Paul Krassner had a front row seat to the 1960s, and he was arguably the era’s loudest and most influential heckler.

He reported on events from outside the mainstream, preferring to work with fringe and underground sources to tell stories no one else would touch. A first person account of a working con man might run next to an eye witness account of the violent racial tensions in the South. When Jackie Kennedy insisted two chapters of a new biography of her husband not be published, he got his hands on them and did just that. His radical social and political views were found on national newsstands all through the conception, birth, life and death of the civil rights, peace and drug movements. Norman Mailer, Alan Ginsberg, Lenny Bruce, Ken Kesey and Abbie Hoffman were all profiled in the magazine and were also occasional contributors. Timothy Leary was lionized, and politicians from Kennedy to Nixon were skewered with lobotomizing precision. His motto became, “Irreverence is our only sacred cow.”

Despite stating in the headline of the first issue of his monthly news and satire magazine that he was “young and angry,” nothing in Paul Krassner’s maiden editorial conveyed either adjective. Instead, he explained the problems his audience faced and that his publication hoped to answer. He stated his intent and laid down the ground rules:

“…[T]his editorial will be written in first person singular, as a sort of symbolic gesture toward a society where conformity has replaced the weather as that which everybody talks about, but which nobody does anything about,” Krassner wrote. It’s easy to forget he’s writing half a century ago.

Describing the deadlocked world he wrote for, he quoted psychiatrist Edward Edinger, a contributor to that month’s issue, defending his own work on “The Role of Myth”: “I did not intend [my series of presentations] as anything angry or partisan. To my mind there is already far too much angry partisanship at work. This usually amounts to one group’s projecting its own inferior, shadow qualities on to the other, and then berating it for having those qualities. This behavior is particularly evident in the controversies of politics.”

A quote from television critic Jo Coppola provided further detail of the media landscape Krassner faced and a clue at his proposed remedy: “Good comedy is social criticism—although you might find that hard to believe if all you ever saw were some of the so-called clowns of videoland…. Comedy is dying today because criticism is on its deathbed … because telecasters, frightened by the threats and pressure of sponsors, blacklists and viewers, helped introduce conformity to this age.”

Krassner’s purpose, he writes, “is to provide satirical commentary on the tragicomic currents of our time.” He had two axes to grind. “One ax is reality, as opposed to ‘the land where dreams come true.’ The other ax is individual freedom.”

Krassner launched his new publication in 1958, charging $3 for 10 issues. The first issue was assembled in the offices of the fledgling Mad Magazine in New York City, which was edited by his friend Harvey Kurtzman. Krassner’s small, black and white, text-heavy, advertising-free publication was packed with news, information and voices rarely heard candidly in print or anywhere else. After a hiatus in the ’70s, it returned in the ’80s, and finally bid farewell in 2001.

Completed this month, an archive of all 146 issues of The Realist is now available online (www.ep.tc/realist) for free, providing endless hours of shock and delightful awe.

After an exhaustive hunt to locate copies of each issue, each page of 2,900 pages of fragile newsprint has been digitized. Sometimes, the archivists report on the site, the very act of placing the flaking pages on the scanner destroyed them. The images of the pages have been posted, preserving the look and feel of the paper. While the stories and illustrations are top-notch, so is the entire layout of the publication, and it’s a pleasure to explore in its original format. Long stories meander through the pages. Smaller features are sprinkled throughout the mix, and there are dozens of one-offs and clippings from the far corners of the national print media. Clicking on a page advances archive visitors to the next one, and it’s easy (and a lot of fun) to get lost in this cultural and historic prism.

The wealth of information and perspective the archive offers online is only matched by the amazingly wide lens through which Krassner saw his Internet-free world. He must have had a close relationship with his mail man and an office choked with letters and dog-eared publications. Nothing in his prose suggests he writes without the Manhattan skyline in view, and yet his paper includes clippings, reporting and analysis from nooks and crannies across the country.

Not everything in The Realist corresponds to the current day world view. Krassner’s incendiary attacks against Catholic religion seem less heated now that even the Pope’s been making apologies, and, though still shocking, his reports on the dire racial conflict brewing throughout the nation at the end of the ’50s sometimes seem exhausting considering he’s long since proven his point.

The jury was still out for many readers of the early Realist regarding their attitudes toward homosexuality and whether it was a choice or a condition, let alone whether it was acceptable. While Krassner happily included discussion and graphic representation of all kinds of acts commonly thought lewd and indecent, his crassness had a strong hetero bent. He often published letters from readers who thought he was either too supportive or too dismissive of gay culture and politics.

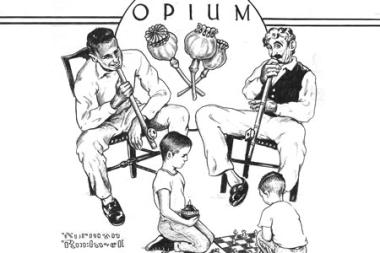

There was little confusion on where Krassner stood on the merit of getting baked or dropping acid. Even for a student of the ’60s, it’s surprising to see the earnestness with which that era took their unprescribed medication. In the pages of The Realist, the visions hallucinogens offered were as significant as any argument for civil rights.

Krassner tuned in and turned on with the rest of them, and included in the archive is an essay he wrote about different luminaries he tripped with, entitled, “My Acid Trip with Groucho Marx.” He writes, “By the mid ’60s I had become such a dope fiend that I kept my entire stash in a bank-vault deposit box. Once a week I would don my Cosa Nostra sweatshirt (“We aim to please!”) and get my supply of LSD—to give away, sell, swallow, whatever. It was, for you brand-name fans, Owsley White Lightning—300 micrograms of separate reality. I bought my acid from Dick Alpert to finance his trip to India where his guru renamed him Baba Ram Dass.”

It’s this stash he has the opportunity to share with Marx. The elder comedian was going to be in a new movie that featured use of the drug, and he was curious. Krassner and he met and “ingested those little white tabs one afternoon at the home of an actress in Beverly Hills.” Krassner liked listening to rock and roll albums while tripping, but all that was available were Bach albums and Broadway musicals.

Toward the end of a happy afternoon, Marx said, “I’m really getting quite a kick out of this notion of playing God like a dirty old man…. You wanna know why? Do you realize that irreverence and reverence are the same thing?”

“Always?”

“If they’re not, then it’s a misuse of your power to make people laugh.”

“And right after he said that,” Krassner wrote, ” his eyes began to tear.”