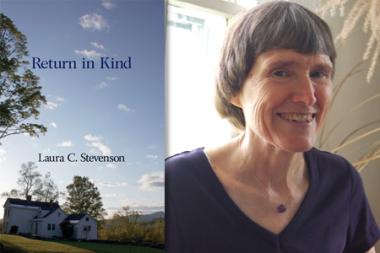

Laura Stevenson’s new novel Return in Kind tells the story of two broken middle-aged college academics—she has lost her hearing and career, he is a widower—and how, through unraveling the tragic, generations-old mystery hidden in a rural Vermont farmhouse, they find healing and each other. It is her fifth novel, her first for adult readers.

“Letty Hendrickson was dead”: the prologue begins with the cast of characters learning that a colleague has died after a long bout with cancer. Letty Hendrickson was both a trustee of Mather College (a fictitious liberal arts college set in the fictitious town of Whitby, Mass.) and the heir of the school’s founder. While her colleagues are melancholy about Letty’s passing, there is relief, too. Her relationships, it seems, were complicated, and she was more respected than liked. The story details the reverberations of her layered legacy.

We learn about Letty and the world she left mostly through her grieving husband, Joel, a renowned Spenser and Milton scholar who has not published since his wife first fell ill half a decade ago. Theirs was a difficult marriage, but he is still stunned to find that her last will and testament apparently snubs him by bequeathing many of their priceless heirlooms (which she inherited from her benefactor, the school’s founder) to the college. He inherits a Vermont farmhouse he never before knew she owned.

Friends point out that while the buildings on the property are probably worthless, if the property were subdivided, the sale of the lakefront real estate, right in the middle of prime ski territory, could make him a millionaire. Joel decides to visit the property for a few weeks to determine what to do with it. He finds room and board in a neighboring farmhouse, owned by Eleanor Randall Klimowski.

Eleanor had once been a professor at another college, but six years prior to Joel’s arrival, she had been fired because of her increasing inability to hear. She had retreated to her family’s summer home in southern Vermont to lead a cloistered life cleaning the homes of wealthy ski vacationers. Her deafness had left her with a “hunted, apologetic” look, and as she reflects at one point, “Disability was a buzzword that provoked social consciousness. But its attendant inability provoked only irritation, especially the inability to handle phone calls. How many jobs had she lost to scheduling mixups since March…?”

The above more or less describes the situation in which the author found herself not long before she began writing the book during a sabbatical in the early 1990s.

When I first met Laura Stevenson nearly 25 years ago, she had left a professorship at another college because of her diminished hearing and had spent two years holed up in her family’s Wilmington, Vt. farmhouse, making a living cleaning other people’s houses and wondering if she’d ever make use of her Ph.D. or teach again. Luckily, a writing instructor position at nearby Marlboro College opened up, and she returned to the world of academia just as I was entering college as a freshman student.

Marlboro College is a very small school (when I attended, there were roughly 200 students), and its academic model is based loosely on what you’d find at a European university. While there are some traditional classes, after their freshman year, Marlboro students decide on a direction for their studies and team up with a professor to act as their tutor. Together they build a curriculum to match the student’s needs.

For Stevenson, this one-on-one dynamic was something that could possibly salvage her chosen career path. She’d left the previous college position after she’d given a lecture and suddenly discovered she couldn’t hear any of the questions from her audience. Face-to-face was the only way she could comfortably interact with her students.

I arrived at college with a 700-page manuscript I’d been working on and had dreams of getting published.

When I started working with Laura, she had hearing aids, and I quickly learned that during our conversations I had to look her in the eye (so she could see my face) and make certain not to mumble. By the time I graduated, our tutorials had turned into one-sided shouting matches, and when that didn’t work, I’d taken to explaining myself using a pen and paper. By the time I had been gone a couple of years, hearing aids were useless to her and her students sat at a keyboard, typing their questions and comments.

Interviewed last week, Laura Stevenson explained to me that part of the impetus for writing Return in Kind was to take on the challenge of writing a novel from the point of view of a deaf person. The chief difficulty, she found, lay in not being able to use conversations as a means of delivering information. As in real life, discussions her other characters had with Eleanor are difficult and largely one-sided; while her dialog is rendered complete, what she hears is fragmented and interspersed with “mxmx” to simulate the garbled feedback that often interferes with her understanding. Instead, the story’s complex narrative unfolds through carefully staged scenes, journals, interior monologues and flashbacks.

The most dramatic and important conversation in the story occurs when Joel finally grabs a legal pad and begins to write his thoughts out to Eleanor. It’s a masterfully written scene and illustrates an observation Stevenson had made in the classroom about writers forced to write what normally they would say.

While Joel is a highly educated, literate man, his marriage to Letty had left him repressed and out of touch with his own emotions. Though he spends the novel solving someone else’s mystery, many of the clues are from his own troubled life. Until he begins conversing with Eleanor through the legal pad, he’s unable to express much about what his married life had been like.

But then, as Eleanor makes observations based on what he’d said to her, he begins to get defensive and deny some of what he initially said. All Eleanor needs to do is flip the pages back, and there are his words in his own hand.

In the classroom, Stevenson pointed out in the interview, she found that students who wrote run-on sentences or used sloppy grammar in the work they submitted had no such difficulties when forced to make their point as quickly as their handwriting or typing would allow.

*

Like Eleanor’s deafness, the book’s setting in the hills of southern Vermont during the early 1990s is another autobiographical touch that allows Stevenson to explore how that world has evolved in the last 50 years, as well as the meaning of value when it comes to our heritage.

Early in the book, Eleanor reflects on “the world of her childhood. The post-war world that created academia’s Golden Age at the same time it destroyed hill farming in Vermont. College professors from Massachusetts to Ohio who, like her father, could suddenly afford abandoned farms. The world of summer gentry. How certain, how natural, how wide-ranging it had seemed. And yet how cloistered, how limited it had been.”

Like Eleanor’s family, Stevenson’s father was a professor who bought the house Stevenson now lives in for a price that seems microscopic in today’s bloated market. Also similarly, Stevenson and her heroine have spent their adult lives struggling to hold on to their slice of the Golden Age, as many properties around them were sold off and divided into lots for vacation homes.

Part of Joel’s struggle when he arrives at the home Letty bequeathed to him is determining whether to salvage the building or simply put the property into a realtor’s hands and await the check. As a scholar of Milton and Spenser, Joel places great value on antiquity, and yet, as someone evaluating his choices at a crossroads in his life, he finds himself thinking only in financial terms.

“[T]he inflated ‘value’ of past beauty defiled the very act of loving [an object],” Stevenson writes. “Even he, the romantic, couldn’t look at Eleanor’s Chippendale desk without thinking that selling it would enable her to give up cleaning houses and renting rooms for years. Twenty years ago, the thought would never have crossed his mind.”

*

Reconnecting with Stevenson’s work after years of pursuing my own, I’d anticipated that I might get hung up watching her technique rather than paying attention to her story.

But the great strength of Return in Kind is that Stevenson has constructed an intricate web of a story in which the challenges of a scholar’s deafness and a contemplation of the nature of value are central to a highly compelling narrative.

Though the book is full of worldly scholars weighing deep issues, instead of a dissertation, the book reads like a thriller that blossoms into an unexpected romance. It is full of wit and wisdom, but it also is loaded with drama.

Even though, at first, it was something of a trick for me to divorce reality from Stevenson’s fiction, I quickly became absorbed and stopped wondering whom each character represented in the real world. Eleanor and Joel came alive with their own voices and traits, and I quickly became invested in them and their story.

And, as with the best mysteries, the book’s conclusion invited me to go back and rethink what I’d read and re-evaluate characters and scenes in the light of the final, tragic revelations.

Sure enough, the economy of words she had taught me to strive for was evident here. Characters and scenes fell into place: there were no superfluous sequences or unnecessary diversions. What had been an enjoyable, exciting read the first time through has become something deeper, more poignant and ripe for considered reflection.

There will be a book launch for Return in Kind at the Brattleboro Art Museum at 7 p.m. Friday, July 23.