This essay addresses working and economic conditions in Holyoke during the 1870s and 1880s as the city acquired industrial stature and some paper and textile workers attempted to organize. But it starts from the perspective of a paper maker who experienced the final collapse of the city’s industrial base in the 1950s and 1960s and presided over the oldest surviving labor organization in Holyoke.

Ray Beaudry learned his papermaking skills in the early 1950s under the traditional tutelage of a machine tender who headed the local Papermaker’s Union. Ray survived that decade’s job losses and foresaw the disappearance of the paper industry in Holyoke. By the mid-1960s he had succeeded his mentor as President of Eagle Lodge Local One and watched nearly all of Holyoke’s paper plants shut down. Ray’s union, the International Brotherhood of Paper Makers, traced its roots to the formation by Holyoke machine tenders and beater engineers of the Eagle Lodge, chartered in 1884.

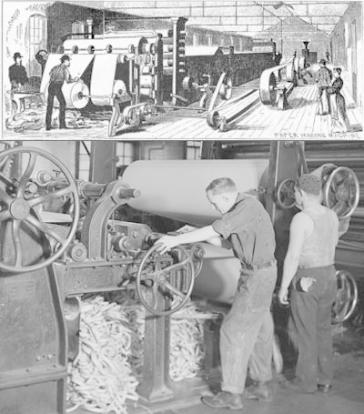

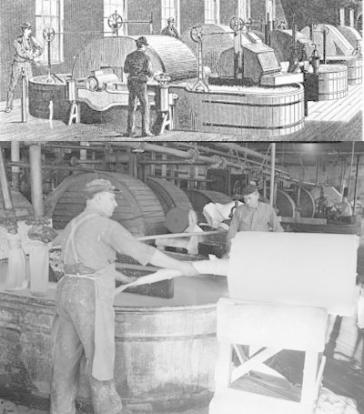

Machine tenders traditionally held an elevated and powerful role in the labor force. They hired their crews, negotiated with management and often progressed to superintendent. Ray Beaudry commented in a 1988 interview for the “Shifting Gears” project at Holyoke Heritage State Park, “When I started in the paper industry, it was still, you know, it was a trade… In the early days of machine tending in Holyoke, it would take you sometimes maybe fifteen, twenty years to get to that position.” As labor leaders they represented the interests of the skilled, male-dominated elite and showed no eagerness to include lower-ranked paper workers such as the women in the rag and finishing rooms.

Some background on Holyoke’s paper and textile industries in the 1870s and 1880s explains the barriers facing labor organization in those early days and the relatively strong position of skilled paper workers.

The new dam and expanding canal system attracted textile and paper mills in the early 1850s. Capital flowed into the city between the end of the Civil War and the Panic of 1873. But the labor force, swelling with immigrants, lacked leverage with employers. Many immigrants considered their living and employment conditions to be at least better than those they had escaped. Workers relied for their welfare on the paternalistic care provided by employers, designed to ensure the loyalty of workers and prevent labor agitation.

Wage reductions in the textile mills in the mid-1870s sparked a short-lived and unsuccessful strike by weavers and spinners. Statewide political pressure and exposure of factory conditions led to legislation in 1874 limiting the work week to sixty hours for women and children textile workers under age eighteen, which effectively reduced the work week for all textile workers. As the economy recovered, wages ros e and construction boomed in the late 1870s and early 1880s. Craftsmen in the building trades, seeking to control the labor market, took some successful actions. (See footnote 1.) Textile workers, however, remained largely unorganized. Some who walked out gained raises, while others were fired and replaced.

e and construction boomed in the late 1870s and early 1880s. Craftsmen in the building trades, seeking to control the labor market, took some successful actions. (See footnote 1.) Textile workers, however, remained largely unorganized. Some who walked out gained raises, while others were fired and replaced.

Immigrants from Quebec, willing to work for lower wages, flooded the labor market in the late 1870s. They sparked ethnic frictions and added to language barriers that fractured the workforce. These French Canadians, drawn away from a depressed agricultural economy by advertisements of jobs in Holyoke, soon dominated the textile labor force. The newcomers faced resentment and disdain, especially from Irish feeling threatened in lower-skilled textile jobs.

During the 1870s the population of Holyoke doubled (to 22,000 in 1880) and contained the highest proportion of foreign-born residents of any city in Massachusetts – about half throughout the 1870s. (See footnote 2.) Throughout the decade about 42% of the foreign-born came from Ireland or Canada, but the balance between these two ethnic groups shifted toward Canadian origin. The French Canadian population was sixty percent of the Irish population in 1870; by 1880 French Canadians numbered almost 5000, exceeding the Irish by sixteen percent. Of the native-born half in 1880, sixty percent had foreign-born parents. (See footnote 3.) Native-born household heads in 1880 held non-manual jobs at a far higher rate (34%) than Irish at 8% or Canadian at 6%. (See footnote 4.)

Even the Massachusetts Bureau of Labor Statistics took a dim view of French Canadian immigrants in 1881. Its twelfth annual report charged, “They care nothing for our institutions, civil, political or educational… They are a horde of industrial invaders, not a stream of stable settlers… These people have one good trait. They are indefatigable workers, and docile… Now it is not strange that so sordid and low a people should awaken corresponding feelings in the managers, and that these should feel that, the longer the hours for such people, the better, and that to work them to the uttermost is about the only good use they can be put to…” The Holyoke Transcript, a newspaper generally sympathetic to the managerial stance, joined the public outcry and rose to the defense of the French-Canadian community. (See footnote 5.) Ethnic groups settled in distinct communities and worked in clusters in the mills, hindering their association by trade. Louis Gendron, a paper worker at National Blank Book during the 1950s, commented in a “Shifting Gears” interview in 1988 on the hiring practices and ethnic enclaves of workers in earlier days. “Way back in the beginning it was quite a family affair… They would sometimes go as many as three generations working there. There was a lot of that, not towards the end, because of the diversification of people and the different kind of jobs that were open.”

Holyoke’s paper industry led the nation in sales, but was buffeted by economic booms and busts. Faster machines and more manufacturers entering the market caused overproduction and periodic shutdowns. Competition arose from cheaper pulp paper made in more heavily forested places such as Wisconsin and Canada. The price of fine writing paper fell by 58% between 1865 and 1880. (See footnote 6.) Four new mills built in the early 1880s generated a boom, but then led to overproduction and depression in the mid-1880s. After recovery Holyoke produced 80% of the nation’s fine writing and bond papers in 1890.

The Paper Makers Protective Union formed in 1874 – in the wake of the 1873 panic – as the first paper industry’s trade association to provide sickness, injury and unemployment benefits. The Protective Union dissolved within three years, pressured by mill closings and an influx of immigrant and migratory “tramp” labor.

The Paper Makers Protective Union formed in 1874 – in the wake of the 1873 panic – as the first paper industry’s trade association to provide sickness, injury and unemployment benefits. The Protective Union dissolved within three years, pressured by mill closings and an influx of immigrant and migratory “tramp” labor.

Eagle Lodge, founded in reaction to the depression of 1884-85, sought primarily to reduce the long hours in the paper industry’s two-tour system. Typically papermaking machines ran around the clock. Laborers in this two-tour system worked eleven-hour days and thirteen-hour nights on alternating weeks. Eagle Lodge stimulated discussion in Holyoke and took their case to the convention of American Paper Manufacturers at Saratoga in 1886. Whiting Paper responded by reducing the machine tenders’ workweek from 72 to 60 hours. Whiting’s backtenders (one step below machine tender) took a 15 percent pay increase rather than a shorter week.

But Eagle Lodge failed to make much headway in most of the paper mills. Wages remained low relative to profits in the paper industry, even as it boomed in the late 1880s. Mill owners refused to supplant the two-tour system with three shifts until after 1900. Antagonism between workers and management intensified, reflecting a broader erosion of worker’s faith in and reliance upon their employers’ concern for their welfare. Workers were realizing that they would have to take protective action despite their fears.

More radical fringe movements like the German-backed socialists gained little following in 1880s Holyoke. But growing anger set the stage for more militant labor activity after the severe depression of the 1890s lifted and trusts formed under absentee financiers at the close of the century.

Footnotes:

(1) Tom Juravich, William F. Hartford and James R. Green, Commonwealth of Toil: Chapters in the History of Massachusetts Workers and Their Unions, University of Massachusetts Press, 1996

(2) Therese Bilodeau, “The French in Holyoke [1850-1900],” Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. III No. 1, Spring 1974

(3) From Census data collected by Constance McLaughlin Green, Holyoke, Massachusetts: A Case History of the Industrial Revolution in America, Yale University Press, 1939

(4) Myfanwy Morgan and Hilda H. Golden, “Immigrant Families in an Industrial City: A Study of Households in Holyoke, 1880,” Journal of Family History, Spring 1979

(5) Quoted by Marianne Pedulla in “Labor in a City of Immigrants: Holyoke, 1882-1888,” Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. XIII No. 2, June 1985, p.154

(6) Joshua L. Root, “Something Will Drop: Socialists, Unions and Trusts in Nineteenth-Century Holyoke,” Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 37 No. 2, 2009