I am not a religious person, never have been. My lapsed Catholic mom and my atheist dad agreed to have me baptized a Catholic, but I don't remember going to mass except on Christmas Eve. When I was about seven, mom briefly joined an Episcopalian church, where I attended Sunday school a dozen times or so. After that, my churchgoing was limited to occasional trips with my grandmother to the Broad Cove Church in Cushing, Maine, where she attended Sunday services faithfully in her later years, though I always suspected that her motivation was more social than spiritual.

While my sister and I were taught to be tolerant of all religious faiths, we were also encouraged to do our own thinking, to follow our own sense of spirituality, to the degree that we had one. I didn't think much about spiritual matters until I was in junior high school, when I began reading some of the American Transcendentalists such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Vaguely aware that I was my happiest when I was in the woods or on a river, fishing or just generally communing with nature, I found kindred spirits in Thoreau and Emerson, whose words helped shape what would become my philosophical if not spiritual view of the world. To this day, I find comfort in the little snatches of their prose that I committed to memory when I was young.

It wasn't hard for me to wrap my head around Thoreau's "Distrust any enterprise that requires new clothes" or "I would rather sit on a pumpkin and have it all to myself, than be crowded on a velvet cushion," or "If a man walks in the woods for love of them half of each day, he is in danger of being regarded as a loafer. But if he spends his days as a speculator, shearing off those woods and making the earth bald before her time, he is deemed an industrious and enterprising citizen."

And no line have I repeated more often in my adult life than Emerson's "A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines."

Given my upbringing, then, it is perhaps not all that surprising that I am a reluctant observer of holidays, even those that have broad secular appeal. Although Christmas in my house is more about decorating trees and hanging out stockings for Santa to fill than it is about a little town of Bethlehem, I still groan at the prospect of treating Dec. 25 as a special day, a day significantly different than the other 364 days in the year. To me, they're all special. Who needs a holiday as an excuse to make merry, to gather with friends and family, to take a day away from work?

There are, however, a few days on the calendar that I do observe in my own way. Fortunately, these are days that, while widely acknowledged as significant, particularly by meteorologists, have so far been spared the indignities visited on most "official" holidays by Madison Avenue advertising executives. Indeed, if and when it becomes commonplace to gather at one's in-laws' for a ham or roast beef dinner to celebrate the summer solstice, it may well turn June 21 (or June 20 in some years) into just another day to me.

*

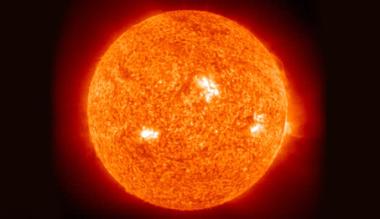

The word solstice says it all: the name is derived from the Latin sol (sun) and sistere (to stand still). At the solstices, the sun stands still in declination; the movement of the sun's path north or south appears to stop before reversing direction. As the summer solstice (in the Northern hemisphere) approaches, the noonday sun rises higher and higher in the sky on each successive day. On the day of the solstice, its rise compared to the day before is nearly imperceptible, as if the sun is standing still.

To a layman like me, the standing still part of the solstice is merely an interesting footnote to a much more compelling narrative: the summer solstice is, speaking in the vernacular, the longest day of the year—just as the winter solstice, around Dec. 21, is the shortest day. The two solstices, along with the equinoxes in March and September, which signify the midway point between the two solstices, mark the beginning of a new season. As a New Englander since birth, I've consciously and unconsciously organized my life around the seasons—just as the arc of Anthony Powell's 12-volume series of novels, A Dance to the Music of Time (inspired by the painting of the same name by Nicholas Poussin), follows the cycle of seasons.

Even without a deep understanding of the astronomic principles at play—I'm still not exactly sure why the earth's tilt of 23.44 degrees is called the "obliquity of the ecliptic"—I have a deep appreciation for the effect created by the earth's axis of rotation's not being perpendicular to its orbital plane. Without the tilt of the earth's axis, there would be no seasons. When summer occurs in the northern hemisphere, for example, it is because we receive more direct sunlight than the southern hemisphere, where it is winter. At the equator, there really are no seasons. Although it is a popular misconception that the sun is overhead every day at the equator, it is true that all days of the year are about the same length—12 hours. In the tropics, seasons are characterized not by the length of the day but by weather conditions: the dry seasons and the rainy seasons.

*

While you may have a little trouble finding a summer solstice greeting card—in fairness, I didn't check with Hallmark to see what it has available—the day has been celebrated by various religions throughout history. Ancient Druids called it Alban Heruin ("Light of the Shore"). In ancient Gaul, the summer celebration was called the Feast of Epona, named after the goddess of fertility, sovereignty and agriculture. Ancient pagans marked the day with bonfires, a sympathetic effort to help the sun warm the earth. Today, the neopaganist Wiccans have eight seasonal days of celebration, including the summer solstice sabbat called Litha—the counterpart to winter's Yule.

Regardless of the religious tradition from which the various solstice celebrations spring, the basic themes remain the same: abundance, fertility, magic and empowerment.

Without being grounded in any particular religious tradition, I apparently have some affinity for the ancient so-called pagans, whose rituals were tied to observable—and therefore predictable—changes in the physical world around them. And though I may be content to accept the movement of the sun in the sky as a natural occurrence needing no metaphysical explanation, I am not so strict a rationalist as to deny that the solstices have certain magical qualities.

For me, however, the magic of the summer solstice comes not in the form of woodland faeries—not Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream kind of magic—but in feelings that come from an acute awareness of my own mortality. Time: that's what the solstices mean to me. At the summer solstice, I have the feeling of time expanding; at the winter solstice, I feel time contracting. Both feelings are fleeting, due, I suspect, to the knowledge that, from the summer solstice, the days will get progressively shorter until the winter solstice, whereupon we begin to move toward the light again.

The significance of the summer solstice to mortal beings, not unlike any other holiday that comes but once a year, is heightened by the realization that one will see a finite number of solstices in one's life. As I get older, I feel increasingly the need to squeeze as much living into the longest day of the year as I can.

I can't say I planned it this way, but I observe the summer solstice (and winter solstice) without the assistance of much that would pass for an annual ritual. Some years I go fishing. Some years I spend the day working in the gardens, following that up by a big evening meal, served al fresco, and a big bonfire. There are only three general rules to my observation: I awaken in time to see the sun rise, stay awake long enough to see the sun set. And I spend the entire day outdoors.

I haven't made plans yet for the coming solstice and probably won't until it is nearly here. Perhaps this will be the year that I pack up a tent and some grub and head off on a hike, walking as far as I can go during the daylight. The idea for such a trip came from reading the journals of Richard L. Proenneke, a man who lived alone in the Alaskan bush from 1968, when he was in his early 50s, to 1999. Proenneke, a Thoreau of his time, often marked the summer solstice by taking a long day trip, one that would have meant walking in the dark at any other time of year.

"Up with the sun at four to watch the sunrise and the sight of the awakening land," Proenneke wrote in the late spring of 1968, as the solstice neared and he thought about all the things he wanted to do and see. "It seems a shame for eyes to be shut when such things are going on, especially in this big country. I don't want to miss anything."