Harry Potter and The Half-Blood Prince

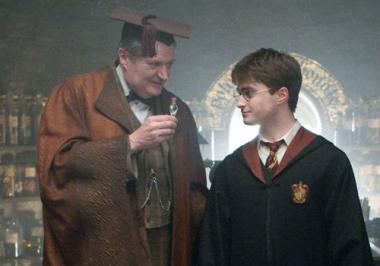

Directed by David Yates. Written by Steve Kloves, based on the book by J.K. Rowling. With Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson, Rupert Grint, Michael Gambon, Bonnie Wright, Helena Bonham Carter, Alan Rickman, Jim Broadbent, Tom Felton, Maggie Smith, David Thewlis, and Robbie Coltrane. (PG)

With Harry Potter and The Half-Blood Prince, the juggernaut film series reaches the penultimate installment in the juggernaut book series—yet there are two films yet to come. The final Potter story, it seems, has been judged too big to fit into one film, so Harry Potter and The Deathly Hallows is scheduled for a two-part release over the course of 2010 and 2011. After seeing Half-Blood Prince, which, at over two and a half hours, still has the slapdash aftertaste of a rush job, one can't help but wish the studio had taken a similar tack here.

It's not an awful film by usual standards, but Potter fans—by which I mean fans of the books—have memories as long and sharp as a dragon's tooth (they'll be sure to let me know if dragons don't have teeth) and this adaptation makes mincemeat of the story, plucking a juicy bit here and there, trimming away the rich, delicious, fat, and leaving behind a carcass that barely resembles the original meal.

Boiled down to its bones, the story is this: the young wizard Harry (Daniel Radcliffe) has returned to Hogwarts for a sixth year of training alongside his steadfast friends Ron and Hermione (Rupert Grint and Emma Watson). There he discovers an old book of potion recipes, inscribed with marginalia by "the half-blood prince," to which he grows increasingly attached. Meanwhile, school bully Draco Malfoy is skulking around the castle's hidden rooms on some devious mission or other. Being teenagers, the characters spend an inordinate amount of time falling in and out of love with one another, something the film dwells on at nauseating length. Swirling around the edges of the tale like ropes of smoke are the wraith-like forms of the dark-magic enthusiasts known as Death Eaters.

What's missing, despite the film featuring the death of one of the main characters in the series, is any sense of tension. In past installments—and in the book on which this film is based—the story of Harry's connection to the consummately evil Voldemort is the crux of everything, lending the story a frisson of intimate dread that recalls Greek myth. Without any real confrontation—there is no Voldemort in Half-Blood Prince, save for various mutterings about "the Dark Lord"—the film feels like a placeholder, as if the real action is being salted away for inclusion in the big finale.

Even without the drama of the book, Radcliffe et al have become familiar faces to moviegoers, and seeing them onscreen again, wands at the ready, feels like a reunion. Thanks to the phenomenal success of the series, they are joined once more by a constellation of British stars who could make "abracadabra" sound Shakespearean. Unfortunately, they are rarely given that chance.

Also this week: Coming to Northampton's Academy of Music on Friday Aug. 7 is Andrew Shapter and Joel Rasmussen's investigative documentary Before The Music Dies. Concerned by the increasing homogeneity of American popular music, the pair embarked on a cross-country journey—hearing the same few dozen songs from stations all along the way—in hopes of discovering the reasons behind the one-size-fits-all mentality of big radio.

The result is both entertaining and chilling. As Shapter and Rasmussen frame it, the villain is ClearChannel, the huge Texas-based media conglomerate that is the country's largest owner of radio stations. Started in the 1970s by a pair of San Antonio car salesmen, the company ethos was, from the start, based more on arithmetic than art; by applying the lessons of the auto industry to the radio market, founders Lowry Mays and Red McCombs quickly grew their fledgling station into a market leader, buying up smaller stations in other markets along the way.

But they couldn't have done it alone—not so long ago, a business whose tentacles reached so wide would have been illegal. The real story behind the rise of ClearChannel is the story of deregulation, and how the government was prodded into allowing one entity to control the majority of the country's airwaves—and, by extension, the viewpoints allowed to be broadcast. (ClearChannel's talk-radio arm is a conservative bastion anchored by Rush Limbaugh, Glenn Beck, Sean Hannity and Dr. Laura.)

That sense of conservatism extends to the company's music policy, and the effect it has—on musicians and their livelihoods, and on the future of the art itself—is the movie's angry heart. To expose that seismic shift in the music world, the filmmakers interview industry insiders, fans, and musicians including Dave Matthews, Elvis Costello, Branford Marsalis and a wonderfully testy Erykah Badu. Perhaps surprisingly, few of the commentators—however disgusted they might be with the ClearChannel behemoth—see the company as a harbinger of new music's death. After all, in the era of the Internet—where Pandora lets listeners fine-tune their own personalized stations—who still listens to the radio?

Should you miss Before The Music Dies during its Academy showing, you can watch it at home for free—if you don't mind a couple of commercials—on your computer. The film is included in the Music section at Hulu.com, a website that offers a wide selection of feature films, television shows, and more as streaming video. Other full-length music films featured include the Cuban music documentary Buena Vista Social Club and Storefront Hitchcock, Jonathan Demme's profile of British musician Robyn Hitchcock.

Music is just the tip of the iceberg: the easily navigable site offers dramas, comedies, documentaries, and science fiction, with big titles like The Last Temptation of Christ, Super Size Me, and the Jim Jarmusch hit Broken Flowers. Also in the mix is an abundance of schlock horror, plus a laundry list of television shows, including older shows that are a surefire way to induce nostalgia among 30-somethings (Welcome Back, Kotter, anyone?).

A joint venture between the ABC, NBC Universal, and the Fox group, the site has gone through some growing pains—the fact that it isn't available to users outside the United States remains a sore point with Europeans—but there's no doubt that it's the benchmark for online video. As broadband connections become the norm, Hulu and its inevitable imitators may become strong enough to replace your television—to a large degree, it has already replaced mine.