Last summer, on the evening of July 5, an 18-year-old Springfield driver named Louis Jiles was pulled over by two city police officers. Within a few minutes, what had begun as a seemingly routine traffic stop ended with one officer firing three shots, at least one of which landed in Jiles' right wrist.

The Springfield police maintain that the officers behaved appropriately given the circumstances. According to police reports, Jiles failed to follow police orders to pull over after he'd run a red light, and then, when he did eventually pull over, ignored the officers' commands to show his hands. Instead, according to the reports, Jiles jumped into the backseat of his car, then re-emerged holding what appeared to be a gun, leading the officers to fear for their safety.

"It was an unfortunate incident," SPD spokesman Sgt. John Delaney told the Advocate in a recent interview. "It was also unfortunate that Mr. Jiles chose [to jump] into the backseat and not listen to the officers' commands."

In the end, no gun was found in Jiles' car. The officers involved were cleared of wrong-doing by both an SPD investigation and by the District Attorney. The DA also dropped five charges originally filed against Jiles, who pleaded guilty to one civil infraction, failure to stop for police.

But the case is far from resolved. Last month, Jiles filed a federal lawsuit against the city of Springfield, as well as the officers involved, David Barton and Stephen Hill; their supervisor, Captain Robert McFarlin; and Police Commissioner William Fitchett. The lawsuit accuses the officers of failing to provide Jiles with "prompt and appropriate medical attention" after the shooting, and of "attempt[ing] to conceal their unlawful acts by threatening him and filing a false police report." And, the lawsuit contends, because Springfield lacks an effective forum for citizens to bring complaints against the Police Department, Jiles and others in his situation have nowhere in the city to turn for redress.

*

In separate statements given to the SPD's Detective Bureau a few hours after the shooting, Officers Barton and Hill offered their version of the events of that evening.

The officers were working a 6 to 11 p.m. shift on an "anti-gang" detail in the city's H-2 sector, around Kensington Avenue. According to their statements, the evening had been off to a slow start when the officers noticed a gray Honda run a red light at the intersection of Dickinson and Oakland streets. While Hill ran a license check on the car in the cruiser's computer, Barton, who was driving, followed the Honda, turning on the blue lights and siren.

The cruiser pursued the car, which took several turns but failed to stop. "The vehicle was being operated in an erratic manner," Hill said in his statement. "Not really fleeing us but not stopping. I was sure that the operator knew that we were trying to pull him over. This fact was confirmed when he started to pull over and then took off again."

Finally, the officers said, the driver pulled over abruptly on Kensington Avenue—"a known gang area," Barton noted in his statement.

Barton stopped the cruiser and approached the Honda. According to his statement, the officer arrived in time to see Jiles jumping over the driver's seat and into the back of the car, where Barton lost sight of him. "I yelled to the operator to show himself or show his hands, something like that," Barton said. When Jiles reappeared, the report continued, he was facing the back of the car, looking directly at Hill, who stood on the street by the Honda's rear.

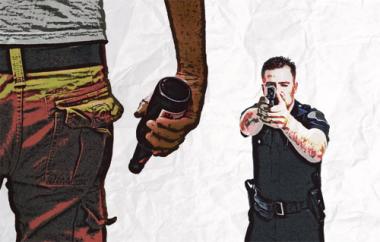

"I saw the operator's hand come up and I could see something in his hand," Barton's report continued. "It looked like the object in his hand was a gun, it was round and shinny [sic], and the guy was pointing it towards my partner. I yelled 'Gun' to my partner, Officer Hill."

Standing behind the Honda, unable to see the driver, Hill said he felt in danger; he was also worried, he said, about the safety of several people, including children, he'd noticed in the area. Hill had his gun pointed at the car's rear window when he saw the driver pop up with his hand by his head, according to the report.

"I could see something in his hand. … I believed that what I saw was a gun barrel," Hill's statement continued. "At this time Officer Barton yelled out, 'gun, gun.' …I fired my service weapon at the individual in the vehicle. I fired three rounds at the individual. I fired until the threat to me, my partner or the public was no longer present."

Hill then approached the car, his gun still drawn, he said. After Jiles, who was bleeding from the forearm, put both his hands outside the car to show he was unarmed, the officers frisked him, then sat him on the curb, Hill said. According to both officers' statements, Hill gave Jiles first aid while they waited for an ambulance to take him to Baystate Medical Center.

According to a police report, when officers searched Jiles' car, they found two beer bottles, an unopened one in the center console and another, open one, in the back of the car. No gun was found.

*

Jiles' lawsuit, filed in U.S. District Court, offers a very different version of events.

Jiles' eight-page complaint suit does not address the incident that led to Jiles being pulled over by police in the first place, or the allegations that he initially did not pull over when pursued by the cruiser. But the suit does contend that Jiles did raise his hands when ordered to by the officers, and then was shot in the wrist by Hill.

After being treated at Baystate, the complaint continues, Jiles was taken to the police department, "where he was interrogated by Springfield Police Officers and a statement was taken." After being booked, Jiles was allowed to leave on bond. Two days later, he was arraigned on a number of criminal counts, including unlicensed operation of a motor vehicle, failure to stop for police, assault with a dangerous weapon, and reckless operation of a motor vehicle. He was also charged with having an open container of alcohol in the car, and of being a minor transporting alcohol.

Within a couple of days, however, District Attorney Bill Bennett dropped all criminal charges against Jiles, who pleaded guilty to failing to stop for police—a civil offense—and paid a $100 fine. "Although the defendant acted foolishly and immaturely when he tried to evade police, there is no reasonable basis to conclude beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant intended to assault the officers," Bennett said at the time.

The DA also declined to press charges against Hill and Barton, and referred to Jiles' shooting as a "mistake," saying the officers mistook a beer bottle Jiles was holding for a gun.

But the matter was not over: Six days after the shooting, Jiles requested a police investigation of the officers' conduct. In October, an arbitrator hired by the city held a hearing, where he found the officers had not acted with malicious intent. Barton and Hill, who'd been assigned to desk duty since the incident, were allowed to return to regular duty. Jiles' lawsuit disputes the findings of that hearing and contends the arbitrator was "inappropriately prejudiced" because of ties with the SPD.

In an interview with the Advocate, Jiles' attorney, Perman Glenn III, disputed the claim made by the officers that they shot his client after he'd jumped into the back of his car. "Logic tells us that if somebody's shot in the back seat, there's going to be blood in the back seat, or blood splatters," Glenn said. But, the attorney said, an expert hired by his firm examined the car and found no blood in the back. Instead, the expert found a pool of blood by the emergency brake as well as blood on the front dashboard, "which is consistent with [Jiles] having his hands raised and being shot in the wrist," Glenn said.

According to the lawsuit, the bullet to Jiles' wrist caused permanent nerve damage. He continues to suffer both physical and mental pain, and faces ongoing medical costs, the suit said. Jiles, who is asking for a jury trial, is seeking punitive damages, financial compensation for pain and suffering, as well as his legal costs.

Glenn said his client is now a student at Springfield Technical Community College, where he finds his injury makes it painful for him to use a computer. While Jiles has yet to declare a major, the attorney said, ironically enough, he's interested in studying criminal justice.

Mayor Domenic Sarno declined to comment on the case, since the lawsuit is still pending. He referred questions to City Solicitor Ed Pikula, who did not respond to an interview request from the Advocate.

Sgt. Delaney, the SPD spokesman, disputed Glenn's allegations about the police officers' behavior. Both Barton and Hill had been cleared by the District Attorney and by the arbitrator, he said, and the department is confident they will be vindicated in court as well. "They're good officers," Delaney said.

But to Glenn, the findings of the District Attorney and the SPD don't carry much weight. Over his career, Glenn has often been highly critical both of the Springfield police's treatment of suspects and the law enforcement community's quickness to close ranks to protect officers—leaving the public with little recourse.

In theory, there is a forum where residents can air concerns about the SPD: the Community Complaint Review Board, a mayoral-appointed body that was created after the dissolution of the city's Police Commission. The CCRB, created at the end of the Ryan administration, had sat inactive for months after Sarno took office last January. It was finally reactivated last summer, in part because of public outcry after the Jiles shooting.

Jiles, in fact, did file a complaint with the newly revived CCRB. The board dismissed his complaint. In the lawsuit, Glenn contends the CCRB—which can review internal SPD investigations but lacks the power to interview witnesses or subpoena information—did not have access to all the relevant information about the Jiles case.

Indeed, the board has so little power that many question the point of its existence. "[T]he CCRB has neither independent investigatory authority, nor the ability to offer any recommendations or sanctions of its own," the lawsuit noted. "In the event that the initial [Internal Investigations Unit] investigation and disciplinary actions are inadequate, the only avenue of redress available to the CCRB is to return the case to those same authorities and request a review. This procedure is manifestly inadequate to serve as the intended check on police power that it is intended to be."

In Jiles' case, Glenn told the Advocate, the CCRB "never contacted us. They never wanted any of the input we had. They never wanted to interview him. It was a surprise to us that they had even concluded the investigation." Glenn's dissatisfaction is not with the board's members, he added, but rather its structure. "I really like the makeup of the board, but they have no power," he said.

While the CCRB's predecessor, the Police Commission, had significantly more power—that board could discipline officers, for instance—it, too, often faced criticism, including charges that its members, who were also appointed by the mayor, too often favored the police over the public. After 24 years of practicing law here, Glenn does not sound confident about citizen complaints against police ever getting a fair hearing in the city—leaving residents who believe they've been wronged to seek relief in court, as Jiles has.

"These [city] investigations are over before they start," Glenn said. "I just don't know what the solution is… other than to continue with these lawsuits and continue to try to make some progress."