In 1933, a few of the inmates at the new prison in Norfolk, MA decided to form a debate club. Their first coach was a woman named Cerise Jack, a regular visitor to the prison. For the first few years the men held practice matches amongst themselves, arguing the affirmative and negative positions of the biggest social questions of the day. They called themselves the Norfolk Debating Society, and they soon began inviting college teams to engage in formal debates. This got their competitive spirits flowing, and they became more selective, more focused. They started holding tryouts. They reserved a room in one of the administrative buildings for weekly practices. They spent odd hours in the prison library, meticulously building up evidence for their upcoming matches by combing through national newspapers, government publications, and works of science, literature, and politics.

The debates with outside college students took place every few weeks in the prison auditorium and were judged by an ever-changing three-person panel of professors, judges, lawyers, bankers, priests, and other respected citizens. Spectators from nearby towns mingled with the two hundred prisoners in the audience. Newspapers and radio stations provided local and national coverage. In their first two decades, Norfolk’s men amassed an outstanding record which included victories over top opponents like Yale, Princeton, West Point, Oxford, MIT, and Harvard. By 1966, the team’s record was 144 wins, 8 losses.

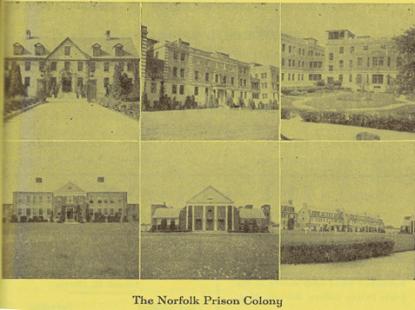

Norfolk is a critical episode in the history of criminal justice in Massachusetts–and in the swing of the pendulum between punishment and rehabilitation. The prison colony was founded in 1927 as the nation’s first “community prison.” It was the brainchild of a man named Howard Belding Gill, a reform-minded Harvard sociologist who also served as the first superintendent. He encouraged public-spirited citizens to invest their time helping to educate and interact with the prisoners. Gill believed that a prison could be most effective at rehabilitation if it maintained strong connections with the local community, and he designed Norfolk to feel as much like the outside world as possible. In many ways, Norfolk actually resembled a college campus, with a well-stocked library, a school, work training, unlocked cell doors and unbarred windows.

MCI-Norfolk is now the largest state prison in Massachusetts and one of the most visible public institutions in the area. Though most of its original architecture remains, the atmosphere of Norfolk and the approach of corrections as a whole have changed. As far as we know, the Norfolk debaters stopped competing in the ‘70s. Today, there’s very little public knowledge about the team, or about many of Norfolk’s other educational and vocational programs. There has never been a contemporary or retrospective portrait of the Norfolk debaters. At best, the team is cited as a footnote in biographies of Malcolm X, who spent two years at Norfolk and discovered a knack for public speaking there. To the best of our knowledge, the stories of the other men and women involved with the team have never been recorded.

When the two of us first learned about the Norfolk debaters we were fascinated, and surprised at how little was known about them. Some historians or activists or penology experts are familiar with the Norfolk Prison Colony, but even among people living in the town of Norfolk, very few have heard of the debates. For this project we partnered with the Norfolk Historical Commission, a small group of fantastic Norfolk citizens who also became interested in the debate team’s story and were eager to help. At our first meeting last year, they told us that the prison on the hill is not generally a popular topic of conversation around town. But one woman, now in her eighties, can remember hearing the broadcast of a Norfolk debate on the radio at her family’s breakfast table when she was a little girl.

When we began our research, we had no guarantee we would find anyone from Norfolk or from the opposing college teams still alive. We’ve gotten very lucky. Every person we find is a gift. Since receiving the “Liberty and Justice for All” grant from Mass Humanities, we’ve interviewed over thirty people, including former members of the prison debate team, their college opponents, coaches, teachers, next-of-kin, and others. We are assembling an oral history of the team and of life at Norfolk Prison Colony, to be transcribed and archived in several Massachusetts libraries. We plan to edit the interviews into a radio documentary, and we’ve recently begun work on a book. Other projects are developing as we explore ways to ensure these stories can live on and be shared with the public.

This sounds like an oral historian’s stock cliché, but all the interview subjects have incredible stories. One of the college debaters ended up working as an advisor in the White House; another is a justice on the Supreme Court of Canada. And some of the most “successful people” we’ve interviewed are the men who were once in Norfolk and became professional and community leaders when they got out. For many, this is the first time they’ve spoken about the debates (or about prison) in forty, fifty, or even sixty years. And some of the most incredible stories have come from the people who regularly crossed the threshold in and out of the prison: the educators and coaches who had their own homes and families but came each day to work with the inmates.

The first threshold that comes to mind when people think of a prison is, of course, the main gate: entrance and exit and barrier. But for the purposes of this story the real threshold space was the auditorium, where the college team and the prison team stood on the same stage. Here, for an evening, their two worlds merged. The inmate debaters wore shirts and trousers just like their college opponents. Both teams had to obey the same laws and procedures. Both were judged on the same standards of presentation and persuasion. They created a shared, third space for intellectual encounter—one in which they grappled with the most difficult questions facing their country.

In assembling this oral history, we ask a lot of simple questions. What was it like to enter the prison for the first time? What kind of debater were you? How did it feel to win or lose? How often do you think of debates now? We ask these questions of Norfolk debaters who were serving 15-year sentences, and of college opponents who came to the prison for just one evening. Of course, the answers we receive are very different, and they tell a much more complex and captivating story than a simple record of wins and losses. We’ve been trying to use these interviews to create another kind of third space, a narrative threshold, where the disparate stories from the debates can be assembled and presented on the same stage. We feel especially lucky to be doing this now—after so many decades when these questions weren’t asked, and at a time when the answers are in danger of disappearing. We hope you’ll join us in the town of Norfolk this May to celebrate the history of the team.