early in the film:

Mordecai (Billy Curtis): What did you say your name was again?

The Stranger (Clint Eastwood): I didn’t.

Mordecai: No. I guess you didn’t at that, did you?

just before the conclusion:

Mordecai: You know, I never did know your name.

The Stranger: Yes, you do.

—“High Plains Drifter” (1973)

* * *

A celebrity displays bizarre behavior, but blame falls on an out-of-control wife—until the husband admits he was the wrongdoer, apologizes, and takes “full responsibility” for “foolish errors”—though conveniently blaming them on a psychological condition for which he is now receiving treatment. It’s the sort of thing one would expect of, maybe, a professional golfer—not a historian.

The scandal that rocked the British historical profession last month arose from a series of provocative reader reviews on the British Amazon website. On April 12, Rachel Polonsky spotted one that trashed her otherwise well-received book on Russia. Suspicious as well as angry, she set about investigating, and discovered a pattern: the user “Historian” had savaged books by other respected figures in the field but gushed with praise for the work of Orlando Figes alone. After comparing notes with other victims, she charged that the anonymous attacker was none other than Figes, whose book she had once criticized in a review. More dirt came to light: he had tangled with other colleagues who accused him of a casual attitude toward both facts and sources. He responded with denials and harsh threats of legal action against his accusers in both academe and the press. Then, on April 16, Figes announced his discovery that his wife, a lawyer, had written the reviews. Exactly a week later, Figes confessed that he himself was the culprit: studying the crimes of Stalinism had plunged him into clinical depression, and when his authorship of the reviews became known, he panicked, whereupon his wife offered to take the blame out of solicitude for his mental and physical health.

Admittedly, some readers found Polonsky et al. humorless and self-important. (Why, after all, would either Figes or his scholarly competitors think some Amazon reader’s “review” mattered?) Okay, so historians aren’t necessarily the nicest people, but even if we’re nasty, we draw the line at dishonesty. For the general public, the lurid appeal of the morality tale no doubt had to do with the “chutzpah” (or, since this is Britain: cheekiness) factor: What in the world was he thinking? How could he believe he would get away with hiding behind a “sock puppet”?

Much of the commentary focused, however, not on Figes’s comments, but on his misuse of the legal system to prevent fellow historians and the press “from making statements that he knew to be true.” The incident increased calls for a reform of British libel law, which heavily favors the plaintiff. Oxford Sovietologist Robert Service described his fear of losing “house and home” to a lawsuit and decried the “unpleasant personal attacks in the old Soviet fashion.” TLS editor Peter Stothard (another of Figes’s targets) agreed, “There’s nothing new about oversensitive writers and . . . anonymous criticism.” For the Independent’s Philip Hensher, however, that was precisely the point:

With the internet have come huge opportunities for anonymity. Anyone can say what they like about anyone else without there being the slightest risk of an interest, a direct connection, or an obligation being uncovered. . . . . I can see the reason for SalamPax, the famous gay Iraqi blogger, to write pseudonymously. What possibly justification can there be for a blog of book reviews, or the reviews on Amazon, to remain anonymous, unless to conceal improper interests?

With the internet have come huge opportunities for anonymity. Anyone can say what they like about anyone else without there being the slightest risk of an interest, a direct connection, or an obligation being uncovered. . . . . I can see the reason for SalamPax, the famous gay Iraqi blogger, to write pseudonymously. What possibly justification can there be for a blog of book reviews, or the reviews on Amazon, to remain anonymous, unless to conceal improper interests?

Strange as it may seem, this episode, like many aspects of today’s new digital culture, seems very familiar to the historian of print culture in the Enlightenment.

In the mid-1790s, star author Friedrich Schiller was tirelessly promoting his new literary journal. Attempting to browbeat an elder competitor into quitting failed, but declining to reveal until the end of each year which of his celebrated collaborators had written the individual pieces proved to be a shrewd marketing move. By contrast, an under-the-table arrangement for those contributors to review each issue of their own journal anonymously in the leading critical periodical blew up in his face when word leaked out. Schiller ran into trouble because he was working in a time of transition.

Most of us probably assume that identification of authorship should be the norm. It was not always so. Michel Foucault famously posited a fundamental shift in the “author function.” In the Middle Ages, anonymity was not a drawback for a literary work, whose age vouched for its worth, whereas scientific works derived their credibility from their authors’ names. By the Enlightenment, scientific works were judged on their merits, but ascription of authorship became crucial to notions of literary quality. Thus “literary anonymity is not tolerable.” We have to know.

To be sure, we are all familiar with some now-classic works that appeared anonymously or under pseudonyms for reasons of free expression or personal safety: The Federalist or Voltaire’s Candide, for example. And Robert Darnton has made a career of exploring the murky world of underground authorship in that period, showing in particular how political libel and pornography helped to delegitimize the French Old Regime. Yet there were multiple reasons for the persistence of anonymity.

for reasons of free expression or personal safety: The Federalist or Voltaire’s Candide, for example. And Robert Darnton has made a career of exploring the murky world of underground authorship in that period, showing in particular how political libel and pornography helped to delegitimize the French Old Regime. Yet there were multiple reasons for the persistence of anonymity.

In no other period were anonymous and pseudonymous writing so widespread: in reviewing in particular, the rule rather than the exception. Because writing for money was still regarded as crass and few men could live by their pens, many non-academic writers concealed their identities in order to avoid charges of egotism and cupidity as well as obstacles to careers in courtly or civic life. After Schiller, a regimental physician, published and produced a play in 1782, his ruler threw him in jail and forbade him to write. (Didn’t work: he fled the land.) In the course of the nineteenth century, acknowledged authorship and remuneration established themselves as the new norms.

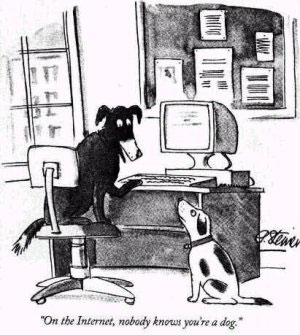

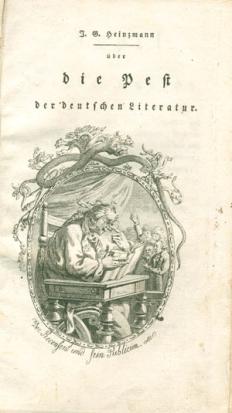

Today, both anonymous and signed work can, depending on context, be seen as guarantees of fairness and high standards. Thus, for example, we expect book reviewers and journalists to identify themselves, yet we prefer blind peer review of manuscript submissions and grant proposals. In other ways, our world again recalls the eighteenth century, with its anxiety over excessive writing and reading—“graphomania” and “reading frenzy”—only there are a lot more of us doing it, and we’re all doing it on the internet. Seventy-one percent of Americans go online daily, where 46 percent participate in social networks (19 percent are on Twitter). Technorati has indexed 133 million blogs generating nearly a million posts a day. As a famous New Yorker cartoon made clear, one of the attractions of the internet is the ability to separate online expression and offline identity. The expectation, still dominant in the print media, that both articles and reader responses should be signed, does not necessarily prevail in the digital realm. Nearly a third of bloggers surveyed say it is important, for personal or professional reasons, that they conceal their identities. Amherst has witnessed contentious debates about both the propriety of blogging by elected officials and “the plague of anonymous rants” in the blogosphere (1, 2, 3). Here, as elsewhere, concern about the increasingly blurred line between uncivil speech and hate speech is mounting. (Anonymous) bloggers have created a site just to keep track of antisemitism on the Guardian’s “Comment is Free” page.

The problem today is that we have not fully resolved our attitude toward anonymity. We use—and regard—it as both a shield and a mask. On the one hand, we look to it as the guarantor of free expression. On the other hand, we fear that some hide behind it in order to abuse that right. We are faced with another paradox: never has it been easier for the average citizen to publicize his or her views, even anonymously and apparently without accountability, and yet, as we leave ever more numerous electronic traces of our views, lives, and tastes, the expectation of privacy may prove to be illusory (1, 2, 3, 4). Orlando Figes’s anonymous activities eventually pointed to his home computer.

One lesson from the affair, which applies to all of us: you can write, but you cannot hide.

Images:

Top: New Yorker Cartoon

Bottom: “The Reviewer and His Public,” caricature of the title page of J.G. Heinzmann, The Plague of German Literature (privately published by the author, Zurich, 1795)