“Before I had a trauma problem. I could not study. I was always suffering from headaches. I was always crying. I was hopeless about life because I thought was alone on earth.” That’s the first thing Fifi said to me when we began our interview with her. It wasn’t our first conversation.

Fifi is a law student. She’s fluent in two languages. She’s 26 years old. She lives in an 8 x 10 room with no bathroom, no kitchen. The space is sparsely decorated with photos of friends and her parents taped all over the walls. Fifi’s parents and sister were killed when she was 10 years old. Last year, Fifi finally found out exactly what happened to her dad. Fifi is traumatized and she knows it. I knew it the moment I met her. It’s apparent in her eyes, in her actions, in the way she speaks. She lives alone and in fear, in fear of perpetrators, in fear of her extended family– her only relatives who are still alive. I also knew it because I knew she survived the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. Now, to be clear, this is not to suggest that all genocide survivors are traumatized or continue to suffer from post-traumatic stress. Fifi does.

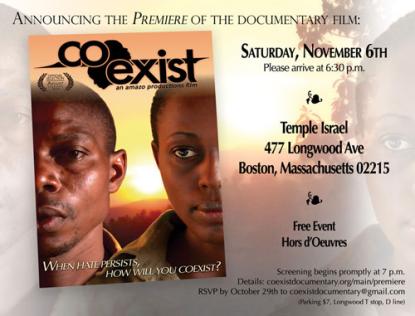

In the callous world of documentary filmmaking Fifi’s suffering makes for a compelling story. So as a filmmaker meeting Fifi for the first time, I wanted to figure out how to make her comfortable sharing her story, on camera. Perhaps more importantly, I had to consider, what possible benefit could she derive from sharing that story? While in Rwanda in the summer of 2009 for production of the documentary film, Coexist , this was a question asked and answered every day.

I knew this could be the most important question facing me as a filmmaker before ever entering Rwanda. I had been there once before, in 2006, when the memories were even more palpable. Rwandan mental health experts have found that 28% of Rwandans suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder. Yes, more than 16 years since the genocide ended more than one quarter of the country suffers from PTSD. For comparison the rate is 3% for Americans, and 19% for Vietnam veterans.

In 1995 UNICEF found that almost every single Rwandan witnessed an act of violence and nearly 80% of them witnessed murder. So the question was not whether people we met suffered trauma, but how to deal with the fact that they surely did. Painful as those statistics are, I understand it’s essential to somehow find a way to get personal. I knew from my conversations with those better trained in psychology than me, that the very thing we needed people to do – tell their stories– could be retraumatizing. I learned that creating connection, building a relationship, and creating a safe space are essential ingredients to make sure no one is retraumatized.

In our first conversation Fifi and I could connect some in French. Through that direct dialogue, I found out that Fifi was just as interested in getting to know me, as I was in learning about her. “Where do you live… are you married?” (This is the first or second question from most Rwandans.) When the answer is “no” it is presumed you are still in school. So the question follows, “Where do go to school?” People who have experienced trauma are still people. Fifi still wanted to talk about the mundane, the everyday. In my experience the people I’ve met actually crave that even more than someone with a more “normal” life experience.

In my experience we were talking with people who were unfamiliar with most of our equipment and our language. Baring one’s soul is daunting in any setting, in any language. Now imagine doing this with a director, cinematographer, audio guy, translator, lights and camera all aimed at you. This is why the best advice I received before heading to Rwanda was, “Your translator is the most important person on your team.” Our primary translator was incredible. Her ability to relate and emote was vital to our success.

I suspect others might be disappointed with their results because upon meeting a potential subject because they immediately turn on the camera and (worse) the lights, and attempt to dive into a conversation about the most painful experience their new acquaintance ever had. Imagine meeting your average American in a social setting, asking their name and then saying, “So, tell me how you felt when your mother died?”

The uncomfortable alien presence of crew and equipment makes creating that safe space all the more important. The five of us crammed into Fifi’s room, a couple of us on the bed and the others on furniture. It was the only place she felt safe doing the interview.

While the most compelling material comes when you get personal and create a connection, there is a limit. When your subject is crying, it can be counterproductive for you to cry. This might be controversial, but I think it’s true. If your goal is to capture a story, then losing your composure can impinge upon that. You can be compassionate, you can be caring, you do not have to detach. But, if you start crying you take your subject out of that moment and into your moment. This happened with Fifi, there was a particularly painful moment where I realized that everyone was crying, including me. Fortunately, my colleague helped get me back on track. I steered back into safer territory and focused on the mundane, the things Fifi would be comfortable speaking about. This allowed us to continue, and eventually delve much deeper and learn things about Fifi we never knew. Without that composure we may have never heard Fifi’s entire story. The last thing she said turns out to be, according to many viewers, the most poignant moment in our documentary.

So what does Fifi get out of this? I do believe in the axiom I’ve often heard, that the telling of a story can be therapeutic in itself. I’ll add this qualifier– after creating a safe and comforting environment. It is also my hope that viewers who see Fifi’s story will be compelled to help and I will do my part to offer practical ways to do that. Maybe you’ll think of some ideas when the film premieres this Saturday, November 6th at 6:30 p.m. in Boston. Because this isn’t just an ideal, this is a practice we (my team and I) firmly believe in. Films don’t change the world. You do.™