I apoligize that this post is a couple of days later than usual. It's due to a little essay published in the latest issue of The Atlantic. Ben Schwartz, that magazine's literary editor and national editor (telling titles for the way he approaches this piece), purports to reveal "What's wrong—and what's gloriously right—with AMC's hit show." Schwartz is able to sum up, in a word coined by film critic David Canby, what makes mad men part of a fairly new (it began with The Sopranos) genre of storytelling. These "weekly dramas" are unlike other shows that would fall under that category, like, say, Law and Order or The OC. Shows like The Sopranos, Deadwood, The Wire, and Mad Men are in a class of their own. These shows are "megamovies." And like movies, they should be watched, says Schwartz, all at once, marathon style, if the viewer is really going to take in all of their nuance and dramatic development. (Interestingly, all other megamovies mentioned here were produced by HBO, who turned down Mad Men before AMC picked it up.)

So perhaps it is because I have to wait a whole six days between episodes, and spend at least half of those days thinking closely about the show, I found this week's episode to be a little boring. Week after week, for practically the entire season, the writers of Mad Men have been dropping the same hints: referencing the fall of Rome, the uncertainty of Sterling Cooper's future, potential threats to the delicate facade Don has built up for himself. All things point to some explosive event. Something is going to happen that will change everything for good. Something that will end the era of tall men in suits and blond women in trussed undergarments, bosses and secretaries, white housewives and black maids. At the time of this episode, the civil rights movement is in full swing, the second wave of Feminism is about to hit, and November 22 is right around the corner. "Enjoy the world as it is, Margaret," Roger Sterling's mother says to his young wife Jane, mistaking her for his daughter. "They'll change it and never give you a reason."

Okay. We get it. The, "soup's about to hit the fan," (as Bert Cooper would put it). Start spraying us in the face with hot broth and potatoes already.

But that's not how a responsible megamovie behaves, I bet Canby would say (though there were enough gunfire and boobs in every episode of The Sopranos to keep viewers on their toes.) But I would argue that Mad Men has been teasing us for far too long, the writers have dropped a sufficient amount of crumbs, and the episodes have gotten increasingly sleepy (kind of like they did when Don did a stint in California last season). But the slowed down pace of an already slow and deliberate show has, at least, given us a chance to look even more closely at the character development. And, just as Schwartz was able to start seeing flaws left and right as he watched all of the episodes in a row (26 hours and counting), watching closely will bring out the flaws in an episode—or in a show overall.

This week, Don and Betty got back to their old ways. Or rather, Don brought them back. It seems that theirs is a marriage that has from the beginning been all for show, like the identity of Don Draper himself. Don continues to seek affection from other women. Every affair he's had has been with a woman who is completely unlike Betty, the biggest indicator to this being a visual one: their hair color. Of the affairs we've seen, Don's been with three brunettes and one redhead. In these past affairs, Don's found himself with women who were powerful, intellectual, rich, and/or influential…other ways they were different from Betty. This time, he's sought out a nurturer. Being a warm, nurturing mother doesn't come naturally to Betty, even though she has three children. We get the impression she had them because it was the thing to do. Don's found a mother without a child in Miss Farrell (though she surrounds herself with children every day), and has inserted himself into her world.

He's smiling in this shot. And a Don Draper smile is hard to come by, Lane Pryce points out when Don receives his $5,000 bonus (what would that be equivalent to now, $34,800?). Miss Farrell seems to remind him of his past, with her meager apartment and long hair and homemade dresses. She's not someone Don Draper would be able to show off, but someone Dick Whitman would like. "I would have liked you," he says, when she asks him what he was like as a child.

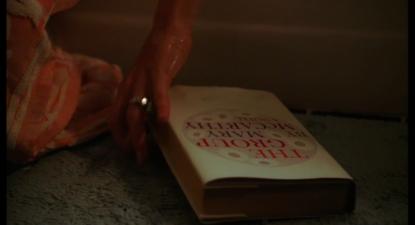

Betty, on the other hand, is trudging through a way to understand her position in the world. But instead of just fumbling around the house and tearing apart Don's things, or manipulating a friend into an affair, she's reading The Group by Mary McCarthy, a satire about the lives of disillusioned, upper-middle-class American women:

The book hit the New York Times best seller list in 1963, so it's likely that a woman like Betty with all of her social concerns would read the book, if for no other reason than to keep up appearances. But something about her episode-long absorption in the book implied that she was not simply reading this book because she was supposed to, but that she was really getting into it, and perhaps drawing parallels from it to her own life. This is uncharacteristic of Betty.

Her character has been in a state of flux this season; we've seen her go from pretty but simple housewife to woman-of-the-world to a scheming would-be adulterer to a little girl trapped in a woman's body to the brink of rebelliousness. This would be fine if the suggestion is that her character is growing or changing, but Schwartz points out that the writers included the detail, a few episodes back, that Betty attended Bryn Mawr. And Betty, it was established in the first season, was a sorority girl. Bryn Mawr has never had sororities. In a show, a costume drama, really, that pays such close attention to detail, and one that is a member of the megamovie genre, whose storyline and narrative arc must have continuity, such a slip up is inexcusable.

Another such slip-up, or rather, improbability, jumped out at me in this episode. Let's, for a moment, skip over the scenario between Peggy and Kinsey that was loaded with sexual tension, even though its analysis is more pertinent to the subject matter of this blog. Let's take a look at the "realism" that is presented to us in Mad Men.

Don shows up at Miss Farrell's apartment after she corners him on the train. Her epileptic brother is still there. She's gotten him a job at the VA hospital in Bedford, Mass. Don offers to drive him there. It's dark outside, and it's late September or early October (Don get's his signing bonus earlier in the episode and questions why it took two months. He signed his contract on July 23). So daylight savings hasn't yet happened. It's got to at least six, probably more like seven, considering the long day Don had at work and the commute. So say they leave at seven and head to Bedford from Ossining. They'd take 84, right? The drive would be about three hours… that would get him back a little after one a.m. Except 84 wasn't finished until 1971. Okay. Then Don would have taken 95, which would have tacked about half an hour onto the drive. So he'd get back around two a.m.

Don and Danny (Miss Farrell's brother) have one of those classic Don Draper conversations, where Don reveals something of himself to someone he thinks he'll never see again. Danny explains how he's afflicted, how he can't pull himself up by his boot straps. He explains that he's not lacking intelligence by telling Don that, "Julius Ceasar had epilepsy. He ran Rome." "Things didn't turn out to well for him," Don responds. Not only have the writers managed to convince me that the only reason Danny was introduced was simply to drop the fact about Ceasar and remind us of the fallen city, which has been mentioned at least once in every episode since Sally and Gene's reading sessions, but by doing so, inadvertantly pointed out the absurdity of the escapade that Don undertook. Don pulls over to let Danny out, "twenty miles outside of Framingham." Why would they be outside of Framingham, a city west of Bedford, if they were coming from the south? It would have made more sense for Don to have said, "twenty miles outside of Boston," or "Newton." But, as we see from this shot:

Don is on route 20. And don't think it's not on purpose. The sign is the only thing other than the headlights of the car that is visible in the shot (it's hard to see here, but when watching it on TV, the sign in the upper-right quadrant of the shot is clear). If Don were to take a route from Ossining to Bedford that would have put him on 20E, he would have had to go this way, a trip that would take almost six hours, one way. This would have put him back in Ossining, and at Miss Farrell's apartment, at seven a.m. It was still dark when he got back.

Sure, it's a television show. Sure, it's fiction. But not only is it a costume drama, as Schwartz claims, but it is historical fiction. We are reminded at every turn of real events, we are shown accurate costumes; we are given images of magazines, typewriters, gloves, shoes, girdles, an endless stream of products that would be considered relics today. So if we are to buy the accuracy of the things we see, mustn't we expect the same consistency in the storyline?

Schwartz's piece really threw a wrench in how I think about this show. He didn't say anything that I wasn't already figuring out, but he said it really well. Of course the show isn't just showing us racism and sexism as it was. It is overtly condemning it. Case in point: Kinsey vs. Peggy.

Kinsey pitches an idea to Don. Don dismisses it due to the fact that it's too complicated (read: insufferably long-winded, like Kinsey himself). Peggy tweaks Kinsey's idea, puts, "her little spin on it." Kinsey is pissed:

And later confronts Peggy in her office. "Wearing a dress isn't going to help you with Western Union. You do your work and I'll do mine. Let the chips fall where they may."

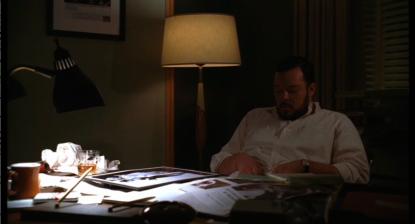

So that night, the two copywriters are in their respective offices, each one doing their own work. Peggy is dilligently brainstorming. Kinsey is doing this:

In case you can't tell, he's getting ready to masturbate while simultaniously getting wasted. Miraculously, he comes up with a brilliant idea. But instead of writing it down, he drinks more to congratulate himself. He forgets the idea in the morning.

Before they present the idea to Don, Peggy stops by Kinsey's office. The dialogue that follows clearly shows where the writers affections are. Notice how her predictions come true when Don empathizes with Kinsey. Notice how she still manages to put her spin on Kinsey's idea, even though he didn't realize he had it. Notice how Kinsey's education (his knowledge of the Chinese proverb) does not compete with Peggy's natural wit and inelligence (her interpretation of the "Chinese thing"):

Kinsey: I've got nothing.

Peggy: What a relief, mine's garbage, too.

Kinsey: No, I had something. Something incredible. But I lost it. I didn't write it down.

Peggy: Oh, I hate that.

Kinsey: It might have been the best idea I ever had. I did everything. I talked to Achillies. I spent last night recreating every detail of the evening hoping it would come back. You know how it is. There was nothing and then there was it and now it's nothing again.

Peggy: How do you talk to Achilles?

Kinsey: He's a janitor with a very bad memory. You know what the Chinese say? The faintest ink is better than the best memory.

Peggy: Come on. We've failed before.

[They go to Don's office.]

Peggy: Okay. We really looked for advantages. One of them is phone calls happen every day. A telegram's a big deal. Something like: "She's getting married. Are you really just going to give her a call?"[…]Don: What do you have?

Kinsey: Mine aren't any better.

Don: Damn it, Kinsey. What's your excuse? Peggy: Don't yell at him.

Don: Excuse me?

Peggy: Tell him what happened.

Kinsey: No. The dog ate my homework. I had a great idea and I lost it. I didn't write it down.

Don: I hate when that happens.

Peggy: I keep thinking about that Chinese thing you said. What was it?

Kinsey: The faintest ink is better than the best memory?

Peggy: It just makes me think: You call someone on the phone, 'hello I'm getting married,' or 'congratulations on the baby,' and then you hang up. It's gone. Poof. It's different if you send a telegram. A telegram is permanent. Something like: 'A telegram is forever.'

Don: You can't frame a phone call.

Kinsey: My god.

Don: That's the way to go. You two work on that.

It's almost certain that, if the roles were reversed, and it were Peggy who came to the meeting with nothing, Kinsey would have gloated and tried to cast her in a negative light in Don's eyes. Similarly, it could have been easy for Peggy to do this to Kinsey, since he attacked her earlier, but not smart. She would have created an enemy. This exchange is so clearly swayed in Peggy's favor that there is no question about the writer's motives and the moral they intended: sexism happened, this is what it looked like, it was bad. It's a safe message, because it's one that society has already determined to be true. But the writers go even further. In this case, Peggy was helped by being a woman. Men are boorish, pompus, over-educated drinkers. Women, or at least, Peggy, have been met with challenges and are mature, level-headed and more responsible.

I'll be watching through a slightly different lens than I did before I read Schwartz's essay. And part of me feels a 26+ hour marathon coming on. Though I have a feeling that, as a megamovie, Mad Men's inconsistencies will be glaring, and I will lose the awesome admiration I have for it