“Don’t apologize, it’s a sign of weakness,” says John Wayne’s Capt. Nathan Brittles to a fresh-faced lieutenant. Men and women I know, who grew up in America, mostly think it a hilarity that exemplifies what they work to change. I take it differently.

In August 1945, WWII ended, Japan surrendered, the “Peace” government of the occupied China broke apart. Officials were rounded up and tried as collaborators and traitors by the winning government. The accused, at the trials, cited Confucian virtues of righteousness and morality, the republican ideals of patriotism and sacrifice, to justify their actions. Then, the judges applied those same values to debase, condemn, and, to execute some of them.

We moved to Shanghai. I was nine, and went to school for the first time – in a classroom, beyond my brothers and a tutor. I took to the big city, but not to the strictures of the school. I lived for Sunday afternoons when we went to the movies.

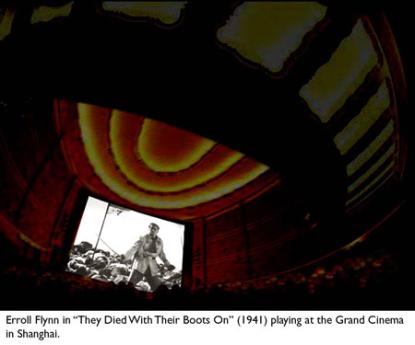

1946, after eight years of privations, peace was finally bursting out all over Shanghai. Movie palaces refitted, neon lights relit, chrome and velour restored to prewar sheen. At first, it was a sprinkling of Soviet films, then compilations of American wartime newsreels which helped erase the instilled Japanese and German propaganda. Then, gloriously, the floodgate opened to seven war-years of stockpiled Hollywood studio products. Half-a-dozen of new, and old, movies every week, major, minor and mediocre: rousing can-do war films, Arabian Night fantasies, historical swashbucklers, literary dramas, bio-pics, musicals, Technicolor Home in Indiana, and the like. But, for me, through ages ten, eleven and twelve, it was the Westerns.

With the abundance, I soon noted the difference between common shoot-‘em-ups and open-spaced sagas. Shanghai was very literary before the war, with many journals and critics. With the new bounty of films, criticism blossomed. I, too, tried to grade films, and then, to rank directors: Ford, Hawks, Raoul Walsh, Henry King, Michael Curtiz…

As I was growing out of boyhood, the society around me was a mix of pretend glory of having won the war, and a veiled shame of having survived the occupation. I scanned the adults. Their culture of hierarchies, obedience and conformity seemed, to me, spent. Their absorbed self-justification did not avail me much guidance. But, the Sunday Hollywood heroes were plenty entertaining and grander than life. And as models, their characters could be mulled over and tried on without much liability.

First up was Errol Flynn as Gen. George Armstrong Custer in Warner Brothers’ They Died With Their Boots On (1941). He played the role with his usual dash, but unlike his heroes of the ‘30s, here, he does not fight for the poor, or, injustice, but for the glory of his own character. His Last Stand death is heroism without cause. Released soon after Pearl Harbor, that heroism might have helped steel the resolve for oncoming battles. Six year later, showing at Shanghai’s art-deco Grand Cinema, its great success was due to its entertainment qualities, rather than its vainglorious end. It was enjoyable to see, but not much for emulation.

A few months later, John Ford’s 1948 Fort Apache opened. It is essentially the Custer story with new after-the-war insights. Col. Thursday (Henry Fonda), arrogant, rigid, disdainful of Indians and his frontier commission, looked for a great battle to achieve his longed-for renown. His subordinate Capt. York (John Wayne), was offered as the inverse: experienced, honorable and respectful of promises to the Apaches. Thursday’s foolhardy charge into what he thought was the Indian camp, was disastrous. The regiment was annihilated. The come-on poster for the film suggested another They Died, with great action-scenes and a Last Stand, backed by flags and guidons. But, in the film that Ford made, the battle was over in less than a minute, shot from a distance, and its elusive glory obscured in a cloud of dust.

For a child on the verge of finding ways to adulthood, it was disconcerting, and ultimately mind-altering: heroism is deathly destructive; justice and tolerance are personal responsibilities.

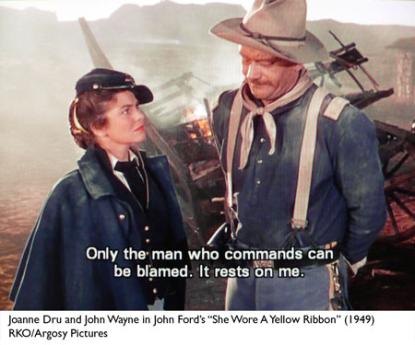

Ford’s next cavalry picture, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, made these qualities even more central. The actions in the film were very minor: it was about cycles of life, people and horses traversing the landscape, and accountability in not placing blames or making excuses.

As Yellow Ribbon was being filmed in Monument Valley during the fall of 1948, the Communists were winning the civil war in China. My family packed, and soon we left Shanghai. I think I might have missed the cinemas as much as our home. At the rail of the freighter taking us to Hong Kong, my brother and I wondered if we were to see any of those movies in production that we had been tracking for months, especially Howard Hawks’ Red River and Ford’s Yellow Ribbon. But, Hollywood, of course, was everywhere. A year later, we arrived in Paris: there were cinemas, and cinemas.

So, we caught Yellow Ribbon at the second-run Ciné Boul’Mich, in the Latin Quarter, as La Charge héroïque, dubbed in French. John Wayne said: “Ne vous excusez jamais! C’est un signe de faiblesse.” I took it to mean (with elementary French comprehension, and a good understanding of Ford’s imagery): if one does not do what is right to start with, apologies would not be of much use afterwards. Or: as our actions are the result of us taking responsibility for ourselves, there is no one else to blame, and no one to apologize to. It was 1950, I turned 14, St.-Germain-des-Prés, where the existentialists roosted, was just around the corner.