![]()

I’m sitting in one of the better known architectural spaces in the world: the Frank Lloyd Wright drafting studio at his Taliesin estate. At many of the tables sit the students of the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture, which offers both B.A. and M. Arch. degrees.

Whatever degree these bright and energetic student acquire, when they graduate, they will be in trouble. In a country where 95% of the population already uses no architect at all for their dwellings, and during a recession in which architecture has, by all accounts been the hardest hit of all the professions, what will become of them?

The New York Times recently published a picture and a story about an architect who had set up a classic lemonade stand in downtown Seattle with a big sign: “ARCHITECTURAL ADVICE, 5 CENTS.”

The question of architectural advice – price aside – has lately become acute for me and my wife, Karen Ellzey. Five years ago, we rashly purchased one hundred and twelve acres of land out here,

which was about a hundred and seven acres more than we were looking for, and promptly began planning to build a small house on it.

Why did we two hard core city dwellers do such a mad thing? I think I found a clue in a fascinating book, The Origins of Architectural Pleasure, by Grant Hildebrand, who attempts a Darwinian explanation of why we like what we like. When humans were living on the African savannah in the early days, there were two basic architectural impulses, he speculates: “refuge” and “prospect.” We wanted shelter and protection from our predators, but we also wanted a wide field of view from which we could spot enemies early on and also prey on lesser beasts.

We are no longer living in subsistence mode, but it’s likely parts of our brain still are, and refuge and prospect perfectly describes the emotional effect of the environment we found there, and is the only way I can account for the irresistible urge to acquire it which struck us both instantaneously.

So we knew now where to build our house. But what and how to build is quite another question.

There are several aspects of the house design/build process that have come to haunt me. One is the huge expense and complexity of building a residence of any kind. A house is by far the most expensive thing anyone acquires in a lifetime, which is scary in itself. But in addition, when you start from scratch with an architect, you are basically committing yourself to make an investment of several hundred thousand dollars based on lines on a piece of paper. This is radically different from buying a house that already exists.

I have only owned two houses in my lifetime, the more significant being the one Karen and I bought eighteen years ago and live in now in Boston. That house was a promising 1898 Arts and Crafts cottage whose interior – covered with with 1970’s kitsch, could not conceal its basic gracefulness. So we knew what we were buying, and what needed to be done to “make it our own,” as it were, which turned out to be a lot.

But Karen and I could sit in the house we were contemplating buying, and fully “feel” (touch, see, smell, hear) the space the house enclosed, which was critical, because I have always felt the force of the Lao-Tzu quote the adorns some Taliesin wall, according to which “the reality of the building lies not in its roof and walls, but in the space within.”

How in the world can space be shown in two dimensional drawings? There are several problems here. One is that almost all architects, and that includes Frank Lloyd Wright in his day, provide the client with a floor plan, several elevations, and a single rendering, i.e., a three dimensional simulation, of what the house will look like from at least one view – always from the outside.

But we care much less about what the house will look like from the outside – that is for passers-by. What we care passionately about is what the house will feel like from the inside, when it is simultaneously sheltering us and showing us glimpses of the lovely landscape outside. That perspective is much more difficult to draw, is necessarily more “subjective,” and is therefore almost never done.

But even assuming it could be, how could we know what it would actually feel like?

One hedge is to have a three-dimensional model made. Models are quite expensive, but not in comparison with the thing itself, and are not only useful for clients, but for architects themselves as study sources for design changes that need to be made. I was talking to Aris Georges, one of the senior architects at Taliesin, who is Greek. He told me that it was not uncommon in Greece for architects to make half a dozen or more models at various stages in the design process to help guide them. Not so in the United States, where models are comparatively rare.

Architects here seem to prefer, if pressed, to do computer generated “fly-throughs,” which I have come to dislike intensely. Yes, they simulate three dimensions, but look to my eye feel utterly unnatural. They cannot show a person operating in the space, and last time I checked, we cannot ‘fly;’ we walk, and stop, and sit. I am still saddened by a video fly-through I saw done by a local academic of a space whose beauty I knew well from having taught a class in it – the Frank Lloyd Wright architectural office — which seemed to me utterly to falsify the actuality I had experienced.

Also, and this is critical, when we look at an image, any image, we can only focus our eyes on it, which holds it outside us, whereas in the world, our peripheral vision allows us feel ourselves in a space. So a model would be more useful, and we are friends with Dakotah Apostoulu, a talented model maker at the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture. So even though I couldn’t go through a rabbit hole to make myself sufficiently small to go inside the model, couldn’t touch, smell and hear how it would feel when built, it would take us a ways in the direction we wanted to go. And of course we could photograph the model from various perspectives, which by mystifying scale could make it look as big as a house, if only from an outside perspective.

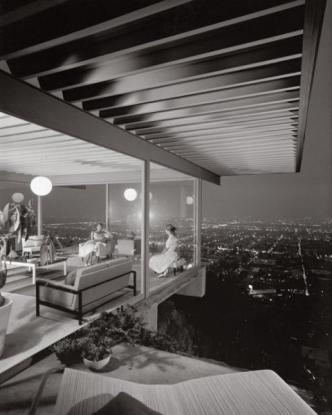

But photographs, I have come to feel, often mystify the architecture they purport to clarify. Consider the image below, which is arguably one of the most influential architectural photographs of the last one hundred years: Julius Shulman’s “case study house #22:”

The photo, published in 1960, is undeniably brilliant, and the architect, Pierre Koenig, undeniably accomplished. The photograph was one of a series published by the magazine Arts & Architecture following wartime discussions by a group of young architects, including Richard Neutra and Charles Eames.Rather humorously, the initial program announcement stated that each “house must be capable of duplication and in no sense be an individual ‘performance.’

Seen by tens of thousands of people after its publication, the series is credited with playing a significant role in making architectural modernism popular in the United States in the flush of pent-up home building demand after World War II.

Unfortunately, no one can actually see the case study house #22 house from Shulman’s perspective without a tall ladder, special photographic lighting has been employed, and the two women in it are, of course, actors.

In the years that followed, many architects, under the influence of photographers, began to design houses for the photograph.

Stewart Brand, in his How Buildings Learn, offers a withering critique of this trend.

Clare Cooper Marcus [a California architect] said it most clearly: ‘You get work through getting awards, and the awards system is based on photographs. Not use. Not context. Just purely visual photographs taken before people start using the building…. I heard something similar from San Francisco architect Herb McLaughlin: ‘Awards never reflect functionality. I remember serving on a jury one time and suggesting, ‘OK, we’ve winnowed this down to ten projects we really like. Lets call the clients and see how they feel about the buildings.’ I was hooted down by my fellow architects.

But the image problem, in our culture, lies even deeper. We live under an “unending rainfall of images” in Italo Calvino’s words, and images have become so highly developed as to cause confusion with actuality. Consider what took place when an American filmmaker was trying to create a set for a film about a man whose life takes place in a town sized movie set:

Hollywood set design simply looked too real for the 1998 film The Truman Show. To achieve the level of artificiality demanded by the script, the filmmaker turned to Seaside, Florida, a place that exudes plastic pretence. Seaside is the much publicized New Urbanist resort town planned to project the security, scale and feel of a Hollywood interpretation of small-town America…. [So] in less than a century, we have witnessed an evolution from the set as actual place to the set as an artificial, constructed place, to real places as constructed sets. The line between the simulated and the authentic is almost hopelessly blurred.”

–Maggie Valentine, “Escape by Design,” in Mark Lamster (ed.), Architecture and Film

This kind of confusion between image and actuality is in turn related to a larger shift in our culture, from a print based to an image based culture. Its effect on architecture, as the Finnish architect and philosopher, Juhani Pallasmaa has observed, has been profound:

As buildings lose their … connection with the language and wisdom of the body, they become isolated in the cool and distant realm of vision…. Architectural structures become…flat, sharp-edged, immaterial…. The detachment of construction from the realities of matter and craft further turns architecture into stage sets for the eye…. The gradual growing hegemony of the eye seems to be parallel with the development of Western ego consciousness and the gradually increasing separation of the self and the world; vision separates us from the world, whereas the other senses unite us with it.

—The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses

In response to this cultural “ocularcentrism,” Pallasmaa calls for a “re-sensualization” of architecture:

A building is not just a physical structure; it is also a mental space which

structures and articulates our experiences. Meaningful architecture houses

us as fully sensing … beings, not as creatures of mere vision. Our house

becomes an extension of our body, skin, senses and memory.

–-The Embodied Image

This makes profound sense to me, but again, how could we expect our architects to convey to us the sensual experience of occupying an actual space with the drawing and modeling tools at their disposal?

More and more, it seemed to require a gigantic leap of faith to go forward. And going forward with relatively inexperienced architects, one of whom had moved to Denver, supervising a yet to be hired contractor in rural Wisconsin, in turn being supervised by even more inexperienced clients from Boston, was this not a likely recipe for an architectural train wreck: esthetic, spiritual, financial and ecological?

This last is worth briefly dwelling on. A friend in Wisconsin, Lew Lama, an anthropologist turned stone mason and builder, put it succinctly: ‘When you build on a site, not only is there a tremendous waste of material, because you have to throw away whatever it is that doesn’t go into the house, but also of time, which is to say money. Think of weather. Half the time a house is being built, there is no one there. It is raining, or is likely to rain, or snowing, etc.’

A study commissioned in 2007 estimated a “25 to 50 percent waste in coordinating labor, and in managing, moving and installing materials” in site built housing (Tulacz and Armistead, 2007).

So the one/off, architect designed, contractor built house we had originally dreamed of now not only terrified us, but would likely be ecologically irresponsible as well. Of course we dreamed of employing all the latest sustainable technologies, including solar, etc. but even were the result to allow us to be energy neutral, the building of it could never be. And yet, in the grip of what felt like primal impulses, we wished to build a refuge on this beautiful land in the worst possible way.

Paralyzed, we terminated a design process already well underway and returned to square one.

Was there some kind of a middle ground for a middle class couple between living in a contractor designed box and in a one of a kind architectural creation which might end up alienating and/or bankrupting us, and offending the environment when it was finished?

In 2007, a pair of progressive local entrepreneurs from Boston, Bill Haney and Maura McCarthy, decided to explore the prospect of profitably designing, building and selling modular homes. Modular, or factory fabricated homes, despite having obvious ecomomic and ecological advantages over site built homes, and having become widely popular in Europe, had never really caught on in this country.

Karen and I thought we knew why, from looking at various modular home companies on the web when we first acquired our land in 2006. Most of them looked like tarted up trailers, because that’s what they were: in order to transport them to remote home sites, they had to be trailer width so as not to require “wide load” escorts and to run afoul of innumerable local transportation ordinances.

From 2007 to 2009, Blu Homes, as Haney and McCarthy called their company, built nothing. Instead, it gave a grant to the Rhode Island School of Design to study the history of modular homes in the U.S. to try to pinpoint why modular home companies had failed to thrive.

In addition to the crippling transport problems, the biggest factor, their study found, seemed to be the lack of comprehensive control over the entire production process from design to construction to delivery to client move-in. Absent that control, clients would be given one price by the designer, but the designer would not be in control of the producer, which might not in turn own the delivery company, which tended to result in ballooning costs at every stage of the process, with frequent client disillusionment at its end.

By 2009, Blu had assembled a team of MIT engineers and RISD creatives, and was ready to try out their ideas. Thanks to the recession, they were able to acquire very inexpensively several home designs by a talented California architect, Michelle Kaufman, whose own attempt to modularize her work had failed. They also were able to purchase an abandoned factory space in Longmeadow, a suburb of Springfield.

The transport problem had meanwhile been solved by Blu’s engineers, who created a folding technique for their steel framed structures employing large temporary hinges so they could build a full-sized house, then fold it into tractor trailer width pieces for delivery anywhere in the U.S. without any special transportation permits.

The houses would arrive at the site on one or more trucks, would be picked up by a crane, then lowered on to a foundation built in close consultation with the factory by a local contractor hired by the client, then “unfolded.” Accompanying the delivery would be four or five factory technicians who would make final adjustments to the house, which would arrive with electrical outlets already in place, appliances, heating and cooling appliances. In most cases, clients were able to move in within two weeks of the ‘setting’ of their house. The Blu homes come with a ‘turnkey’ price. You know what its final cost will be before it is built.

When Karen ran across their website early this year, finding several designs she liked, I was intrigued but skeptical. My Macintosh guru always said ‘never buy the first release of a new product. There will be bugs. Let others pay to find them.” Were we to buy a house from Blu, it would be the first one they delivered to the Midwest.

But what clinched it for us was we were able to visit the factory during an open house and actually sit inside a living room that closely resembled the living room in the house of theirs we thought would be most suitable for our Wisconsin site.

![]()

This modest dwelling makes no architectural ‘statement,’ and will likely never be featured in an architectural magazine. But we have been able to sit in, and touch a room which will closely resemble its living room, and found it both elegant and cozy, we know exactly what it will cost, and it will be delivered within nine months. The existential dread is gone.

Better still, during a recession, they are expanding and hiring. So perhaps my richly deserving students will benefit by finding actual architectural, if not starchitectural, work as well.