Greenfield has just wrapped up one of the strangest mayoral elections in Pioneer Valley history. Town councilor Bill Martin, initiating an aggressive write-in campaign only 16 days before an April 21 four-way primary, garnered enough votes to take second place, knocking incumbent Christine Forgey, Greenfield's first mayor, from the final ballot.

Forgey, mayor since 2003, apparently failed to take the preliminary election seriously, and paid for that mistake with her job.

"It was freezing cold and raining on that day," explained Forgey supporter Betty Guetti. "Elderly and disabled people stayed home. People thought she was a shoe-in, so didn't come out for the primary." As the polls closed, two mayoral candidates emerged—fellow town councilors Bill Martin and Alfred Siano, both Greenfield born and bred.

Martin, regarded by many observers as the underdog in his race against popular, easygoing town councilor Al Siano—the candidate favored by many self-described "progressives"—campaigned vigorously for another six weeks, and emerged with a stunning landslide victory in the June 9th general election. Now Martin, the man who made his mark as chair of the powerful Greenfield Redevelopment Authority (GRA), is the new, pro-business mayor of a town that's become known in recent years for its caustic, personality-driven local politics.

Al Siano had been described as "the darling of the Al Norman crowd"—referring to a coalition of individuals who, more than 10 years ago, successfully blocked the construction of a WalMart on the Mohawk Trail. Whether or not this characterization of Siano is entirely accurate, old perceptions die hard. Siano, perhaps hoping to appeal across the aisle, was careful, during the election season, to avoid making many specific statements about his plans, positions, and alliances.

"He's the guy who everybody likes. He's got political capital—he doesn't have a lot of baggage. He might be able to bring some civility to Greenfield, which we desperately need. It's hard to describe just how toxic the political climate is here. People don't get involved in volunteering for boards or running for office because it's so bad," remarked a young woman at the polls in explaining her support for Siano.

In contrast to Martin's fine-grained action plans, Siano ran largely on apple-pie generalities: "New Leadership for a Better Greenfield." "Open Government." "Quality of Life." "Regional Cooperation." He promised a new respect for process, where everyone would be heard. He emphasized the importance of restoring the reputation of the schools, asserting that parents would keep their children in the district if a sense of stability could be reestablished.

But Siano proved remarkably difficult to pin down. For years he had promoted the idea of a split tax rate, with businesses paying more than residences. But during mayoral debates, he waffled on this issue. He had built a basis of support by opposing big box development, but seemed to favor the idea during his campaign.

His expression of support for a proposed 47-megawatt biomass plant left many of his supporters scratching their heads. Many voters were perhaps left wondering—what does Siano stand for, aside from a desire to reform Greenfield's political atmosphere?

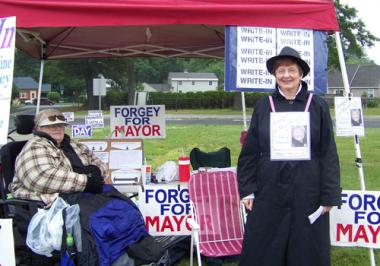

But Siano had more than enough clout to oust Forgey from the race in April. In the wake of her loss in the primary, Forgey played a coy game about her continued candidacy. In an interview with WHMP radio host Chris Collins, she maintained that she would not wage a write-in campaign because of her "respect for process." But when queried, she revealed that she would indeed vote for herself. "What Greenfield needs now is somebody with proven leadership skills, who has been dedicated to the job, who gets it… So on June 9th, I'm going to write my own name in." (Forgey's ambiguous write-in campaign ultimately yielded around 500 votes, not enough to influence the outcome.)

Martin was once Forgey's strongest supporter. He managed her mayoral campaign in 2003, after a change in town charter created the position. The two collaborated on projects such as the Bank Row Urban Redevelopment District, and joined forces in their attempt to attract a big-box retailer to town. Lambasted on web-based forums, they were described as members of a local "pro-growth super majority," or "PGSM," and gained the special enmity of the so-called Normanites.

Forgey's campaign to attract a big box retailer pitted her against this faction. In pursuit of this objective, Forgey promoted a zoning change, a waiver of local wetlands regulations, and, most notably, a reconstruction of the conservation commission, choosing, in 2007, not to re-appoint ConsCom chair Steven Walk and member Joan Adler. "Walk clearly knew more about the environmental issues before this Commission than any other serving member," reported Greg Aubin, former school committee chair and editor of the online Greenfield Optimist. "No one questioned his commitment to providing a fair hearing process in which all sides were heard. Only one person had a problem with such balance—the Mayor of Greenfield."

Forgey seemed to be a magnet for controversy. A million dollars went missing from the school budget in 2008, prompting the Town Council to call for state oversight of school finances. A festival of finger-pointing ensued, providing fodder for the press, the blogosphere and the radio talk shows. Interim Superintendent Marcia Evans suggested that blame be laid at the feet of her predecessor, Joe Ruscio, who, by some counts, implemented programs with no basis in funding.

A Greenfield Recorder article quoted Forgey, a voting member of the school board, as having "no memory" of approving the budget. Two school administrators were put on paid leave, and school finance subcommittee chair Dalton Athey threatened to resign, citing a lack of cooperation from administrators. Aubin refused to step down from his position as school committee chair—even after a vote of no confidence by his peers and a call from Forgey for his resignation.

Meanwhile, the schools were losing money—nearly $ 3 million dollars in 2008—as frustrated parents removed their children to other districts. Critics suggested that Aubin and his "Gang of Four" (Aubin, Athey, Donovan Eastman and MaryElen Calderwood) were attempting to weaken and discredit the sitting mayor through the venue of the school committee.

School board candidate Keith C. McCormic opined to the Advocate that "some of the Normanites decided that they didn't like Forgey. They couldn't get elected to the Council, but the school committee happened to be ripe for the picking. They got on there—that's the Gang of Four—and have made a stink about funding…Recently the Town Council cut a small amount, around $133,000, from the school budget. [School Commitee Chairman Dalton] Athey just hit the roof… instead of trying to work with the reality of the situation. The school committee has been dominated by the anti-sprawl people."

"That analysis is too simple," remarked WHMP's Collins, who has followed Greenfield politics for 15 years. "The Gang of Four is not fighting WalMart from the school committee. There is long-standing conflict between the school committee and Town Council, which has to do with a host of reasons, including state education reform, which gives school boards budgetary autonomy. Yes, there are factions which were revealed during the WalMart fight. Those factions are still fighting, but it's not just about the store. At one time, WalMart was the elephant in the room. The elephant has left the room—and now we're dealing with what the elephant left behind."

As Forgey's popularity declined, Martin started distancing himself from her, building his reputation as the chair of the Greenfield Redevelopment Authority (GRA).

The GRA sprouted teeth in March of 2007, when its plans for an Urban Renewal District were approved by the state, granting the Authority the power of eminent domain. The district includes a 19th-century business block known as Bank Row, the Garden Cinema, an old Toyota dealership on Olive Street, and properties including the Mix-'n'-Match building and the Salvation Army. The district plan includes a parking garage, a multi-modal transportation center, reuse of the theater building and the development of new storefronts and upper-story residential space.

Martin made headlines in 2008 by marketing several buildings within the district to Jordi Herold, the founder and long-time proprietor of Northampton's Iron Horse Music Hall. Herold, in the years since he sold the Horse, has built a second career in preservation-based real estate development. Last week, he announced plans to transform the Garden Cinema into a performance space, and is moving ahead with his three Bank Row properties.

The possibility that Amtrak will return to Greenfield, as proposed by the Pioneer Valley Planning Commission, fits in well with the GRA's plans for a transportation center at the Toyota site. An adjacent parking garage will be convenient for commuters and shoppers alike. A set of incentives for upper-story residential development is being put in place. This design-centric, bricks-and-mortar approach to downtown revitalization is reminiscent of Northampton's legendary Mayor David Musante, and has appealed across the political spectrum—even, perhaps, to a certain portion of the Normanites.

It cannot be denied that much of Martin's support came from the old guard—from conservative townies. "Forgey's had her chance," quipped one elderly sidewalk commentator on the evening of the election. "And Siano I associate with Al Norman, the anti-WalMart guy. Who the heck is Norman to tell Greenfield what's best for Greenfield? It's insulting. He's just polishing his national reputation. When my daughter wants to buy clothes for my grandson, she doesn't have a lot of money to spend and she doesn't have a lot of time. She shouldn't have to drive 20 or 30 miles to save a few bucks. Not everybody can afford organic this-and-such."

Martin's support for big-box retail, combined with his demonstrable success in revitalizing the downtown, probably drew voters of both blue and red persuasions. "Debate in Greenfield has been defined by the extremes," McCormic said. "But what we're seeing now is people rising up in the middle."

For people seeking middle ground, Big Box development doesn't seem to rise to the level of a hot button issue. There appears to be a growing sense that Greenfield is already having some success building its destination status in ways that aren't necessarily threatened by a Big Box retailer. If Greenfield's reputation as a cool place to live continues to grow, as it becomes increasingly a place people visit for unique local entertainment, shopping, restaurants and cafes, the debate about Big Box retail may become more nuanced and less volatile.

The Normanites have accomplished their aim—Forgey is gone. But their favored candidate, Al Siano, didn't even come close in the final election. The school committee's "Gang of Four" was dismantled in Tuesday's election, a new school superintendent is in place, and embattled economic development director Marlene Marrocco has resigned. Don't look now, but it's morning in Greenfield.

Or is it? A proposal for a 47-megawatt biomass incinerator is currently before the Zoning Board. Judging from a recent meeting, the opposition seems diverse, including fiscal conservatives, elderly homeowners, young parents and business owners. Will biomass become the new WalMart?

It might be difficult for Greenfield insiders to understand, but the town's ultimate success may depend on its relationship to the region. Tracey Schryba, an electrician from Colrain, expressed this view. "I wish that I could vote in this election," said Schryba, "because it's so important to the surrounding towns. Walmart will be one place where people can get everything. It will take away from surrounding towns—from farmers who are producing dairy and other goods, and smaller retailers in the hilltowns. And the biomass plant—we're going to see stuff getting clearcut that never was clearcut before. Greenfield residents are voting on issues that affect the entire region. We should all be allowed to vote in this election, everyone in Franklin County."