscal 2004 to 2006, the YWCA's financial records show, the agency spent $161,000 on legal fees to that firm. "You don't hire Skolar, Abbott if you want to negotiate a contract. You hire them if you want to bust a union," said Patenaude, who noted that those legal fees would have more than covered a 3 percent raise for union members, according to UAW's audit.

Patenaude is now preparing to bring the YWCA's contract offer to the employees for a vote. He's also trying to call the attention of the public, and the agencies and lawmakers that provide funds to the Y, to what the union considers a grave misuse of public funds.

Asked if she thinks the union's public campaign—including pickets and its YWCA website—have hurt her agency, Johnson told the Advocate, "I think that folks have to look at outcomes. One just has to look at the work."

She continued, "What we're concerned about is that we be able to go forward and deliver services. And we have outstanding workers to do that."

Here she and Patenaude are in agreement. "Any greater good that's done [by the YWCA] is done by the workers—who can't get a fucking raise," Patenaude said.