In his January 10 post, Patrick Vitalone asked: why do we save historic resources? and which? Citing two cases involving modernist architecture, with whose outcome he disagreed, he furthermore asked whether preservation is “to be an unwavering commitment to any and all history, even if the ugliness of the past prevents the beautiful construction of something new?”

Honestly, I know of no properly trained preservationist who thinks that we can (or should even try) “to preserve everything and anything,” much less, condemn our communities to aesthetic oblivion for the sake of abstract ideals. I suppose I can understand the frustration, though. Here in Amherst, a grassroots coalition called Preserve UMass (PUMA) temporarily halted construction of a new campus recreation center, which threatened the century-old Stucco Cow Barn that embodied the University’s pioneering role in scientific agriculture. Our Historical Commission (which I chair) has come in for criticism for imposing demolition delays on an industrial barn and a historic fence, and for attempting to provide protection for resources through creation of a local historic district. The public is commendably devoted to history and historic sites but not necessarily well informed about preservation principles and practices.

We need to start by reminding ourselves that historic preservation is a relatively new concept. It came into its own in the nineteenth century, stimulated by a mixture of new historical consciousness, crystallizing national identities, and the increasing pace of social change. Earlier generations and cultures took a much more cavalier or pragmatic attitude toward the remains of the recent past.

The Renaissance art historian Giorgio Vasari employed “Gothic” as a term of opprobrium when he denounced the architecture of the Middle Ages as “monstrous and barbarous.” By the Romantic era, however, the Gothic was in vogue again, and it even reappeared in the form of architectural revival styles, from the British houses of Parliament to many an American college campus. Vasari would be horrified. When I do research in southern Germany, I always visit Ludwigsburg, often described as Germany’s largest Baroque palace. That it is, but little of the historic interior retains its original character. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Duke (later: King) Friedrich remodeled the rooms and grounds in the newly fashionable Empire style. He no more scrupled to remove the Baroque and Rococo elements than we would to replace that 1950s linoleum and 1970s shag carpeting with bamboo flooring, and those atrocious appliances in “avocado” and “harvest gold” with brushed stainless steel ones. Most Americans would be astounded and shocked to learn that Independence Hall (then: the “Old State House”) only narrowly escaped demolition in 1816.

Tastes change—as do notions of significance.

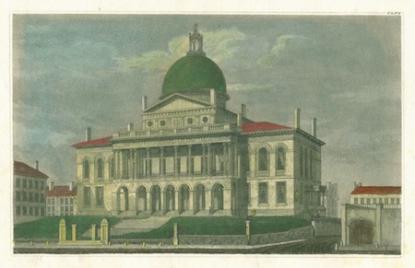

The first US preservation efforts were the work of private organizations rather than the government, and focused on landmarks associated with the history of the colonies and new nation. The Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association (1853), which saved the home of our first president from becoming a hotel with racetrack and saloon, is the classic example. Aesthetic criteria became truly important only late in the nineteenth century, as older structures and landscapes faced new threats arising from deterioration or redevelopment. Here in Massachusetts, the campaigns to save Boston’s Common and the great 1798 Bulfinch State House marked the turning point.

Beloved: the Charles Bulfinch New State House, Boston (1798); steel engraving from a German topographical work, 1830s

The private movement that focused first on sites of patriotic importance and then on the edifices of the elites has in the meantime become a broad-based coalition of private and public actors whose scope is far wider. Preservation today involves cultural landscapes, vernacular and utilitarian or industrial structures, and entire neighborhoods or districts. It includes gas stations and fast food restaurants. It embraces the sites of dark moments in our nation’s history, from slave cabins to the internment camps for Japanese-Americans. Local historical and landmark commissions assess and prioritize properties according to standards of historical and architectural significance adapted from those of the Department of the Interior.

Unloved and “unlovely”: Boston City Hall (1969)

Modernist architecture—the subject of Patrick’s complaint—poses special dilemmas. Indeed, its “ugliness” as a challenge for preservationists is a topic that I myself have pondered.

Paradoxically, I would argue, Modernist architecture suffers the unenviable fate of being both unfamiliar and too familiar. It often employs a challenging if not altogether inaccessible aesthetic, which becomes all the more alienating when combined with other disadvantages. Many of these structures are not what we would call user-friendly. Especially when constructed as part of sweeping renewal efforts, they may show little sensitivity to context. Some seem to elevate sophistication of architectural program over utility. Some are uncomfortable, not least because they were poorly constructed and disastrously inefficient in energy consumption. (Typically inadequate or uninformed maintenance merely exacerbates these problems.) At the same time, because these structures are ubiquitous and numerous, they are not perceived as either distinguished or threatened. Buildings of great power and distinction mingle with absolute mediocrities. It’s not surprising: the stock of structures from more distant eras, by contrast, has already undergone a sort of natural selection.

In the United States, resources are classified as “historic” when they reach the half-century mark. That so-called “fifty-year rule” has recently been questioned, in part because it is quasi-arbitrary, in part because most structures face drastic change or demolition in about half that time. The National Trust for Historic Preservation warns, “The significant buildings, landscapes, and sites of the Modern movement and the important architectural, social, and cultural resources of the past 50 years are among the most underappreciated and vulnerable aspects of our nation’s heritage.” Even under the current system, the buildings of 1960s modernism are now becoming officially historic. We had better be prepared for more controversy—and hard choices.

No responsible preservationists urge that we freeze all buildings or communities in time. Each case must be judged on its own merits. In recent years, the preservation movement has come to champion judicious modernization or adaptive reuse of many historic structures as the best way of reconciling historic values with the need for sustainable development and smart growth (1, 2). As the new mantra goes, “the greenest building is. . . one that is already built.” (Demolition produces almost two thirds of the material in most landfills and in addition wastes the embodied energy that went into a building’s construction: in the case of Boston’s much-maligned City Hall, the equivalent of 75,000 tons of carbon.)

To my mind, historic preservation is like environmentalism: it does not deny the need for change; it merely demands that it be responsible and sustainable. Nowadays, we recoil at the thought that our forebears caused living species to become extinct. So, too, we should pause before deciding that a given architectural style has no merit and claim to survival. And the parallel is closer than one might think: a recent study showed that zoos, though protecting some endangered species through captive breeding, tend to favor those that humans regard as aesthetically pleasing rather than “ugly.”

Are we truly so wise as to know the best interests of posterity? After all, our lives and culture would be greatly impoverished if all the Gothic buildings had disappeared, and likewise, if Independence Hall had made way for that early subdivision. Historic preservation anchors us in time and space by reminding us that we are part of a continuum. It dictates that we act humbly and live lightly in the built as well as natural environment.