As the United States faces severe economic difficulties many Americans–myself included–are debating which public and private actions might best ward off even worse disaster. Yet at the risk of sounding Pollyanna-ish I want to suggest that a “positive” outcome of the current crisis might be a renewed national look at the very real challenges of living either in poverty or on its brink. Nope, I’m not speaking about CEOs who face the possibility of making a mere ½ million a year. They will be fine. I am speaking of the millions of Americans like those I lived and worked with in Kansas City, MO in the 1990s who face each day with a profound fear of where their children will sleep that night, how to acquire basic necessities like food and clothing, and how to navigate the competing demands of work, job searching, childcare, parenting, etc. If some good is to come of the current disaster we might do well to consider the ways in which American leaders and “average” citizens alike have understood and addressed poverty in the past because there is a direct relationship between ideas about what it means to be poor and our nation’s response to the spectre of poverty. At times over the past four centuries poverty has been celebrated and decried. It has been part of the national agenda and it has been relegated to families, special-interest groups and faith communities. It has been identified as the result of individual failing in some generations and as the result of community neglect in others. Here I am putting up for discussion some moments in the history of what I call the “making of poverty and its meaning” in the United States. Perhaps out of this mélange of essays, works of art, political journalism and laws, we might see a way forward.

A Model of Christian Charity: “in all times some must be rich, some poor…”

I don’t dislike John Winthrop’s famous 1630 speech (“A Model of Christian Charity”) but I dislike the fact that Americans tend to remember the “city on a hill” part more than the “Model of Christian Charity” part. Politicians love to quote Winthrop’s words about the new community settling Boston in the 17th c. being “as a city upon a hill”. Most Americans also know the second half of this sentence that speaks about the “eyes of all people” being “upon us”. But these catch phrases come at the end of a long document that lays out Winthrop’s larger message about the order of civil society and the place of the poor within it. The full text situates the reader/listener in a worldview dominated by 17th c. Christian understandings of social and spiritual hierarchy. In fact, most of the text is a primer on the ways in which Winthrop and his followers understood the need for the poor in their new adventure. When Winthrop called for the residents of Massachusetts Bay to obey God’s call to be “knit together” as one it was with an understanding that, “in all times some must be rich, some poor, some high and eminent in power and dignity; others mean and in submission.” This claim comes in the document’s first paragraph and it is followed by many reasons for this inequality including its role as a mirror of all of God’s creation and the idea that the poverty and suffering of some was necessary to ensure that the better off could carry out their Christian duties of charity. In Winthrop’s 17th c. worldview poverty was understood as part of God’s plan. But…so too was the requirement for the well off to help the others. Smack in the middle of his thesis Winthrop proclaims two rules which all who have worldly goods should live by: “First, that every man afford his help to another in every want or distress [and] Secondly, that he perform this out of the same affection which makes him careful of his own goods…whatsoever ye would that men should do to you.”

The “vendu” system and the emergence of poverty as an individual moral failing

So from the early years of Anglo settlement in Massachusetts local communities were understood to be ultimately responsible for those who found themselves in difficult circumstances. Given death rates, gender-based limits on work, and the large number of births in average families in the late 17th and 18th centuries, it is not surprising that a majority of the poor and dependent of this era were women and children. To address this fact and “care” for the poor, until the early 1800s towns in Massachusetts often auctioned dependent citizens off to other residents—the lowest bid won. This “vendue” system (after the French word for “to sell”) meant that towns paid the “buyer” to provide food, clothing, and housing for those they took in. While there was certainly the possibility of abuse and neglect, the system worked in large part because until the early 1800s there existed a sense that the poor deserved help from their fellow citizens. Yet by the early 1800s this sentiment had shifted. Distinctions between the “deserving” and “undeserving” poor cropped up and Americans increasingly began to understand poverty and dependence as the result of personal failings. In this view the poor were morally deficient and/or lazy and as such both public and private support for them began to wane. The 19th century approach to the poor was marked most notably by the rise of publicly funded almshouses and poor farms, institutions organized much like prisons.

Writers and Artists Take Up the Cause: Literary Naturalism & Photojournalism

As the 19th c wore on, increasing urban poverty spurred on by the influx of both rural migrants and immigrants from around the world led some social reformers to question the nation’s punitive approach to poverty. Yet for as long as Americans saw “the poor” as individually deficient and responsible for their own suffering, it would be hard to convince Americans to care about their plight. When Stephen Crane’s Maggie: A Girl of the Streets was published in 1893 (followed by Dreiser’s Sister Carrie in 1900) literary and policy trends aligned. These works of literary naturalism turned readers’ eyes toward the dirty and difficult lives of Americans trying to make their way in the world of sweatshops, meat packing plants and urban tenements without any safety net. In a critical new move, these novels presented poverty and economic failure as the result of external circumstances, not of individual moral failings or lack of effort. Poor Americans were depicted as part of a larger poverty-stricken environment. Dirty flats and unsafe workplaces destroyed lives, character, and potential for success. Poverty caught the poor in its clutches and no amount of individual effort brought escape. Literary naturalism put forth the notion that unseemly social problems (out-of-wedlock pregnancy, illegal activities) could be eradicated if poverty (the condition that encouraged them) could itself be controlled. In many ways legislative efforts at the turn of the 20th c. regarding sanitation, education reform, building codes and workplace safety promoted similar views. Social reformers and politicians were assisted not only by novelists, but by the growing ranks of photo journalists using cameras to record and interpret the effects of poverty on both individuals and society. Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine were two the most influential of this group.

Yet, this new understanding of the meaning of poverty and the plight of the poor did not immediately translate into a large-scale public response. The poor in the early years of the 20th c. were just as likely to turn to private service providers (the settlement house movement, for example) or fraternal organizations tied to ethnic or racial identity as to government. African Americans and various immigrant groups established fraternal organizations and even financial institutions to aid one another in times of death, loss of work or illness.

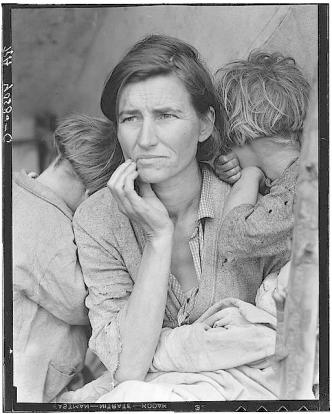

Poverty Looks like “us”: The Farm Security Administration Photographs of the 1930s

But it would take the crisis of the 1930s to convince Americans (on a large scale) of the critical role of the federal government in both causing and alleviating poverty and its threat. If the Great Depression forced average middle-class Americans to face the narrow line between self-sufficiency and poverty and dependence, some New Deal programs helped to make poverty visible and convince Americans that there was a role for the federal government in its eradication. Perhaps no such program did this more effectively than the Farm Security Administration’s (FSA) photography project, which sent photographers across the US to record the Depression’s impact on Americans. The images were then circulated to encourage support for New Deal innovations and spending. The most iconic of these “faces of poverty” is known as “Migrant Mother,” Dorothea Lange’s Madonna-and-child like image of a woman and her children impacted by the Depression. A face of “poverty” that looked so much like those of middle-class white America was a powerful tool for garnering support for FDR’s programs.

But it would take the crisis of the 1930s to convince Americans (on a large scale) of the critical role of the federal government in both causing and alleviating poverty and its threat. If the Great Depression forced average middle-class Americans to face the narrow line between self-sufficiency and poverty and dependence, some New Deal programs helped to make poverty visible and convince Americans that there was a role for the federal government in its eradication. Perhaps no such program did this more effectively than the Farm Security Administration’s (FSA) photography project, which sent photographers across the US to record the Depression’s impact on Americans. The images were then circulated to encourage support for New Deal innovations and spending. The most iconic of these “faces of poverty” is known as “Migrant Mother,” Dorothea Lange’s Madonna-and-child like image of a woman and her children impacted by the Depression. A face of “poverty” that looked so much like those of middle-class white America was a powerful tool for garnering support for FDR’s programs.

Michael Harrington’s The Other America and Beyond

As long asmainstream, middle-class, white Americans (and their elected officials) could “see” themselves in “the poor” there was hope for sustaining programs to help the latter. Unfortunately, by the 1960s the relative prosperity of most Americans and the safety nets put in place in the 1930s seemed to make it increasingly hard to recognize poverty unless you went looking for it. This was the finding of Michael Harrington whose acclaimed study The Other America: Poverty in the United States forced academics, policy makers, and Washington insiders to consider that much poverty was “hidden” in the US because “the poor” did not look like the poor of the past. After all, few poverty-stricken Americans in the Cold War era wore rags, stood in soup lines, or lived in hovels. Furthermore,numerous Americans were members of the working poor, individuals employed at low wage jobs with no benefits…living paycheck to paycheck. It was easier and easier, argued Harrington, for Americans to imagine that poverty did not exist. And if poverty did not exist then how could it be alleviated? The Kennedy and Johnson administrations took Harrington’s claims to heart: Medicaid, Medicare, food stamps and other Great Society programs of the 1960s were one direct response.

And yet, despite new approaches to poverty, by the 1990s journalist Barabara Ehrenreich had no trouble finding the working poor struggling everywhere throughout the United States when she went undercover to write: Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America. When I first read Ehrenreich’s book I was not shocked since I had seen much of what she wrote of firsthand in my first career as a social worker. But her findings are sobering. For example: 1) We live in a nation where working mothers and children live in hotels because they do not have both first and last month’s rent up front for an apartment; 2) We live in a nation where working 40 hours a week at minimum wage means living on the edge of poverty.

In the past few years what has become most troubling to me is that we live in a nation where ideas about who the poor are, what they look like, and what “causes” their poverty seem to be harkening back to earlier eras. In fact, as recently as 2007 during a Congressional Debate about raising the minimum wage, US Congressman Jack Kingston (R-GA) suggested that little more than being married and being willing to work longer hours would go far to get many people out of poverty. Echoes of “it is your fault” ring loudly in this rhetoric. Yet in this case the logic does not add up. According to the US Dept. of Human Services’ own calculations as of today (Feb. 2009) a single worker working full time (40 hours/week) 50 weeks a year at the federal minimum wage ($6.55/hr) makes $13,100/year pre-tax. This number falls below 125% of the federal poverty level thereby making him/her eligible for most federal assistance programs. If that same worker has a dependent, and works 52 weeks a year (no time off) he or she is eligible for all federal assistance, since the “100%” poverty level for a two-person household is $14,570/year. These numbers fly in the face of the idea that hard work leads to security.

ideas about who the poor are, what they look like, and what “causes” their poverty seem to be harkening back to earlier eras. In fact, as recently as 2007 during a Congressional Debate about raising the minimum wage, US Congressman Jack Kingston (R-GA) suggested that little more than being married and being willing to work longer hours would go far to get many people out of poverty. Echoes of “it is your fault” ring loudly in this rhetoric. Yet in this case the logic does not add up. According to the US Dept. of Human Services’ own calculations as of today (Feb. 2009) a single worker working full time (40 hours/week) 50 weeks a year at the federal minimum wage ($6.55/hr) makes $13,100/year pre-tax. This number falls below 125% of the federal poverty level thereby making him/her eligible for most federal assistance programs. If that same worker has a dependent, and works 52 weeks a year (no time off) he or she is eligible for all federal assistance, since the “100%” poverty level for a two-person household is $14,570/year. These numbers fly in the face of the idea that hard work leads to security.

In my most cynical moments of late I have thought (and at times said to others) that our nation’s recent swift federal support for those impacted in 2008-9 has more to do with powerful Americans imagining themselves to be “poor” than any consideration of those who have filled the same ranks for the past decades. Yet I remain guardedly optimistic. As I listen to the debates and diatribes about our current economic crisis, I can’t help but hope that as more and more policy makers imagine themselves (no matter how hard they work or what their marital status is) as potentially part of America’s “poor,” we might begin to have some soul-searching debates about the meaning of poverty and the needs of the poor in a nation which has both an abundance of resources and an increasing abundance of dire need.

<!–[if !supportEmptyParas]–><!–[endif]–>