Although he's been dutiful (as much as he could be) Don Draper finally broke this week, in the episode called "The Wee Small Hours." And, indeed, much happened in the hours between midnight and morning in this episode, or in small, dark rooms. By putting a large part of the important action in those small hours and spaces, the writers succeeded in taking advantage of a weird, real life phenomenon–things that occur when no one else is awake (or looking) often seem like they themselves are dreams, and can, therefore, be ignored. In other word, it only happens if you get caught.

The episode starts inside a dream. Betty is reclining on her fainting couch, the purchase of which was inspired by Henry Francis. She's being slowly undressed by a man who's face we cannot see. When we do catch a glimpse of his face, it's clear that this is Henry, not Don:

Betty's fantasies are clear, and they have been building since last week. Betty had cheated on Don before, an act that was borne out of his infidelities, but her indiscretion was quick and emotionless in a bar bathroom. It was tawdry. With Henry, she imagines something more tender, something soft and emotional. Something Don (or her father for that matter) never provided for hrt. Her time in Rome with Don only served to exacerbate her unhappiness when they returned, and her fantasies, it seems, have flared up. Now she spends her nights (and the thoughts she cannot control) devoted to a man she has met only three times.

Her dream ends abruptly as she is jolted back to reality. Connie's been calling Don late at night. Betty is jerked out of her sleep to the sound of the telephone and the newborn crying. This is her life. It is full of disappointments.

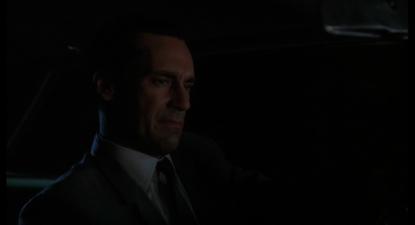

Don's bummed as well. The contract he signed with Sterling Cooper came out of an insistance from Connie Hilton's lawyers. Though Don did end up signing the contract, he did so begrudgingly, and only after a dark, spiraling-out-of-control night with a couple of beatnik hitchhikers who beat him up. He saw an alternative that was not appealing, so he signed. Now, being at the beck and call of someone much more powerful than he is, Don is let down by his current situation:

We see almost this exact same shot (Don sitting on the edge of the bed, head in hand, Betty behind him) later on in the episode after Connie has rejected his ad campaign on the grounds that Don did not give him the moon:

In grand Mad Men tradition, the writers have flanked the action (and named the episode) in the light that they wish to cast it. It starts with Betty's dream, moves to Don on the bed, and goes on to split into a dozen wee hours in small rooms. The action in this episode is dark and hidden, embarassing and inadequate.

Before we really get into the loves and lives of Betty and Don, it's important to look at a character who's merely been a supporting one in the series so far. The first episode of this season drew attention to Sal and his latent homosexuality, and also to Don's awareness of it. That was brought to light in a dark room when Sal was cornered by the bellhop on the business trip he and Don went on together. Had Sal not been caught by Don, who was going past his room on the fire escape, the incident would have occured and Sal would go on to live his life as if it had never happened. But it did happen, because Sal was caught. Sal's homosexuality has been largely unaddressed since, except for a few reminders here and there. But in this episode, the impossibility of living among "normal" people and pretending to be one of them proved impossible for Sal, and it's all due tosomething else that happened in a dark room.

Lee Garner Jr., son of a Lucky Strike magnate, is "a bully," in the truest sense of the term. He hedges in on Sal's directing responsibilities during the commercial shoot for the cigarettes. "Here, look through the camera," offers Sal, giving up the insrument of his power. "That's a good idea," says Lee, and he leans in to look through the lens.

Lee's stance at the camera is reminiscent of the pose a sniper would take (are the writers reminding us again of the imminent assasination of JFK?). And Lee effectively picks off Sal after he rejects the advances made on him in the dark room. Lee calls Harry Crane and tells him to get rid of Sal. Harry doesn't. Lee is angry. Sterling fires Sal and tells Don to fix it. Don's knowledge of what happened in that first dark room decides Sal's fate.

While it is well within Don's power to save Sal's job ("I can stay away from Lucky Strike," says Sal, "lay low from Roger for a day or two, I think it will blow over"). He doesn't. Instead he expresses disgust and intolerance:

“You must have been really shocked," Don says in a sarcastic and biting tone. Sal doesn't quite pick up on it, "I was, believe me.” "But nothing happened. Because nothing could have happened because you’re married," Don responds, knowingly. Sal gets it this time," Don I swear on my mother’s life." "You sure you wanna do thar? Who do you think you’re talking to?" Don asks. It's as if Sal feels cornered again, "I guess I was just supposed to do whatever he wanted? What if it was some girl? "That would depend on what kind of girl it was and what I knew about her," says Don. "You people," he sets Sal as an Other, someone who couldn't possibly operate on the same level as Don, a man with sexual power and prowess–specifically with women. "I think you know that this is the way it has to be," says Don as he turns Sal out. At least he shakes his hand.

Later on, in the wee hours, Sal calls his wife from a telephone booth to tell her he won't be coming home because he's working late. In the background, we can tell that he's in Central Park, most likely the Ramble:

Sal's quickly fallen from his situation at Sterling Cooper where he was continuing his career as a commercial director, something he seemed to enjoy and be really good at, to lurking in the dark, wee hours in a part of the gay culture that, even by todays standard among gays, is looked at at seemly.

The integrity of Don and Betty's characters are held up beside each other in this episode. Their opinions and actions are held up as a veritable compare and contrast. What are they willing to do in the name of infidelity? In the name of civil rights?

The manhood that so allowed Don to strike a harsh judgement of Sal has been questioned by his virtual enslavement to Connie. At once, whenever Connie calls, Don gets up, gets out of bed and leaves the house. He does this in the name of affection, it turns out. "In some ways, you're more than a son to me," Connie tells Don, "because ou didn't have what they had." "Thank you," says Don, "I mean it."

On the way to one of his late night/ early morning summons, Don sees Ms. Farrell jogging along the side of the road. The young school teacher pretty much fits the bill of Don Draper's mistress; she's talky, savvy, thoughtful, and not blond–pretty much everything Betty isn't.

When she accepts a ride from Don, he reaches over to turn off the radio. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream Speech had just started playing.

"Don't," says Ms. Farrell, and stops him. This is what she looked like when she was listening to the speech:

This is what Don looked like:

Pretty cut and dry. The speech, like Sal, disgusts Don. And it doesn't disgust him because he's racist, just as Sal doesn't disgust him because he has sex with men. In both cases, the element that is so vile to Don is the expression of fallibility, and the acknowledgement that everyone is the same. Because if that is the case, then there is no need for a facade. And what is Don Draper, the man, the ad man, the husband, than a facade. He's bought into the character he's been playing, and doesn't quite know a new way to spin it.

Betty, on the other had, brushes off Civil Rights with an extreme portrayal of ignorance. Standing in the kitchen with Carla, her black maid, Martin Luther King Jr. again plays on the radio. This time, he's speaking at the funeral of the four girls who were killed in the Birmingham church bombing. Again, we are grounded in reality by a real event that seems surreal, impossible even. "It's so horrifying," Betty says to Carla. "I hate to say this," she continues, "but it's really made me wonder about Civil Rights. Maybe it's not supposed to happen right now." Her expression is not one of disgust, but of sheer and perhaps purposeful misunderstanding. Socially, it is important for her to seem progressive. But she does employ a black maid (whom she calls "my girl"). The Civil Rights movement not moving forward would benefit Betty. Whether or not she is conscious of this is to be determined.

In both cases, Betty and Don's ultimate opposition to Civil Rights come from places rife with subtle shades of gray. Their infidelitious actions are not so subtle.

Don's initial drivie with Ms. Farrell resulted in the discovery about where she lived. She turned him down in that scene, but she dropped crumbs for him, letting him know where she lived, and flirting with him. The dialogue leaves the door wide open for Don to return later:

Don: It’s a nice hosue.

Ms. Farrell: I rent the apartment over the garage.

Don: Have coffee with me.

Ms. Farrell: You’ll be late for work.

Don: I’m always late. It’s coffee.

Ms. Farrell: Uh huh. Maybe that’s why you can’t sleep. Too much coffee.

She knows what he really wants, and it certainly isn't coffee. And she tells him exactlty where to find her. So later on, when he shows up at her door, she doesn't seem that surprised. He's agressive with her: "So let me in." She's practical: "I know exactly how it ends," she says. "I don't think you've done this before this way," insinuating that perhaps she has. "I don't care," says Don. "I want you. Doesn't that mean anything to someone like you?" He casts her in the Other category. But this time, instead of being disgusted, he's bewildered. "What are you, dumb or pure?" he asked her earlier in the episode. He can't get a handle on her, so he needs to figure her out. He thought he had Connie figured out, thought that Connie loved him. Don's been following Connie around like a dog for weeks. Now, after being rejected, he seeks power over someone else, as well as affection that he can take or leave. I'm disappointed in Ms. Farrell for giving in.

Betty's would-be affair with Henry ends before it begins. She, like Don, drives over to him and confronts him in his office. She initiated contact with by writing him a letter in which she said, "I do have thoughts." This is a loaded line, one that drives Henry mad with desire for her. At his office, he points out that she needed to come to him, because she's married. She has no experience with this, and when Henry points out the inevitable nature of affairs–quickies on the sofa, pay-by-the-hour motels–Betty is suddenly turned off. "I don't know what you want," Henry tells her. It's something we've heard Don say to her a million times, and comes from her childlike, black and white expectations. And Betty doesn't quite know what she wants, either. But she saw something in Henry–something like emotion or tenderness. And it's this that she wants, not another "tawdry" encounter.