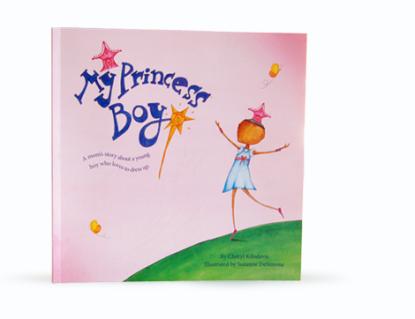

Over the past few days, I’ve read—and reread—Cheryl Kilodavis’ lovely and loving picture book My Princess Boy the way a mama to a nearly three year-old does (that’s to say—and reread and reread). The message of the book is direct and simple: a boy who loves pretty things should be granted the freedom to be just that, a boy who loves pretty things.

As is the case in real life though, the plot thickens. While parents and friends and teachers and strangers should honor him for who he is—in essence: twirl, baby, twirl—that’s not always the whole story. Just because he should get to twirl through life without worry, some people give him a hard time about his penchant for pink and for princesses. Kilodavis reminds us—and anyone who knows a Princess Boy—that people who have a hard time with twirling boys bedecked in twirling clothes exist. Rather than agree with their boys-must-be-rough-and-tumble-or-bust notions, we can encourage our boys to twirl if they like (and our girls, too).

My copy of the book arrived last week (and I will give it away! Read on to find out how to win). At the same time, I took temporary possession of Peggy Orenstein’s Cinderella Ate My Daughter, a book I devoured over the past couple of days (as did my twelve year-old son). Orenstein makes the case that a book like My Princess Boy be essential preschool reading (and it is), because in 2009, sales of Disney Princess merchandise reached the four billion dollar mark. And those sales were aimed exclusively at a female demographic. That’s a whopping amount of girly. It’d be hard for a Princess Boy to squeeze in (unless he had big sisters, some mothers would argue).

One of the more interesting and disturbing developments of this Disney-ifcation and commercial commoditizing of play—to every princess gown I’m guessing a light saber is sold—is that imaginative play the way we’ve known it—stick as gun, sword, and cane—begins to resemble ice floes in becoming very thin and at risk of melting away entirely. One researcher Orenstein met noted in this highly commercialized era, play has become homogenized; it’s no longer emanating from children’s imaginations but from storylines fed to children through so many media platforms they become essentially unavoidable. Media and merchandise have hijacked make-believe (Ground control to Major Tom).

Lest we think it was ever only Free to Be in the grooviest and most open-minded sense, Orenstein shares her daughter’s response to William (who famously wants a doll), which is to be surprised that his wanting a doll is a big deal (Daisy lives in Berkeley, California) and of Dudley Pippen Daisy asks her mama, “What’s a sissy?” Supporting boys in breaking stereotypic molds isn’t new—and of course, stereotypes aren’t new, either.

For a mother like Kilodavis, the question of what boys should wear or how they should act was answered a long time ago. Her boy loves pink and loves twirling and she loves her boy.

I applaud anyone who can urge us to see the most tender and uplifting message in all this cultural confusion—and in our own confusion.

**

If you are interested in having your name go into our now-infamous bowler hat for a random drawing by a dapper young eight year-old and his by then three year-old side-kick to potentially win a copy of My Princess Boy, leave a comment with your pink-inspired thought.

**

Oh, and until the voting period for the Valley Advocate Readers’ Poll ends February 9th at noon, I’ll ask for your vote (Standing in the Shadows Best Local Blog under Media Mavens). Thank you!