This year's election season promises to be a lively one, even by Springfield standards. First-term mayor Domenic Sarno—whose upset victory over predecessor Charlie Ryan has been followed by 16 rocky months, punctuated by political disputes, drastic reductions in state aid, and impending layoffs of city workers—could be facing challenges from multiple contenders; among the names kicked around as potential mayoral candidates are city councilors Bruce Stebbins and Bud Williams, as well as Brian Corridan, owner of a Springfield investment firm.

Meanwhile, the long-overdue implementation of ward representation on the City Council means that body will see some welcomed new faces as a number of established neighborhood activists line up to take a shot at the eight new ward seats. The sitting councilors, meanwhile, will be left to scramble for the remaining at-large seats (which will be reduced from nine to five), run for a ward seat, or step aside.

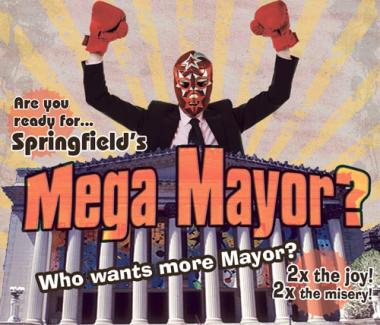

But overshadowed by all the electoral intrigue, so far, is another important question, one that could have a profound effect on how Springfield is governed for years to come. On the November ballot, voters will weigh in on a binding ballot question asking whether the city should extend the current two-year mayoral term to four years, beginning with the 2011 election. Proponents say the change would allow the mayor to get more done, and might even attract a stronger pool of candidates for the job.

While the move to extend the mayoral term has strong backers, particularly in the city's business community, there's yet to be much public debate on the issue. Perhaps that's because the ballot question didn't originate with the public, but rather with Springfield's Chamber of Commerce, which lobbied hard to get the question included in a bill, passed in January, that extended the city's repayment schedule on a $52 million state loan. The bill also created a chief administrative and financial officer who will report to the mayor but will be in charge of city finances.

While the loan extension was widely applauded, the additional provisions, including the ballot question, were not embraced by all local politicians and residents. Some contend that significant electoral change should originate with the city's electorate, not its business leaders, many of whom live outside Springfield. Others resented having the term question and the financial officer position tied into the repayment extension, which the city desperately needed to avoid a complete fiscal meltdown. But proponents say those elements of the bill are vital steps to securing economic and political stability in the city during unstable times.

*

The ballot question was included in the so-called "Springfield bill," which gives the city 15 years to pay off the $52 million, zero-interest loan it received from the state in 2004, as it struggled to recover from the financial mismanagement and corruption of the Albano administration.

The loan was part of a bailout package that also included the creation of a Finance Control Board to oversee the city budget, and was generally regarded as a last-ditch measure, just short of the state putting Springfield into receivership. Prior to the bill's passage, the city was expected to pay back the loan in five years, with the first payment due this year—an expectation that, even with the stability achieved under the Control Board and the Ryan administration, it appeared unable to meet.

While the term extension question ended up as a key component of the bill, its origin predates the bill, said Jeffrey Ciuffreda, vice president for government affairs for the Affiliated Chambers of Commerce of Greater Springfield, the regional umbrella group that includes the Springfield chamber.

A couple of years ago, Ciuffreda said, a group of local businesspeople began talking about what they could do to help the city prepare for the exit of the Control Board, which will leave this summer after five years in place. "We were an advocate, obviously, of returning Springfield to its own control, and wanted to make sure [the city was] ready for it," he said.

The Chamber formed a Governance Study Committee, which developed a number of suggestions members felt would create long-term financial stability for the city by ensuring some continuity from one administration to the next. To address that point most directly, the chamber suggested creating the chief administrative and financial officer position. The CAFO position made it into the final bill; city officials are currently interviewing applicants for the job.

The group also concluded that the mayor's term should be lengthened. "Having a chief executive of a city the size of Springfield being in office only two years simply was not effective," Victor Woolridge, president of the Springfield Chamber and a managing director at MassMutual's Babson Capital Management, told the Advocate. "It was counterintuitive and counterproductive in terms of the long-term planning and management of the city." Four-year terms would allow mayors time to plan strategically and to implement longer-term projects "without having to look over their shoulders" at would-be rivals eager to unseat them, he said.

A longer term could also address a problem that too often plagues Springfield: a lack of consistent follow-through on big developments and other major projects, which can take years to come to fruition. More continuity in City Hall could help keep the focus on these projects, Ciuffreda said. "Sometimes people would say we were trying to run [the city] more like a business," he said. "That wasn't necessarily true. We just wanted to introduce some business practices."

The Chamber committee also supported raising the mayor's salary from the current $95,000 a year to $150,000. The group tried to get included in the bill a study to compare Springfield's salary with that paid to mayors in other cities, but the study did not make it into the final version of the bill.

"I understand, certainly, in these economic times that can be a much more difficult question," Woolridge said of the proposed raise. "But I still think it's an appropriate question, and an important one." Right now, he noted, the mayor earns less than a number of city employees (including the school superintendent, police and fire chiefs and other department heads) despite being the chief executive, in charge of a half-billion dollar budget, among other major responsibilities.

"It's in the best, long-term interest of the city to pay the mayor an appropriate salary for managing a budget of this size," Woolridge said. By making the salary more competitive with the private sector, "you can broaden the audience of the people who will run for mayor. Expanding the talent pool would benefit the whole area."

To City Councilor Tim Rooke, who worked with the Chamber committee that proposed the term extension, there's no question that a four-year term would result in better, stronger leadership. "Two years is completely ineffective as mayor, where you have to make difficult decisions every day," he said. "You really need four years to get things done."

Like other supporters of the extension, Rooke believes that a two-year term leaves a mayor in continual campaign mode, and can make him or her wary of taking politically unpopular positions.

"You do your work for the first year, and the second year you're busy campaigning, trying to get elected. … And every decision you make you think, 'I hope I didn't piss off this guy or that guy,'" Rooke said. "That is always in the back of any mayor's mind. I think it would be difficult to disagree with the logic that that prevents you from always making the best decision. Because a lot of elected officials are self-serving—they want to get re-elected, not move [the city] forward….

"I think a four-year term would be a logical choice, to allow for the natural decision-making process to take place, where you're making decisions for what's best for the city, and not what's best for you politically," Rooke continued. "It would insulate the mayor, whoever he or she would be. Knowing you're there for four years, you have plenty of time to implement your plan for the city."

That sort of thinking has prompted several other Massachusetts cities to extend their mayoral terms in recent years. Over the past decade, Lynn, Malden, Salem and Revere all switched from two-year to four-year terms. According to the Mass. Municipal Association and the state Elections Division, the mayors of Boston, Brockton, Lawrence, Melrose, Newton, Waltham and Weymouth also serve four-year terms; Greenfield's mayor serves three years, an anomaly in the state. There's also been talk of moving to a four-year term in Chicopee, where in 2007 voters approved a non-binding ballot question.

Not all cities with longer terms are happy with that structure, however. To some, a two-year term makes a mayor more immediately accountable, aware that he or she can be quickly unseated by dissatisfied voters. In Revere—which enacted a four-year mayoral term in 2004—there's been a movement underway to cut the term back to two years; according to the Boston Globe, the push appears to come from business owners displeased by Mayor Thomas Ambrosino's support for moving the cutoff time when bars have to stop serving liquor from 2 a.m. to 1 a.m.

Longer terms can also allow an incumbent more time to solidify power and build up his or her war chest. That's a legitimate concern in a city like Springfield, where typically low voter turnout and a certain apathy about government can often mean that a bad mayor (or city councilor, or School Committee member) can hold on to his or her seat much longer than deserved.

How voters feel about the length of their city's mayoral term may have a lot to do with how they feel about their sitting mayor. A four-year term can be a blessing with a good mayor, and an eternity if the mayor turns out to be a bum.

"That's the risk—the general public could elect a bum any time," Rooke said. But with a term that's long enough to allow real accomplishments, and a salary that's competitive with what an able leader could earn in the private sector, he added, "you would probably attract someone who is not motivated by politics, but is motivated by helping the city."

*

While there's yet to be much debate about the merits of the term extension question, there have been complaints about how the question ended up on to the ballot, along with other provisions of the Springfield bill. Indeed, for a time, the bill was so mired down in political bickering that it looked as if it might not pass at all.

Gov. Deval Patrick submitted the bill last summer to the Legislature, which then sat on it for months. With the end of the legislative session approaching—and the date for Springfield to make its first loan payment nearing—lawmakers finally passed the bill in January, on the final day of the session. It was a hard-won victory, featuring an embarrassing power struggle between Mayor Domenic Sarno, who was eager to see the loan extension granted, and several members of the Springfield delegation.

State Rep. Ben Swan, for example, threatened to kill the bill unless state officials agreed to look into Sarno's decision to terminate a city towing contract held by a friend and campaign supporter of Swan's. Rep. Cheryl Coakley-Rivera, meanwhile, insisted that the bill include language that would abolish the controversial $90 residential trash fee created under the Ryan administration. Sarno had campaigned against Ryan on a promise to rescind that fee, but dropped that plan once he got into office. While Coakley-Rivera's language got into the bill, it remains to be seen whether the fee will actually be abolished.

After months of languishing in the Statehouse, the eleventh-hour passage of the bill, amid much political wrangling and anxiety, struck some observers as a rush job. With city officials warning that the city would face financial ruin if the loan extension weren't granted in time, an air of desperation hung over the process, and not much attention was paid to the term extension question.

At a hearing on the bill last summer, Coakley-Rivera argued that a local ballot question should come from the public, not the governor. (By the time of the bill's passage, Coakley-Rivera saw no problem attaching her own condition—the language to abolish the trash fee—to the law.)

School Committee member Antoinette Pepe, meanwhile, objected to the loan extension being tied to the additional changes included in the bill. "We are actually almost held hostage by the language here," Pepe was quoted as saying in the Springfield Republican last year.

Michaelann Bewsee, a cofounder of Arise for Social Justice, knows firsthand the challenges of trying to change Springfield's governmental structure. She and fellow activists spent more than a decade fighting to bring ward representation to the City Council. Bewsee says she has "mixed feelings" about a four-year term, but ultimately sees some benefits to the proposal. "You get a chance to really get your feet under you, and get policy in place and implement that," she said. Of course, Bewsee added, "It still depends on the quality of the person elected."

But Bewsee, like others in the city, is uncomfortable with the idea of the governor, not city residents, dictating that the question be on the ballot. "Something like this should come from the voters, not the governor," she said.

Bewsee also regrets that many voters will likely see the question as a referendum on the job being done by Sarno. "It's going to be like a popularity contest for the current mayor, and it's going to be hard for people to think about the bigger question," she said.

Ciuffreda said that the proposed changes have nothing to do with Sarno specifically; in fact, the Chamber committee began meeting during the Ryan administration, with an eye on the eventual departure of the Control Board. "We really did work hard at taking the person out of the seat and concentrating on the seat," he said. And if voters do approve a longer term, he noted, the change won't affect the winner of this year's election.

Sarno is opting to stay out of the public debate over the term extension. Perhaps his reticence springs from accusations leveled last year by Coakley-Rivera, who accused him of pushing to extend the term and increase the mayor's salary. (Chamber officials insisted the push came from them, not Sarno.)

Contacted by the Advocate for the mayor's thoughts on the ballot question, his office issued a general statement: "Mayor Sarno is honored to have this opportunity to serve the residents of the City of Springfield as Mayor. The voters in the City will rightfully have the opportunity to decide whether their Mayor is elected to a term of two years or four years."

*

Ciuffreda is conscious of some residents' belief that major governmental changes shouldn't come from the business community, but rather from residents.

When the Chamber's Governance Study Committee began its work, he said, members looked at the various ways a term extension question could make it on to the ballot, including by home rule legislation or by a citizens' petition. In fact, he said, the Chamber had started pursuing a petition drive but dropped that plan at the request of the Finance Control Board, which preferred that various changes not happen in piecemeal fashion.

That detail of the ballot question's history won't do much to appease those residents and local politicians who have resented the power wielded by the Control Board over the last five years. But at the end of the day, Ciuffreda notes, it's voters who will decide whether to increase the term. "The people will have the ultimate say," he said.

Before that happens, there needs to be more public conversation about what the change would mean. "It behooves somebody to have some discussions in the city about it," said Bewsee. Have longer terms worked in other cities? Have communities that have extended their mayoral terms come to regret it? "That's the kind of information we deserve to have before we vote on it," she said.

As the election nears, the Chamber will hold public events to discuss the question, although clearly, these events will come from a pro-extension perspective. "We certainly want to be part of the public process," Woolridge said. "My hope and expectation is that people will see the good reasons and logic for wanting to go with four years."

The Chamber has already sought public input on the question, and will continue to do so, added Ciuffreda. "It's not just a Chamber of Commerce issue," he said. "We think it's got community support."

An extended term, Ciuffreda added, would give voters an opportunity to honestly evaluate their mayor. "You're really going to be able to tell if this person is able to move the city ahead in four years," he said. "Over a four-year term, the results of that person are really obvious—or the lack of results."