It was late December. It was a Springfield City Council meeting about the controversial plan to redevelop the former Longhill Garden apartments into affordable housing. It was Councilor Bud Williams, criticizing the Sarno administration for failing to "do its due diligence" and find other options for the complex.

Three days later Williams was back, this time blaming Mayor Domenic Sarno for failing to enforce the city's $90 trash fee. A few weeks after that, and here he was again, now criticizing the mayor for his handling of a police complaint review board. Swift on the heels of that came a letter from Williams to Sarno and the city's Finance Review Board, chastising them "over the lack of action that you have failed to take relative to the City's budget and finances." (What the letter lacked in grammatical integrity it made up for in multiple-exclamation point enthusiasm: "Its [sic] imperative that action be taken now ! ! ! !")

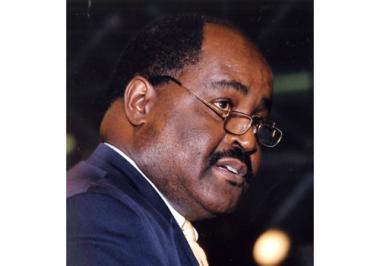

Such a sudden burst of legislative energy from Williams could only mean one thing: it's an election year. But this time, he's not just looking to hold on to the Council seat he's been warming for the past 15 years. After years of talking about it, Williams is finally taking a shot at the mayor's office—meaning Sarno better get used to the sniping.

*

Maybe that won't be too hard. After all, Sarno's first year as mayor has hardly been a ticker-tape parade.

After his surprise victory over Charlie Ryan in 2007, Sarno didn't get much of a honeymoon. First he backtracked on the big promise of his campaign, to rescind the widely despised trash fee instituted under Ryan. Next he alienated councilors who complained about the lack of openness from the mayor's office, most notably when Sarno tried to shut them out of the budget process.

Sarno's critics—chief among them Councilor Tim Rooke—have criticized him for failing to take strong, decisive action at a time when the city needs real leadership. Even when Sarno has made tough decisions—giving his nod to the Longhill Garden plan; canceling the city's tow contract after months of non-compliance by the vendor—the effect was diluted by the drawn-out deliberations he took to get there. In other cases, Sarno is still circling around tough decisions, like whether to take the former Mason Square library from the Urban League by eminent domain.

While Sarno maintains he loves the job of mayor, from the outside, at least, the mayor's office looks like a rather lonely place. None of Sarno's former colleagues on the Council has stepped forward as the sort of reliable backer previous mayors have been able to count on; instead, the councilors have generally treated him with ambivalence, at best, or, at worst, Rooke-intensity scorn.

Nor has Springfield's legislative delegation done the mayor many favors. Even as Sarno was pushing to extend the term on the city's $52 million state bailout loan—without it, the city government would have faced a repayment schedule it couldn't have met—local legislators were doing their best to embarrass him. State Rep. Ben Swan (a sometime foe, sometime ally of Williams') tried unsuccessfully to hold up the repayment bill unless the state agreed to intercede in Sarno's decision to cancel the city towing contract, which was held by a friend of Swan's. State Rep. Cheryl Coakley-Rivera, meanwhile, was able to cram into the bill a provision that would phase out the trash fee—a provision that some detractors say ultimately has no teeth, but that presumably earns Coakley-Rivera some points with her constituents.

Add to those headaches the many problems beyond his control, like the meltdown in the state's economy that has led to dramatic cuts in local aid, and Sarno is not exactly striding into this fall's election as a shoo-in.

*

But really, Bud Williams? The seven-term councilor, a retired probation officer, hardly screams out fresh, vital leadership.

Williams would bring at least one undeniably desirable change to the mayor's office: he'd be the first African-American to hold the job, no small achievement in a city where the majority of residents are black or Latino but the government is overwhelmingly white.

Still, it's important to remember that the notoriously flip-floppy Williams has been reliably unreliable on issues that have been particularly important to black and Hispanic residents, including ward representation and needle exchange. In 2005, when Williams was supposed to be monitoring a particularly contentious board election at the New North Citizens' Council, he enraged some residents by falling asleep. When questioned about his lack of attention by the Springfield Republican, Williams offered the inexplicable defense, "I dozed off, but I didn't sleep. There's a difference."

And, he added helpfully, "I've dozed off during City Council meetings."

When the Springfield Library and Museums Association decided to secretly sell the Mason Square library in 2003, Williams was among the so-called "leaders" of the city's black community whom David Starr—an SLMA bigwig and president of the Republican—met with to quietly inform them of the plan. Williams, the only member of the City Council who was told of the sale ahead of time, did not fight the deal, as other councilors did when the deal was finally made public. (When the city, under the Ryan administration, later sued the SLMA over the sale, Starr indicated in a deposition that it wasn't unusual for Williams to meet with the newspaper executive, whose ability to influence local politics notoriously reaches beyond the editorial page. "[U]sually [Williams] liked to meet at breakfast because it suited his schedule," Starr told then-City Solicitor Pat Markey.)

And let's not forget the years Williams spent as one of Mayor Mike Albano's go-to councilors. Albano's administration left the city with a staggering financial crisis and a legacy of corruption—a situation Springfield can't afford to repeat.