Originally, a confluence of railroads put the town of Palmer on the map.

The town is made up of four villages: the area right by the tracks is known as Depot Village. Palmer calls itself "the Town of Seven Railroads" in honor of the many train services that ran through or from the town. Today, the town's a hub for three freight rail systems that crisscross in the rail yard on a fancy bit of track work known as the Palmer Diamond. For train enthusiasts, Palmer is a kind of train Mecca, and reliably a group of odd-shaped men and women line the tracks, tripods and cameras poised, ready to capture the action on the busy rails.

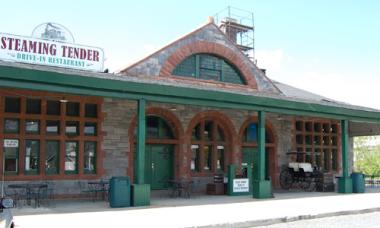

Not far from this oft-photographed four-way rail crossing stands a magnificent stone station, beautifully restored to much of its Victorian majesty. It was built to be expansive, but also fit into the odd wedge of space available between the rails, and from the air, it's a trapezoid. From the ground, though, the awkward shape is hidden behind an open face with a veranda stretching the width of the building. Beneath a low, expansive roof, arched windows and huge wooden doors lead inside to a restaurant that makes elegant use of the cavernous waiting room. Outside is a retired steam engine and an old dining car where brunch and private banquets are served.

Even though freight trains still rumble through this transit hub all day long, and there's the restored train station ready to resume selling tickets, not even the two Amtrak trains that regularly pass back and forth through Palmer daily accept passengers. For decades, the Vermonter, which travels between St. Albans, Vermont and Washington, D.C. has routinely had to pause there for a few minutes to change tracks. Day in and day out, the train stopped at Palmer, but the doors never opened; no one got on or off. The Lakeshore Limited between Boston and Chicago routinely just breezes on through.

Effectively, as far as passenger service goes, Palmer's fallen off the rail map. The town's eager to get back on, and town officials have been working toward that goal for a long time, writing letters, courting statesmen, and honing a compelling argument for their reinstatement.

Recently, rail fans and business owners in Holyoke, Northampton, and Greenfield have been rejoicing in

news of a Pioneer Valley Planning Commission (PVPC) proposal to spend federal stimulus money on returning passenger rail service to those cities. Proponents of the plan, known as the Knowledge Corridor project, began two years ago, investigating ways to increase rail ridership in Western Mass, and it was conveniently far along enough in the planning when President Obama's stimulus funding was approved. There is $80 billion available nationally for rail improvement projects; the PVPC is planning on asking for approximately $30 million. Initially, the plan was only to redirect the Vermonter service along the river route (thus cutting off Palmer and Amherst), but already there's talk of commuter service and high speed rail following not far behind.

Understandably, Palmer rail fans and business owners didn't share the excitement. Some questioned how and why the PVPC, a private nonprofit with little rail transit experience, could dictate terms for the region. Just because Dana Roscoe, a leader of the Knowledge Corridor project, assures the Pioneer Valley that its plan best suits the needs of the region as a whole, why are member municipalities such as Amherst and Palmer supposed to believe that—especially when their data and experience say otherwise and haven't been seen?

Palmer lives and breathes trains, and it's a mistake trying to tell them about the train business. When I tried, I got invited out to lunch at the Palmer Union Station and had my head turned around.

*

After reading a piece I'd written last month on the PVPC's rail plans, Blake Lamothe, chairman of the Palmer Redevelopment Authority, sent me a strongly worded letter taking issue with many of the sentiments he deemed anti-Palmer and facts which were, he wrote, just plain "wrong." He advised me that he was going to air his dissatisfaction publicly on his show, "Seven Towns, One Station" on WARE radio (1250 AM; the show runs Fridays at 1 p.m.).

I called Lamothe to let him tell his side. He agreed, and we met for lunch at the Steaming Tender, the restaurant housed in the old station. In addition to his official public title, Lamothe also owns the restaurant (and a number of other businesses in Depot Village) and is responsible, along with his wife Robin, for the revitalization of the building.

We filled our plates at the buffet and then sat at the bar. While he detailed his case for prioritizing an east-west rail route through Palmer over spending stimulus money to develop the Connecticut River Knowledge Corridor [his position is described in detail here], his beautifully renovated station argued its own case.

The low veranda roof doesn't prepare you for the huge, vaulted waiting room inside. The thick beams supporting the tall ceilings, the dark wood paneling and brick arches are grand, but informal and warm. The place feels like some English country lodge where hunters might relax with their hounds after a long day riding through the forests and across the heather. As we ate along with a room-ful of happy diners, an endless line of trains marched by the windows on either side of the station. It's like a train aquarium with a new species of freight drifting past every time you look up from your plate.

There really isn't anywhere else in the Pioneer Valley where a rail fan can sit back and watch the trains go by. In Holyoke and Northampton the lines have been so neglected that trains can only travel slowly, and they do so rarely. The rails in Greenfield along the Connecticut River are similarly in bad repair, but they get more regular train traffic running east and west along the Mohawk Trail on the old Boston and Maine Rail Road. Springfield's got a lot of rail traffic, but its station with banks of coin-operated dispensing machines is not a place anyone would spend time willingly.

After we'd finished eating, Lamothe took me through the kitchen, behind the station. A row of photographers lining the tracks greeted him with a hearty, "Hey, Blake!" before focusing on the next engine heading up one of the rails. He took me along the tracks toward the Palmer Diamond, explaining that we were walking where the passenger platform had once been. He'd restored the roof to the freight platform on the other side of the building, but he hadn't restored the much longer passenger platform, which had exceeded the length of the building considerably. He'd love to restore the entire span, but, turning back toward his station, he shows where an abbreviated platform could be erected quickly if only a train would open its doors there.

Before the recent news that the PVPC was looking to fund its own train vision, Blake Lamothe had been busy looking to fund a financially more modest vision that was easier to implement and could have greater reach more quickly.

He points to a rectangle of earth nearby. "That used to be a stairway up from the underpass. There's a road underneath there. The stairway got sealed up back in the '70s after trains stopped picking up passengers. I met the guy who sealed it up, and he wasn't sure, but he thought beyond a layer of cinder blocks, they'd just thrown some dirt in. It would be easy to reopen and clear. With it opened up, it's less a minute from Main Street, and you're here, waiting for the train."

He took me down the slope behind the granite wall supporting the rails and letting Depot Road pass beneath, and after he showed me the cinderblock wall hiding stairs to the surface, he pointed down the road. Less than a hundred yards away is a field he says is available to be turned into a 680-car parking lot. On the other side of the road, in a lot that currently houses Palmer DPW equipment (Lamothe assures me it could be relocated), he envisions a park with a small-scale train for children, similar to Northampton's Look Park.

His most exciting plan for reviving his rail station he saves for last.

*

In 1881, the Boston and Albany Rail Road commissioned three train stations from the Boston-based and internationally known architect Henry Hobson Richardson; two smaller ones in Auburndale and North Easton, and a larger one in Palmer.

During the 1870s, Richardson had established himself as the preeminent architect of his time. While only in his 30s, he designed buildings such as Trinity Church in Boston, the State Capitol in Albany, the State Asylum for the Insane in Buffalo, and a host of banks, churches, office buildings and homes across New York and New England. Raised in New Orleans, he was only the second American architect to be trained in Paris' Ecole Des Beaux Arts.

Because the Civil War squeezed his parents' finances, Richardson wasn't able to complete his training there, and he developed a distinct architectural style that reflected less the Parisian school's classic sensibilities (lots of alabaster-white columns) than something more medieval, dark and earthy. Instead of Rome and Greece being his chief influences, he was impressed by the fortresses and cathedrals built during the Middle Ages (particularly the Romanesque buildings of southern France), and the contemporary works of British architects William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, who also worked with that aesthetic. The writer and art critic John Ruskin was also an influence.

Richardson's hallmark style for churches, institutions and public buildings featured tall towers, huge, arching entrances and windows, and thick walls of rough-hewn stone; even after his untimely death at 47 (five years after winning the railroad station commission), his influence continued throughout New England, and many buildings—such as the Northampton train station, the Hampshire County Court House and the Amherst Town Hall—look like his work, but are not. Some were built by the firm of Shepley, Rutlan and Coolidge, members of Richardson's staff, who completed many of his projects and continued to build in his style for years after his death.

But the Palmer station is an original Richardson design, and one of the few of his stations that have not been destroyed (after the success of the first three stations, he was commissioned to do five more). All take a very different direction than his other work. Instead of the towers and in-your-face magnificence of a building like Trinity Church, the stations are much simpler and closer to the ground. Still distinctly Richardson, his stations are dignified, but modest and inviting, like an English country cottage or horse barn. As the architectural historian Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer wrote shortly after his death, "… Our country railroad stations had so long been hideous makeshifts or futile attempts at prettiness (and in either case synonyms for fragility and parsimony), …[whereas] the majority of [Richardson's] stations are as simple and right in feature as they are appropriate in general effect, while none of them show more than a touch of decoration. All parts are as carefully built and finished as in his monumental structures…."

And if having one of the few authentic Richardson rail stations isn't enough to return Palmer to its rightful place on the rail map, how about also having on the grounds an Olmsted pocket park designed to complement the station?

*

Frederick Law Olmsted, of course, is recognized as the founder of American landscape architecture. Among his many ahcievements are New York City's Central Park, Boston's Emerald Necklace, the grounds around Niagara Falls and Yosemite, and the campuses of Mount Holyoke, Amherst, and Smith colleges. Richardson and Olmsted were friends. After a long working relationship with the architect Calvert Vaux (the co-designer of Central Park) was coming to an end, Olmsted began working more and more with Richardson. It was Richardson who convinced Olmsted to buy a house in Brookline, Mass., so that they could be neighbors as well as collaborators, and it was in 1883, just as Olmsted moved in, that he received the commission to add a park to the Palmer station, along with a number of other stations.

Toward the end of our meeting, Lamothe mentioned that, come June, he'd finally be signing a bill of sale on a dusty lot that abuts his parking lot outside the station. The barren patch of ground that now has a few tremendous old air conditioners on it, plus other railroad refuse, was once that park—a small park where people could wait for their train. Lamothe took me to the back of the lot, and through some old rails stacked like giant pickup sticks and a patch thick with briars, he pointed to a long wall of rock that arched up out of the ground. More rough stone sloped back under the arch, and Lamothe explained that it was all that remains of a huge, landscaped grotto that once had bubbling fountains. Once the ground sloped down from the station into a submerged glade next to the grotto, but since then the glade had been filled in with 15 feet of dirt.

Lamothe has bought the original drawings of the small park from the Frederick Law Olmsted archives, which are located in Olmsted's former Brookline home, now a museum. Once he owns the land, he plans on excavating the lot and restoring the park.

*

On May 19, the PVPC held the second of two public meetings at the Clarion Hotel in Northampton (the other was held the night before in Springfield) to discuss its initiative to reroute the Vermonter along the Connecticut River. While Amherst town manager Larry Shaffer made a plea that the PVPC not freeze him and his town out of the discussions, by and large the mood in the packed room was joyful and excited. Many expressed a sense of astonishment at the idea of one day maybe being able to board a train station again in their own town. Many said that only months ago, they wouldn't have bet on its ever happening.

While I share this excitement, after talking to Lamothe, I began to wonder if the excitement along the river is sufficient to make a rail line there successful. Judging by the grey hair and bald heads present at the PVPC meeting, I'd guess the average age of attendees was something like 55, with many being older than that. The serious advocates of rail travel seem to belong to a generation that grew up with rail service and understand the subtle and not-so-subtle reasons steel wheels on rails beat rubber ones on a road any day. But having gone without rail service for so long, and by letting our rail infrastructure deteriorate (Holyoke once had its own original Richardson station, too), I'm not so certain any amount of funding can restore the passion and devotion needed to make such a venture thrive. Many of us who are excited about trains may not even be around decades later when PVPC's plans come to fruition. Just because we build a new, expensive rail route, will anyone really ride it? Or will the public simply be funding improvement in a private rail line its current owners weren't willing to make themselves?

Along with the passion, Palmer and the Steaming Tender already have around a thousand patrons a week who come to enjoy the station. Trains already run through the town, and already $30 million has been invested to maintain the line between Palmer and Amherst. Before any decisions are made or applications are submitted, it would seem to make a lot of sense for PVPC planners to stop telling the Valley what's good for them and start listening to people like Blake Lamothe.

An overview of the Palmer Redevelopment Authority's position can be found here.