The playlist for my mother’s birthday CD, entitled “Attie’s Music,” is dominated by American swing/jazz. I realize these are not the same, but since my mother was born and bred and lives in Holland, let’s start there in contrast to the European music one might expect on her list of faves. The greats all have their place: Ella and Louis, Frank Sinatra and Lena Horne, Doris Day, Glen Miller, Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters. But here’s the catch: they didn’t make the list by way of being who they were. They got on the list because they were the ones who made famous the songs that had to be on the list.

As a child, I loved my mother’s song book as a given—without context or differentiation, without artist or history — these were just her songs: Sentimental Journey, Mack the Knife, Don’t Sit under the Apple Tree (with anyone else but me), Into Each Life (some rain must fall), In the Mood, Stormy Weather. Putting the CD together, considering which versions of the songs were the “right” ones, the ones Attie listened to as a young woman, I realized most of them hail from the World War II era (not that weird: Attie turned 18 in 1945, she was of the age when one’s music taste is formed). In fact, many were recorded during the war years.

The whole thing begged a question I had never asked: where did she get this stuff? My mother spent, as I wrote earlier, her high school years in occupied Holland, where what you might listen to was highly regulated. Jazz was not among the allowed formats. The Nazis saw it as degenerate “African” music. Until 1937, the Jazz-derivative “Swing,” often performed by white “big” bands, was tolerated. In Germany, there was even a counter-cultural movement of “Swing Kids,” who rejected Germanic culture and Hitler Judgend alike. Once war as was on, however, not only was British/American music banned, but increasingly also music that was based on or influenced by it.

Attie and her friends, meanwhile, listened to jazz all the same. Some 65-70 years later, she can’t quite remember how they got it, though she does clearly remember that “everything was jazz, and we listened to it before the war also.” Asked to distinguish songs she heard before or during the war, she listed Singing in the Rain ( 1929 – Cliff Edwards and Annette Hanshaw), of which she would have missed the Judy Garland version by 6 months (released November, 1940), which was performed by jazz entertainers; and Cole Porter’s “Don’t Fence me in,”(1934 – though I bet the version she remembers as “jazz” is the hugely popular 1944 Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters cover).

Attie remembers “crooning” for the school band at Junior High when the net had not tightened around foreign music as much, and before the building of the Atlantikwall forced evacuation to Gouda in 1943. Despite darkening skies, curfew, and music restrictions, youth will out and the high school crowd in Gouda foxtrotted to Sunny Side of the Street (1930) and Fats Waller’s It’s a Sin to Tell a Lie (1936) at an empty factory building.

Gouda’s liberation on May 7, 1945, brought the First Canadian army, known as” the Tommies” in Holland (65 years ago this May). With them returned my grandfather, on May 9, who encouraged Attie to join the Women’s Auxiliary Corps (VHK) of the Dutch army that fought with the Canadian Army and British Army after D-Day. She was gone in two days and was in England in a manner of weeks. (See also two earlier essays about my mother and WWII, Attie’s New Neighbor 1 and 2)

There, she encountered 5 years of British and American music of the war years. She fell hard for the English Vera Lynn, the “Forces Sweetheart,” whose We’ll meet Again (1939) I so strongly identify with my mother that it brings tears of homesickness every time I hear it (so what if British and American World War II songs mean “home” to a Dutch woman living in the US?).

The themes of Attie’s Music, the music I grew up with, are those of war and purpose, longing and reunion, the wistful hope that your way of life will prevail. But also: young people getting together on a grand, even epic, scale: Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree by the Andrews sisters; Into Each Life Some Rain Must Fall, by Ella Fitzgerald and the Ink Spots (1944); Lena “Bluebird” Horne’s 1943 version of Stormy Weather (1933) and finally, the homecoming Sentimental Journey, Doris Day’s first # 1 hit (1945).

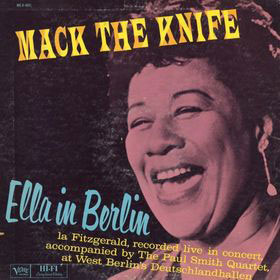

The most curious songs of the list are Lily Marlene (Lili Marleen) (1939) and Mack the Knife (1928) As to the former, how is it that a song becomes a favorite on both sides of a conflict? It crossed from Rommel’s Afrika Korps to the British Eighth Army in North Africa via the radio. Marlene Dietrich, who became an American citizen in 1939, apparently recorded it as part of a campaign to demoralize German soldiers. Another German expat, the Jewish composer Kurt Weill, had to flee Germany and died an American citizen before Mack the Knife was made immensely popular by Louis Armstrong (1956), but never more so than in a 1960 live improvised “scat” version by Ella Fitzgerald, recorded in Berlin.

And so the music crosses and crisscrosses the barriers of war, sieges and blockades, time and distance, philosophy and nationality – taking on a similar “liberating” quality in each. Did Hamburg teenagers have any sense that the “degenerate” big band swing they were dancing to was the American music industry’s white answer to the rough edge of jazz in a segregated world of racial violence? Were German soldiers aware that Marlene, now liberating the other side, was a “degenerate” herself who had loved the Berlin world of the 1920’s? As to Mack the Knife — I am neither a twentieth-century historian nor a musicologist, as should be obvious from my musings, but it can’t have been a complete coincidence that giants of African American popular music created even more gigantic hits out of the deadly serious music of socialist protest, long after the war was over, at the dawn of the Civil Rights Movement.