It was harder to find a steady stream of theme(s) in this weeks episode than it has been lately. In some ways, the producers were more heavy-handed with the symbolism, slipping in quick, David Lynch-like shots lasting only a few frames, combining wakefulness and dreams, blurring the lines between reality and fantasy, pressing importance on objects. In other ways, the characters were refreshingly stripped down, honest in their dialogue, and not speaking lines laden with hidden meaning. True, the writers did everything they could to remind us that this was a time of extreme racial tension, dropping Medgar Evars' name more than once and giving Pete the new storyline of trying to market to an integrated audience (it seems he might reach an understanding about race through economic necessity, which is interesting). But for some reason this episode did quite a but to re-tool the image I have of many of the characters. The writers slipped away from the personality-pastiches that, while successful in their conveyance of social norms, overbear the actual personalities of the characters (as actual as fictional personalities can be, I guess).

We see Mr. and Mrs. Draper in Sally's classroom. Betty can't fit in the desk she's offered, due to the fact that she's in the ready-to-burst-at-any-minute stage of her pregnancy. Sally's been acting out, they, and we learn. The scenes signifigance is not readily apparent, but sort of worms its way into the rest of the episode. Don's intrigue in Suzanne Farrell, Sally's teacher (who's namesake must have some signifigance), was further developed as the two shared the similar experience of suffering a death when they were Sally's age. The producers also took advantage of the change to use that surreal editing that would dominate the bulk of the episode. We learn Sally got in a fight with a "bruiser," as her mother describes her. We see the aftermath, Sally wiping blood across her cheek, just for a moment. And then we cut back to Don and Betty–in Any Classroom, USA–parents with thoughts laden with other things, not wanting to be blamed, not wanting to engage. Betty shows her inability to cope with the emotional fortitude it takes to be a mother, a nurturer, as she herself is unable to deal with the death of her parent. She is a child-mother who needs her own coddling. "Sally needs attention," pleads Miss Farrell when Betty leaves for the ladies room, upset. "There is a very special pain to losing someone at that age. I don't know if you can understand that," She tells Don. "I can," he answers.

Later she calls Don at home and confesses her father dies when she was eight. Her vulnerability intrigues Don:

Showing us he's still a cad at heart, and that even though the things that catch his eye are "pure," his eye still wanders.

The Sterling Cooper office was pretty boring this week, though we did get a glimpse of the British CFO cracking down on the Creative Department's spending, signaling perhaps the end of an era. He cast disapproval not once, but twice, on the habit of drinking in the office. I'm not sure how Roger Sterling would feel about that, since he mixes even his milk with vodka. But even though his names on the wall, Roger might not have much say over a shifting way of doing things. The writers keep remining us: times they are a-changin'.

Besides Sally's apparent interest in the murder of Medgar Evers, who's also mentioned in the office and then later appears in one of Betty's Demerol addled labor-dreams, Pete Campbell is given the Admiral Television account. His take–after talking to Hollis, the black elevator operator–is to market Admiral's products directly to African Americans, since it seems they are already buying them. On an even larger scale, we are reminded, times are changing. The face of America is changing and the civil rights movement is in its adolescence. Admiral hates Pete's pitch, but after a brief flogging from Roger ("It's never as good as you think it's going to be"), Pete is somewhat congratulated for his "risky" idea, after he's called "Martin Luther King" dirisivly by Burt Cooper. The writer's are really hammering home the "change is near," thing this season. As they responsibly should.

Pete was further reminded of his "risk-taking" qualities when Duck Phillips, former Sterling Cooper head of accounts invites him out to lunch to recruite him. Thing is, he's also invited Peggy.

Duck assumes the two have a secret relationship. He's kind of right. Pete did impregnate Peggy in season one, and Peggy gave the baby up for adoption. Later, he propositioned her with an affair. She replied by telling him about the baby, that she could have had him if she wanted. "I could have shamed you into being with me," she said. But Peggy didn't do that.

Her presence seems a sore spot to Pete in any context. She's a constant reminder that his world is fragile, yet he still treats her with disdain. He could spill the beans on her, too.

Duck's brought them there to bring them to his new agency. Peggy is intrigued: "Do we have to go together?" Pete is insulted: "If you want to woe me, you'll have to buy me my own lunch." But even after Pete leaves, Duck is still interested in Peggy, who seems to have lost some of the confidence she gained in the last few episodes. "You're a free-wheelin career girl with smart ideas," Duck tells her. "Am I?" she asks.

Peggy and my affection for her aside, the real star of this episode was Betty, who I haven't been liking very much lately. The reason I haven't been liking her is because I know she's all a facade and she knows she's all a facade, but she doesn't do anything about it, nor does she show an interest in doing anything about it, even though she's miserable. In season one, there was a little bit of a glimpse of awarness in her, but all evidence of that has been absent for many episodes.

Betty goes into labor this week, and the ensuing scenes are a tribute to "modern" medicines treatment of pregnancy like it is a disease (like malaria), instead of a natural occurance (like puberty), and treatment of pregnant women like they are hysterical (as in crazy), instead of in great pain (as in big thing coming out of little hole). "You're job's done," the nurse tells Don, almost with a chuckle, as if congratulating him for ejaculating so well. She wheels Betty away, and she looks back at Don, who's gone as fast as can be. This is not an experience they will share, and nobody thinks it should be.

Later Betty fills out paperwork in a wheelchair, further signaling her "invalid" state. The nurse asks her what she had for lunch. "What were you thinking?" she exclaims when Betty says, "pineapple." I didn't know why this line was here, but I looked it up and apparently it was thought of as an abortifacient. Of couse now we know that's not true. But Betty might have thought it was.

The nurse later dopes her up, and the Lynchiness ensues. This image–the nurse leaning over Betty's bed, looking grotesque and two dimentional, an imitation of herself, back lit by harsh white light–could be a still from an episode of Twin Peaks:

As Betty drifts off into sleep, she hears/imagines the nurse speaking to her as one would a child: "Sit back. You're at five centimeters. That's half way from here to the Hebrides and other mountain ranges, which we are currently studying in chapter twelve. The doctor will be here and there." "The Hebrides are islands," Betty is able to snap back before she's completely in La-La land. She's right.

Later on, in another room that looks like an OR (even though, again, she's just having a baby and there's no mention of a C-section), Betty says, "I can't do it." "Either you can do it or we will, but it's gonna come out some way," responds the nurse, but Betty's not talking about the baby. She's talking about her life, her role. She's unprepared even for the expected task of being a mother. Plus, she doesn't like it very much. She drifts off, dreams she's walking down the hospital hallway to serene music, and finds herself at home in her kitchen. Her father's there, mopping up blood, or rather, mopping down blood:

"Am I dying?" she asks her father. "Ask your mother," he answers, and Betty turns to see her long dead mother, standing with her hands on the shoulders of a bleeding man in a suit, presumably a wounded Medgar Evers:

Betty's mother holds up a hankerchief soaked in blood. "Shut your mouth, you'll catch flies," she says in response to Betty's surprised expression, further cementing Betty's childlike state. "I left my lunch pail on the bus," Betty says, "and I'm having a baby." She sounds scared, like she's in trouble, like she doesn't know what to do. Betty's mother shakes the hankerchief at Betty. "You see what happens to people who speak up?" she asks. "Be happy with what you have." "You're a house cat," her father reassures her, "you're very important and you have little to do." She wakes up with a baby in her arms, looking like she doesn't know how it got there.

Meanwhile, Don's in the waiting room where he meets a prison guard with a Jersey accent named Dennis. The two bond over scotch.

Dennis is the stranger in this episode with whom Don shares more emotion than he does anyone else in his life. This, too, is a reoccurance in the show. They find common ground in their self-disappointment. Dennis swears to Don he'll be a better man when the baby comes. Don confides in Dennis when he tells him he doesn't throw the ball around enough with his son. "Our worst fears lie in anticipation," Don assures Dennis when he says, "If something happens to her I just don't know what I'd do. And then that baby, how could I love that baby."

But it seems Don is wrong. As he strolls down the hallway to get Betty to bring home, he passes Dennis. Dennis is pushing a woman in a wheel chair. There is no baby. He looks away when Dod nods his head in greeting. Perhaps Dennis' worst fear was one he hadn't thought of: a life where he and his wife move into the future with the tragedy of a potential child, a baby who lived for a few hours before expiring. Dennis had expressed some concern over screwing the kid up. Now he won't even have the chance.

Don does pay Sally some of that attention Miss Farrell suggested she needs. In the midst of frying up something that looks like sloppy joe mix and scrabled eggs in the middle of the night, Sally comes down to the kitchen. He asks her if she wants some. "Is the baby gonna live in Grampa Gene's room?" Sally asks. "It's not Grampa Gene's room," explains Don, "It's the baby's room. Everything's gonna be fine." He sounds like he means it.

And he still sounds like he means it when he says it to Peggy in the next scene. She's come to him for a raise, in light of Duck's encouraging offer. Don tells her it's a bad time. And then he says, "You're gonna be fine." "What do you want me to do?" he asks when she implies that this isn't enough. "I don't know how I could have been any clearer," she says. She leaves his office without the fight she wanted, without the result she came for. But she leaves saying, "What if this is my time?"

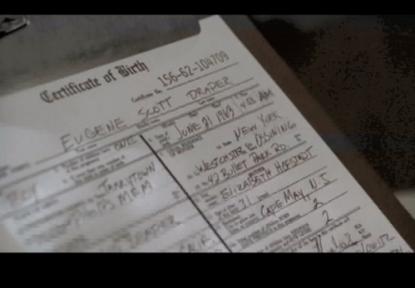

Our time with Peggy this week was brief, but pregnant. Equally pregnant in importance was Betty in her un-pregnantifying. She named her new son Eugene, after her father (as if Sally wasn't confused enough.)

We're reminded once again, by this birth certificate, of Betty's own name, her childhood name. But she must shed this childhood image of herself. She must detatch herself from her subconsious attachment to her parents. The episode ends with Betty walking groggily down a hallway, as she did earlier in her dreamstate. The same serene music plays. But this time she's been waken in the middle of the night by her crying baby and must tend to him (with a bottle, no doubt, since she told the nurse she would not breastfeed). She pauses for a moment and resigns to move forward. She must. She's chosen this path.

We're left with the final image of Betty begrudgingly trudging down the path she's chosen and with Peggy at a crossroads. The two women could not be more different, but their plights are connected to the whimsy of the same man. Peggy might have to make her move soon, as we're teased with more office politics in next week's trailer. It seems the beancounter's agenda might shake things up more than we expect. I have a feeling Roger's going to get the boot, since we see him saying "It's my company, what do I have to worry about." Hint: in horror movies and cliff hangers, those who seem the most confident always die.