I was excited when I got off the train at the Park Street T stop in Boston. I was meeting Margaret for the first time. She had promised me a thrill in the park and I was more than a little curious. I had told her to look for a little bald man. She told me to look for a Boston Parks and Recreation vehicle. I spotted her first; there were lots of little bald men to choose from but only one Parks and Recreation SUV. Get in, she said, we’re going for the ride of your life.

I was excited when I got off the train at the Park Street T stop in Boston. I was meeting Margaret for the first time. She had promised me a thrill in the park and I was more than a little curious. I had told her to look for a little bald man. She told me to look for a Boston Parks and Recreation vehicle. I spotted her first; there were lots of little bald men to choose from but only one Parks and Recreation SUV. Get in, she said, we’re going for the ride of your life.

Driving in Boston is thrilling enough but we weren’t heading into Boston traffic. In fact, there was no automobile traffic at all because we were driving through the Boston Common on the pedestrian pathways. Margaret Dyson, an employee of Boston Parks and Recreation, does this all the time but for me it was new and fun. Everyone else had to trudge through the Commons and the Garden and the Riverway and the Arboretum and Franklin Park, but I got to ride and look and talk. I was getting a personal tour of Frederick Law Olmsted’s Boston, a city the famous landscape architect changed dramatically and for the better.

If Olmsted is all but a household name today, that repute comes almost entirely from his design or co-design of large urban parks. He was co-designer with Calvert Vaux of Central Park, the first great American urban park; head of the first Yosemite commission; leader of the campaign to protect Niagara Falls; designer of the U.S. Capitol Grounds; site planner for the Great White City of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. He did major park designs in Brooklyn, Detroit, Montreal, Rochester, Buffalo, Louisville, and Chicago. But Olmsted also created site design for private residences, campuses, railway stations, hospitals, planned suburban communities, armories, and mental institutions. Adam Gopnik, writing in the New Yorker, understandably arrives at the pungent question: “Was there a patch of grass in nineteenth-century America  that he didn’t design?”

that he didn’t design?”

He worked as a surveyor, seaman, farmer, journalist, author, and editor; he ran the precursor to the Red Cross, the U.S. Sanitary Commission during the Civil War, and then managed one of the world’s largest mining operations near the end of California’s Gold Rush. He’s familiar to us for his parks, but before he ever designed a landscape, he was an influential social reformer, a writer with a startling influence on the fiery debate about slavery. Later he was among the first advocates for the preservation of natural areas (Yosemite and Niagara Falls) in America.

And besides all of that he reshaped Boston. Margaret zipped along the pathways of the Fens, popped onto city streets by the Museum of Fine Arts, and then took me over to the Muddy River. Olmsted came to Boston, she told me, in the late 1870s when the city held a competition for a park in the Back Bay area. The first prize winner was a local florist. A rank amateur. The florist did not want to carry out his design, and nobody else did either. Boston called on Olmsted. As Keith Morgan, an historian of architecture at Boston University said to me, “The site of the Back Bay Park was in terrible shape. In fact, Olmsted always called the place an ‘improvement,’ never a “park.” It was a hundred low-lying acres of reclaimed land that were bathed with the sewage pouring out of the Muddy River, and flooded at high tide. Basically a large, muddy, stinking flat. How do you make a park out of that?”

Olmsted made a park by diverting the sewage into underground conduits, then built an entirely artificial salt-grass marsh; an invented stream wound among the tall grass. He’d saved the Back Bay neighborhood from a smelly, unclean eyesore, and a health hazard to boot. It’s not wild at all but it looks completely natural. What Olmsted did was transform an urban landscape polluted by waste into a habitat that works the way it’s supposed to. Olmsted, Margaret points out, was a bit of a magician, tricking the viewers into seeing what he wanted them to see, not the complex engineering that made the illusion work so well.

Olmsted had more tricks up his sleeve. In the late 1860s he helped re-design the park system in Buffalo, calling for several parks to be linked by parkways to each other and to the center of the city. It was the first integrated park system in the country, an idea that Olmsted refined when Boston came calling again. He took the already popular Boston Commons and Boston Garden and connected them into a series of parks that form a “greenway” streaming seven miles out from the center of the city – The Emerald Necklace. The largest jewel in the necklace is the 500-acre Franklin Park.

Margaret pulled the car up to the zoo gates at Franklin Park and we got out and turned our backs to the menagerie and faced the giant open fields. As Charles Beveridge, one of the great Olmsted scholars and an editor of the Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, told me in an interview, “There were no ponds in the original plan. If there were few buildings in Central Park in New York City, here he called for even fewer – and the biggest one, the Playstead Overlook Shelter, was tucked away, almost unnoticeable. Simple, quiet, calm. None of the self-conscious elegance of Calvert Vaux’s Central Park arches and bridges. There’s a masterful artlessness to his Franklin Park design.”

Olmsted had come to Boston after a series of political and artistic setbacks in New York. Margaret, surveying all the intrusions on Olmsted’s original park design, told me that here, in Boston, things would finally work out, that his work would be valued. “But he would be disappointed in the way we in Boston have treated Franklin Park,” Margaret said. “Vandals destroyed all the small structures in the park a long time ago. The Overlook shelter burned down, and was never replaced. The area he called The Greeting was never built. A nursery is now the maintenance yard for the Parks Department. A meadow in his Country Park has a hospital sitting on it. The Playstead is the site for a large stadium. And so it goes.”

Olmsted’s problem was not design, it was his clients, or better said, it was the way he clashed with his clients. He knew exactly what to do with physical and biological processes but was stymied by the social and political ones. It was not unusual for Olmsted to be thrown off a job. Stanford University gave him the heave ho, as did the city of Spokane. When he did finish a commission, and he did thousands, he was often unhappy with what happened later on.

Perhaps he was too headstrong to be politically adept, but Olmsted was acutely aware of the fallout from politics. He once described the damages to an architect-friend:

Suppose that you had been commissioned to build a really grand opera house; that after the construction work had been nearly completed you should be instructed that the building was to be used on Sundays as a Baptist Tabernacle, and that a suitable place must be found for a huge organ, a pulpit, and a dipping pool. Then… you should be advised that it must be so refitted that parts of it could be used for a court room, a jail, a concert hall, hotel, skating rink, for surgical cliniques, for a circus, dog show, ball room, [and] railway station. This is what is nearly always going on with public parks…. It is a matter of chronic anger with me.

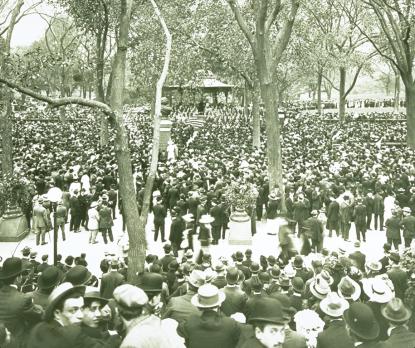

I got the impression that Margaret shared a bit of Olmsted’s anger; that she would prefer to see Olmsted’s vision of the Franklin Park without the imposition of ball fields and golf courses and stadiums. We drove outside the park and she pointed out the triple deckers in the crowded neighborhoods nearby. “These areas were teeming with immigrants in the late 19th century and they needed places to play ball and have fun. Perhaps they weren’t as genteel as Olmsted would have liked, but his sense of design had such appeal that the masses loved the parks. So maybe a little compromise on how those parks are used isn’t such a bad thing.”

As we returned to the Park Street T Station, this time via regular old city streets, I thought about what Olmsted had done for Boston and American cities more than one hundred thirty years ago. He had predicted the growth of the cities and knew that paving over everything would have more than just terrible environmental consequences. Without parks in the center of densely packed urban areas city living would be a soul deadening experience. He didn’t settle for simple open space, what he strived for was an aesthetic ideal, a landscape that would inspire the contemplation of beauty and the appreciation of peace. He wanted nothing less than to remedy the ills of modernity. Walk the Emerald Necklace and see how well Olmsted preserved a bit of Boston’s wild past and at the same time turned the profession of landscape architecture into a fine art. That, for me, is a thrill in the park.

This essay is adapted from a proposal for the documentary film “Frederick Law Olmsted: Designing America,” written by Ken Chowder, a co-production of WNED, Buffalo/Toronto and Florentine Films/Hott Productions, Inc.