The other day, an eight-year-old visitor was mesmerized by a map of Greater Boston that hangs in my kitchen. The map is nothing fancy. It’s the kind that might have hung in a real estate office before the advent of GPS devices. After my visitor determined that his house would be somewhere outside the map, he remarked how wonderful if it would be if he could just pick up any location and move it wherever he liked. That’s when I realized that in his world, maps are not supposed to be made of paper; instead, they are interactive systems that appear on screens.

I relate this anecdote because it brings up some of the quandaries involved in working with historical documents in the digital age. From my visitor’s perspective, maps and other digital documents give their viewers a certain degree of power. If my wall map were a digital object, my visitor could transport Cambridge to Revere, or decide that Logan Airport really belonged in Wellesley. Those of us who configure historical documents for web presentation face a somewhat similar set of choices. We don’t have the latitude to alter obvious historical realities. If, for instance, I added my signature to the Declaration of Independence, it would hardly amount to a hoax. But now that we can transform all kinds of digital objects with a few clicks, we are obliged to ask ourselves how the changes we make in the interest of aesthetic appeal or visual consistency affect historical accuracy.

This slippery issue has come up repeatedly in the digital humanities project that I’ve been working on lately, “Mapping Thoreau Country: Tracking Henry David Thoreau’s Travels across the United States.” Thanks to generous support from Mass Humanities and UMass Lowell, the Thoreau Society is collaborating with other educational and cultural organizations to develop a series of permanent digital exhibits that will use facsimiles of historical maps to document Thoreau’s travels, starting with his excursions in Massachusetts, then moving on to his journeys to Maine, New York, New Hampshire, and Minnesota. Drawing from collections at public libraries, historical societies, and other institutions, as well as digital objects in the public domain, we aim to illuminate Thoreau’s role in American history by constructing a map-based platform that will organize his observations on the many places he visited, situate his writings within their historical context, and chronicle his encounters with some of the most significant literary and political figures of his age.

Although our research is far from complete, we’ve already collected a wide array of documents that will help to dispel some of the myths about Thoreau that have arisen over decades. For example, contrary to the lingering notion that he almost never left Concord, our Massachusetts map is now populated with documents that show not only that he delivered lectures in well over a dozen cities and towns, but also that he almost always accepted the many invitations he received to lecture again in later seasons. Similarly, belying the popular view of him as overly serious or, by some accounts, downright sour, our page on Danvers includes a letter from Emerson describing how he had arranged for his friend to lecture there by informing the Lyceum Secretary that Thoreau’s most recent talk in Concord had so amused the audience that “they laughed until they cried.”

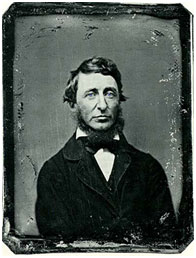

We certainly intend to add to these examples and, we hope, provide an accurate rendition of Thoreau’s doings throughout the state. But in configuring these materials for digital display, I often wonder if the changes that I’m making might stray into distortion. If for example, I take a letter from Hawthorne to Thoreau that I found on Google Books, should I emphasize it as an historical document by aging it in Photoshop? Or in formatting the daguerreotype that Thoreau had made of himself in Worcester in 1856, would it be legitimate to tint his eyes blue, making him look a bit more as he reportedly did in real life? The daguerreotype is, after all, merely a “likeness,” and one which, according to Thoreau, “my friends think is pretty good – though better looking than I.” Since these comments seem to suggest that the portrait was not exact, I also wondered if I might make Thoreau a bit more attractive if I gave him a haircut and straightened his tie. But then I read multiple descriptions of his habitually careless approach his appearance, including James Kendall Hosmer’s recollection that Thoreau’s “hair looked as if it had been dressed with a pine-cone.”

We certainly intend to add to these examples and, we hope, provide an accurate rendition of Thoreau’s doings throughout the state. But in configuring these materials for digital display, I often wonder if the changes that I’m making might stray into distortion. If for example, I take a letter from Hawthorne to Thoreau that I found on Google Books, should I emphasize it as an historical document by aging it in Photoshop? Or in formatting the daguerreotype that Thoreau had made of himself in Worcester in 1856, would it be legitimate to tint his eyes blue, making him look a bit more as he reportedly did in real life? The daguerreotype is, after all, merely a “likeness,” and one which, according to Thoreau, “my friends think is pretty good – though better looking than I.” Since these comments seem to suggest that the portrait was not exact, I also wondered if I might make Thoreau a bit more attractive if I gave him a haircut and straightened his tie. But then I read multiple descriptions of his habitually careless approach his appearance, including James Kendall Hosmer’s recollection that Thoreau’s “hair looked as if it had been dressed with a pine-cone.”

So my best guess when it comes to maximizing the accuracy of digital historical documents is to do as journalists would do if we lived in a better world, which is to rely on information gathered from more than one source. Even though I might wish, along with my visitor, that I could move Logan to Wellesley, our new-found power to remake images and other materials doesn’t permit us to take any new liberties with historical evidence.