Last December, just a few days before Christmas, federal officials confirmed the news that had been expected for months: starting with the 2012 election, the commonwealth of Massachusetts will lose one of its 10 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Massachusetts is one of 10 states that will lose a representative in Congress due to shifting national demographics revealed by the 2010 U.S. Census. By law, census figures are used to apportion the 435 seats in the House among the 50 states, based on the states’ populations. It’s a simple concept: more populous states get more members; less populous states, fewer.

But how that concept gets put into effect—well, that’s where things get complicated. With the tedious work of census-taking done, now begins the high-stakes work of figuring out how to winnow down Massachusetts’ seats from 10 to nine. Or, put another way: figuring out which of Massachusetts’ 10 current members of Congress will see his or her seat eliminated—and which part of the state will find its political representation diluted.

And there’s a widespread feeling throughout Western Mass. that it’s this region that will take the hit, that, once again, the political interests of the eastern part of the state will take precedence over the interests of those of us in the hinterlands. If that turns out to be the case, the region’s two long-time congressmen—John Olver and Richie Neal—could find themselves in an uncomfortable game of musical chairs, battling each other for the remaining seat. More important, the roughly 825,000 residents of the four western counties would see their voice in Washington significantly muted, with one congressperson to represent the interests of a sprawling and diverse region.

That Sinking Feeling

That sinking feeling in the collective stomach of Western Mass. notwithstanding, it actually will be some time before there’s any official word on which district will be eliminated.

Under the Massachusetts constitution, the state Legislature must redraw congressional district lines every 10 years, to reflect the results of the most recent census. Earlier this year, the Legislature created a Special Joint Committee on Redistricting to do that job. It’s chaired, on the Senate side, by state senator Stan Rosenberg (D-Amherst); state representative Cheryl Coakley-Rivera (D-Springfield) is vice chair from the House side. (The committee is also charged with drawing district lines for Massachusetts’ 40 state senators and 160 state representatives, as well as its eight Governor’s Council members. While that process could result in some changes to district boundaries, no seats will be eliminated.)

The committee held a series of public hearings on redistricting this spring and summer, with stops in Springfield, Greenfield and Pittsfield. Its proposed district map is expected to be completed this fall; it will then have to be approved by the entire Legislature and the governor. Would-be 2012 congressional candidates will be awaiting that final map eagerly, as the election season officially kicks off on Feb. 14, the first day nomination papers are available.

“Being the procrastination palace that the Statehouse is, we’re not going to see any new maps until late fall,” predicted Matt L. Barron, a Democratic political consultant based in Chesterfield. And even after the proposed maps are approved, he noted, the process could be slowed down if any aggrieved parties sue. That happened after the last redistricting process, and some activist groups are already warning that it could happen this time. “That could really put a wrench in the process,” Barron said; depending on how quickly the courts resolve lawsuits, a final map could be delayed until the winter of election year.

As chair of the legislative committee, Rosenberg is clearly aware of the public’s anxieties about the process. His committee has taken great pains to assure residents that their voices will be heard, that the process will be a fair one. It’s also taken pains to assure them that no decisions have been made yet. “No one, not even those of us on the committee, can say at this early stage how the nine new Congressional districts will be redrawn,” Rosenberg wrote in a column in the Daily Hampshire Gazette in May.

Farm to Skyscraper

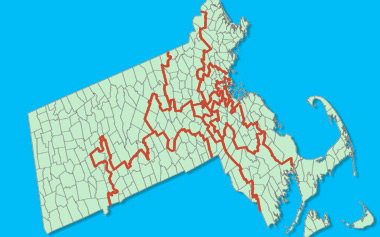

Geographically, Massachusetts’ two western congressional districts cover roughly half the commonwealth. The 1st District, represented by John Olver, a Democrat from Amherst, is the largest in the state, covering all of Berkshire and Franklin counties, much of Hampshire County, and parts of Hampden, Worcester and Middlesex counties, reaching as far east as Pepperell. It’s a largely rural district, although it does include a number of small cities, among them Pittsfield, Holyoke and Westfield.

The 2nd District, anchored by Springfield and represented by that city’s former mayor, Democrat Richie Neal, covers much of Hampden and Worcester counties and stretches to include, as its easternmost edge, the Norfolk County town of Bellingham. In a rather awkward bit of gerrymandering, the district also reaches north into Hampshire County to include Northampton, Hadley and South Hadley.

Rosenberg’s assurances aside, at his committee’s hearings in Western Mass., speaker after speaker expressed the anxious belief that it’s this region that will come out of the redistricting process the loser. Those speakers included Springfield Mayor Domenic Sarno, who made his case at a hearing at Van Sickle Middle School in March.

Losing one of its two congressmen would be devastating to the region, Sarno later told the Advocate. “Let’s face it: Congress runs on seniority,” he said. And under that system, Western Mass.’ two representatives are well placed: Olver, who has been in the House for 20 years, is the only member of the state’s delegation to sit on the House Appropriations Committee, and he chairs the subcommittee on transportation, housing and urban development. Neal has been in the House since 1989 and sits on the Ways and Means Committee, a powerful body that oversees taxation, Social Security and Medicare, among other programs.

Those key positions, Sarno said, allow Olver and Neal “to bring home the bacon. Plus, they know this area like the back of their hands. That’s key.”

As mayor of Springfield, Sarno is concerned about the possibility of his city’s being merged with a largely rural district. “It’s just completely different issues in an urban center versus a completely rural area,” he said. Urban mayors like himself, he said, rely on their congresspeople to help bring home crucial aid, like Community Development Block Grants and what Sarno calls “empowerment”—as distinguished from “entitlement”—programs. “It’s extremely important that we fight to keep both our congressmen, especially for the city of Springfield,” he said. “We are the core and hub city of Western Mass.”

Given the population data, Sarno knows some adjustments will have to be made to the existing districts. But those changes had better not come entirely at the expense of the western part of the state. “Many times we get the short end of the stick,” the mayor said. “You better be damned sure that I’m going to fight for our congressman here.”

“Children in a Peanut Gallery”

The fight to keep the region’s two congressmen suffered a symbolic but still painful blow in May, with the release of a proposed map that lumped the entire western part of the state into one large district.

That map—actually, there were two variations, both holding the same fate for Western Mass.—was not the work of Rosenberg’s legislative committee, but rather of a private group called FairDistrictsMass. A self-described “nonpartisan group of Massachusetts voters working to establish fairly drawn congressional and legislative districts,” FairDistrictsMass is the baby of businessman Jack E. Robinson. A former Republican (he recently left the party to become an Independent), Robinson’s sideline is running quixotic, losing campaigns for elected office (including campaigns for Senate in 2000, Secretary of the Commonwealth in 2002 and Congress in 2006, and, in 2009, a bid for the GOP Senate nomination that went to Scott Brown). State Rep. Dan Winslow (R-Norfolk) is the group’s legal counsel. FairDistrictsMass has declined to publicly reveal the names of donors who’ve supported its work—the Mass. Office of Campaign Finance has ruled it doesn’t need to do so—although Robinson has said he’s contributed $100,000 of his own money.

According to the group, its proposed maps take into account population figures and the desire to keep intact “communities of interest” (a legal standard that makes good sense but that, in truth, can be broadly defined to allow for political manipulation).

FairDistrictsMass’ maps have no legal authority, but rather serve to nudge the legislative committee in a particular direction. Specifically, the group is pushing for the creation of a Suffolk County district that reflects the current demographics of that area, where the majority of residents are members of racial minorities.

After the last redistricting process, voting rights activists sued, contending that the state legislative districts drawn up by the Massachusetts House illegally diluted the power of minority voters by shifting district lines in the Boston area so that black voters who’d previously been distributed over three districts were now packed into one. In 2004, a panel of federal judges found that “incumbency protection played a significant role in the Committee’s redistricting decisions,” resulting in a plan that “sacrificed racial fairness to the voters on the altar of incumbency protection.’ The judges ordered that the map be thrown out and new districts drawn.

Groups including FairDistrictsMass are already indicating that they will sue if the new map does not include a Suffolk congressional district dominated by minority voters. Winslow told the Quincy Patriot Ledger that his group’s proposed maps are “a pre-condition for litigation,” adding, “You can’t file a lawsuit in Massachusetts unless you have a map that proves you can draw a more fair district.”

There are compelling arguments to be made for creating a minority-majority district in the Boston area, especially in light of the injustices that prompted the 2004 lawsuit. But 100 miles away, here in Western Mass., there’s a sense that the maps don’t take into consideration the compelling needs of this region. Indeed, they feel like a slap in the face—made all the more stinging by Robinson’s remarks at the press conference where he released his proposals.

“I know a lot of folks out west have been clamoring to maintain the two incumbent congressmen’s districts, but the math makes that nearly impossible, and frankly there’s no reason to do that,” he said.

FairDistrictMass offers two proposed maps. (The public is invited to vote, at a cost of $2 a pop, on a favorite version at www.fairdistrictsmass.org.) The differences between the two lie in the eastern part of the state. Plan A would merge the cities of Boston and Cambridge, along with several neighboring suburbs, into one district, where minority voters would make up the majority. Plan B would also create a minority-majority district, in this case by combining most of the city of Boston with North Shore communities including Everett, Chelsea and Lynn.

On the other end of the maps, things are decidedly less nuanced. Both versions call for one new district, which lops off the western third of the state with a more or less straight line running north to south. Several communities that are now in Olver’s and Neal’s districts—Northfield, Belchertown, Granby, Ludlow—would be moved into the adjoining 8th District to the east. (In a perhaps inadvertently revealing indication of the group’s priorities, FairDistrictMass’ proposals reverse the order in which the congressional districts are numbered. Right now, they’re numbered from west to east, starting with Olver’s 1st District. On the proposed maps, the numbering begins in the eastern part of the state and ends with the large 9th District in the west.)

FairDistrictsMass’ proposed maps—and Robinson’s comments about Western Mass. in particular—”crystallized for me my concerns,” said David Gaby, manager of the Redistricting Project of Springfield’s Universal Community Voices Eliminating Disparities. The city group is part of the Drawing Democracy Project, a statewide coalition that includes Common Cause, MassVote and ?Oiste?. “How the redistricting process is carried out not only determines a community’s next elected official, but will shape decisions at the state and neighborhood level for a decade,” Drawing Democracy says. “It is imperative that all Massachusetts residents have a voice in determining how they will be represented.”

Robinson’s quick dismissal of the interests of Western Mass. was disrespectful, treating residents of this region “like children in a peanut gallery,” said Gaby. While the proposed maps carry no weight, he said, they do represent a common mindset in eastern Mass. “I think Mr. Robinson and a lot other people just don’t see why we should matter. … We’re not on their mental map.”

During a recent interview with the Advocate, Gaby was looking at copies of FairDistrictMass’ Plans A and B, hanging on his wall. When it comes to eastern Mass., there are significant, finely wrought differences between the two. But on the western end, “there’s no variation,” he noted.

“That’s not their area of interest,” Gaby said. “I don’t necessarily want them to be interested [in Western Mass.]. But I sure would like them to leave us alone.”

Diversity vs. “Super-District”

Much of the resistance to one “super-district” for Western Mass. stems from the dramatic diversity of the region, with population centers ranging from Springfield, an urban center of 153,000 residents, to tiny rural communities like New Ashford (population 248) and Rowe (347).

Linda Dunlavy is the executive director of the Franklin Regional Council of Governments, which represents the 26 municipalities that make up Massachusetts’ most rural county. She knows the specific needs of those smallest of communities—and what it means for them to have a congressperson who understands and is responsive to those needs.

The challenges include poverty; while 12.8 percent of Franklin County’s residents live below the poverty line—compared to a statewide rate of 10.3 percent—rural poverty is a “forgotten” problem, said Dunlavy. In rural areas, poor residents—and, indeed, all residents—face limited public transportation, which in turn limits access to health care, education and job opportunities. In addition, Dunlavy noted, many rural towns have a single tax rate for both residential and business properties. Because residences far outnumber businesses in these towns, that puts an especially heavy burden on homeowners. And because property values are often low in these towns, they don’t yield a great deal of tax revenue to fund necessary services.

Olver has represented the 1st District, which includes Franklin County, since 1991, when he won a special election after the death of longtime Rep. Silvio Conte. “Congressman Olver … has been really very aware and concerned about the needs of Franklin County and has really taken his responsibility to care for Franklin County quite seriously,” Dunlavy said. She pointed, for example, to his leadership in the “Northern Tier” study, which focused on economic development in that part of the district, home to many of the state’s poorest communities; to his securing of funds for safety improvements along Route 2; and to his work to bring broadband Internet access to the district, which will open new economic opportunities.

“He really is aware of the issues in rural towns,” Dunlavy said. “If we do end up with one district, there would be less attention. There would just have to be.”

She continued: “I think that, for me, there’s a difference between rural issues and suburban issues, and it does not make sense to lump Western Massachusetts into a single entity. … Hampden County and Franklin County are really different. Asking one congressional person to understand those vast differences would be a big disservice.”

A “Springfield Seat?”

If the 1st and 2nd Districts are collapsed into one seat, conventional wisdom holds that it would be a “Springfield seat.” After all, Springfield is, by far, the largest city in this part of the state and the economic and political center of the region. So if Western Mass. does find itself with just one congressperson, Springfield and its immediate neighbors would be the winners, right?

Wrong, say city activists like Gaby, of Universal Community Voices Eliminating Disparities.

Gaby has his share of criticisms of Richie Neal, a former high school history teacher who began his political career on the Springfield City Council, served as the city’s mayor in the 1980s, and was elected to Congress in 1988. But, Gaby said, “he’s done a very good job representing a pretty diverse community. If we had to compete with everybody else, I don’t think we’d do as well.”

If Western Mass. is reduced to a single congressional seat, Gaby allowed, the odds are good it would be filled by someone from greater Springfield. “But [the city] still won’t be served well,” he contended. “I think everybody in Springfield—especially those outside the power structure—would have less access to their elected representative, less access to funding. I think a lot of the positive things that have been going on [in the city] wouldn’t have the support they do now—even though we have not a lot [of support] now.”

Gaby recently spoke to a resident of the 1st District town of Hawley (population: 337), who expressed concerns about being in a district with a city whose population is roughly 450 times that of her town’s. “I can see how they’d feel dwarfed and intimidated by being part of a district with bigger cities,” Gaby said. “But it’s just not necessary.”

Indeed, Drawing Democracy is developing its own alternative congressional district map. While a final version won’t be ready until later this summer, Gaby said, an early draft shows three districts located, wholly or in part, west of I-495, including a 1st District that covers Berkshire, Franklin and Hampshire counties, and a 2nd District that includes the Hampden County cities of Springfield and Holyoke (the latter is currently in the 1st District) and reaches as far eastward as the boundaries of the existing 2nd.

Dry Math—and More

On one level, the redistricting committee’s work comes down to basic, and rather dry, math: by law, each congressional district should contain more or less the same number of residents, a number reached by dividing the state population by the number of congressional seats, as determined by the most recent census. In this case: 6,547,629 people, divided by nine seats, equals districts of about 727,514 people each.

But underneath that formula lies a deeply political process. It is, after all, politicians themselves who are drawing the district lines, and it would be naive to think that they could do so without considering their own political prospects and those of their political allies or their entire party.

Massachusetts has an especially embarrassing track record on that front; this is, after all, the place where the term “gerrymandering”—manipulating district lines to benefit a particular party or candidate—was first coined, 199 years ago. (The “gerry” comes from then-Gov. Elbridge Gerry; the “mandering” from the salamander-shaped eastern Mass. district he approved to benefit his party.) Common Cause’s website features a “Massachusetts Gerrymandering Hall of Fame,” which includes the rather tortured district now represented by Neal, a bumpy-backed creature that rears its head upward in Hampshire County to grab South Hadley, Hadley and Northampton. “The Loch Ness Monster? The Sphinx? A Camel? No. It’s the Massachusetts 2nd Congressional District!” reads Common Cause’s description.

Then there’s the fiasco from 2004, when the federal judges found the Massachusetts House district plan was drawn to serve incumbent politicians, not voters, and ordered it be scrapped. That mess included then-House Speaker Tom Finneran’s indictment for perjury after he testified in court that he’d played no role in the process, despite much evidence of his fingerprints all over it. In 2007, Finneran pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice in exchange for prosecutors dropping three counts of perjury. (Ironically, there was nothing illegal about Finneran’s involvement in redistricting—just his lying about it in court.) Finneran, an attorney, was subsequently disbarred, but don’t lose too much sleep worrying about him: he’s found a new career as a Beacon Hill lobbyist and radio talk show host.

As the current redistricting effort got off the ground, efforts were made to try to minimize political influence in the process. While the Massachusetts Constitution rests the responsibility for redistricting with the Legislature, Secretary of the Commonwealth Bill Galvin, a Democrat, suggested creating an independent, bipartisan group to draw up several non-binding maps, which would then go to legislators for approval. Statehouse Republicans backed the idea, saying it would restore public faith in the redistricting process. But a bill to create an independent commission died in the state Senate in January by a mostly party-line vote of 34 to 5.

Rosenberg, the chair of the legislative committee that was created instead, defended that decision in his May Gazette column, writing that an independent commission wouldn’t necessarily be free of political interests. “When the members of the Legislature chose to have redistricting performed by a legislative committee, instead of a so-called independent commission, we opted to keep it in the hands of people who are held accountable by the political process every two years,” he wrote. “If voters are dissatisfied with our results, it will show at the polls, a powerful incentive to do our job well.

“An independent commission, however, whose members would have been appointed by elected officials, would not have negated the political nature of redistricting, merely removed from voters the power to express directly any displeasure with an unsatisfactory result,” Rosenberg argued.

The Massachusetts Republican party, for one, has been quick to express its displeasure with the legislative committee, slamming it for scheduling private meetings with the incumbent members of Congress (all Democrats) to discuss redistricting. “What could the members of the congressional delegation have to tell you in private that they would not dare say at a public hearing?” state GOP chair Jennifer Nassour asked in an open letter calling for Rep. Michael Moran (D-Brighton), House chair of the committee, to cancel plans to meet with the members in Washington. “Out-of-state, private meetings held behind closed doors serve to fuel the warranted mistrust the people have in the House of Representatives in particular and state government in general.”

The GOP also went after Moran for planning a campaign fundraiser while in Washington at a venue, according to reporting by Boston’s WCVB-TV, secured for him by U.S. Rep. Mike Capuano, one of the Democratic incumbents who could lose his seat in redistricting. Moran cancelled the event after the news broke. “It’s amazing that neither Rep. Moran nor Congressman Capuano could see the obvious conflict of interest this fundraiser presented until after Channel 5 started asking questions,” Nassour chastised them, adding that unless the private meetings were also canceled, “we are left to conclude redistricting will be hammered out behind closed doors and the public hearings are a dog-and-pony show.”

Will Someone Please Step Down?

Their grievances in Massachusetts aside, Republicans should be pretty pleased with the national redistricting picture.

Ten states—all of which tend to vote Democratic—will lose a total of 12 congressional seats as a result of the 2010 census. The seats will be reapportioned to eight states, most of them in the South and Southwest, that saw significant population increases; of those eight, five skew Republican, according to Gallup Poll data. The biggest winner in the redistricting shuffle: Texas, which will gain four seats.

Massachusetts’ population did, in fact, increase over the previous decade: just over 6.5 million people live in the Bay State, a 3.1 percent increase from 2000. Still, that growth is negligible compared to the changes in western and southern states. Indeed, while other states grow at faster rates, Massachusetts has seen its number of congresspeople steadily dwindle since the early 20th century, when it had 16 House members. That creates an increasingly crowded field for its politicians—this year, leaving 10 incumbents fighting for just nine seats.

The best-case scenario—for those incumbents, at least—would be for one of the 10 to opt not to run for re-election, sparing the Democratically controlled state Legislature the uncomfortable task of deciding which of their fellow Democrats will have to face off against one another. (The last time two incumbents had to fight for one congressional seat was 1982, when Barney Frank, a Democrat, and Margaret Heckler, a Republican, battled for the newly combined 4th District. Frank won.)

But right now, at least, none of the Democrats is budging. While several eastern Mass. congressmen (including Rep. Michael Capuano, who lost the Democratic Senate nomination in 2009, and Rep. Stephen Lynch) are considered possible challenges to Scott Brown in the 2012 Senate election, none has yet taken the plunge—and as Brown continues to build his campaign war chest (at last count, it approached $10 million), it’s uncertain any will. At the very least, Brown’s potential challengers might wait until they see whether the new district map leaves their seats intact or forces them into contested races.

In addition, Barron, the Chesterfield consultant, pointed out, there’s talk that should Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton step down, Massachusetts’ senior senator, John Kerry, would be the frontrunner for her job. Kerry has denied interest in the position (which many expected him, not Clinton, to get after Barack Obama’s election in 2008), although the Boston Globe this winter said the senator is “running an unofficial campaign for the job.” If Kerry is in contention for the Cabinet job down the road, Barron said, the Democratic congressmen might opt to wait to run for his open seat rather than challenge the popular Brown.

There’s also been speculation that at least one member of Massachusetts’ delegation will retire before next year’s election—perhaps Olver, the oldest of the group, who will be 76 on Election Day 2012. Olver, however, has said he intends to run for re-election next year.

Complicating matters, the new district maps could, in fact, toss multiple incumbents into one district while creating other districts where none of the incumbents lives. FairDistrictsMass’ proposed maps, for instance, create a number of electoral permutations—in one case, putting Capuano, Frank and Rep. Ed Markey in one district; in another, pitting Frank against Rep. James McGovern.

“Incumbent protection is not a legal standard, so this is a legally flawless plan to maximize voter power, not incumbent power,” FairDistrictMass’ Winslow said at the maps’ release.

If Western Mass. is merged into one district, it would be Olver and Neal who’d be forced into a face-off. Who would win?

“Oh, boy. That’s a very interesting question,” said Barron, who served as Olver’s political director in the late 1990s. (He’s not working for any congressional candidate now, he said.)

Neal and Olver, Barron said, have a good relationship, supporting one another’s projects and working together on issues that affect the entire region. “But if the Legislature puts a gun to their head,” he said, “it will be about political survival.”

In an Olver/Neal contest, Barron said, the Democratic base would break off into smaller camps. Olver, from Amherst, would likely draw the most liberal voters; Neal, from Springfield, would attract the culturally conservative vote. Organized labor would go with Olver; corporate interests, such as MassMutual, would stick with Neal.

“Where would environmentalists go? Where would women go? Where would people of color go?” Barron said. “All the facets of the Democratic party would break up, and it’s very hard to predict. …It would be a real clash of the Titans.”

“No Etiquette Book”

Adding even more drama to that clash, there’s another Democratic candidate in the mix: Andrea Nuciforo, register of deeds for the Berkshire Middle District and a former state senator from Pittsfield, who in 2009 formed a committee to run for the 1st congressional seat—whatever the district looks like come 2012.

Nuciforo’s decision to jump into the race ticked off a lot of the Democratic faithful, who were unhappy with him for challenging the incumbent Olver. (Barron, the former Olver staffer, called Nuciforo “opportunistic” and said that, “absent some scandal,” he can’t imagine him beating Olver.)

“There is no etiquette book affixed to the United States Constitution,” Nuciforo said in response to criticisms that challenging Olver is bad form. “Voters are entitled to decide who will represent them in the U.S. Congress.”

Much of Nuciforo’s campaigning has focused on the issue of redistricting. He’s testified at legislative committee hearings and has an entire section on his website devoted to the topic. “The key issue continues to be whether small cities and towns that have common characteristics will be together in a congressional district,” Nuciforo told the Advocate. He advocates for a 1st District made up of rural towns and cities with populations under 50,000, former manufacturing bases that are “struggling to find their way in the new global economy.”

That could be key to Nuciforo’s electoral success. Nuciforo is a Pittsfield native with a Berkshire County political base and an ideology compatible with more liberal Franklin and Hampshire voters—neither of which would serve him especially well if he finds himself running in a district dominated by Springfield. Indeed, that would be a challenge even for a 20-year veteran like Olver; for Nuciforo, who’s not especially well known in the Springfield area, it could be an insurmountable one.

Nuciforo argues his case from the benefits it would bring residents of the region. He called the dismissive comments from FairDistrictMass’ Robinson—that, the “clamoring” of residents aside, there’s “frankly … no reason” to leave two districts in Western Mass.—”flat-out wrong.” The current structure, he said, has a “beautiful logic.”

“The city of Springfield needs and deserves a congressman focusing on the issues affecting that city and its immediate neighbors,” Nuciforo said. Likewise, smaller communities need to be a priority to their own congressperson. For instance, he said, while municipalities with more than 50,000 residents automatically receive Community Development Block Grants, smaller cities and towns must compete for the funds. “This is billions of dollars at risk every year. The 1st, I think, deserves a congressman that speaks exclusively for the communities that are going to be scrapping for that money every year,” Nuciforo said.

“Do I have a dream map? Yeah,” he said. Right now, the 1st District has around 645,000 residents—about 80,000 short of the roughly 725,000 each of the new districts will need. That number, Nuciforo said, could easily be achieved by adding in communities such as Northampton, Hadley and South Hadley (which are currently in the 2nd District, but, as he put it, “are a natural fit for the 1st”) as well as a few Worcester County towns to the east.

“The 1st congressional district is built in a way that puts together those communities of common interest. That might be lost on folks in eastern Mass., but it’s very clear to those of us in Western Mass.,” Nuciforo said.

“I suspect that our representatives and senators are getting the message that we need two seats headquartered in Western Mass.,” he continued. “Whether it resonates with the decision makers is another matter.”

*

The Special Joint Committee on Redistricting held its last public hearing in Boston on July 11. Now the wait begins. Rosenberg has said he expects a new district map to be approved by Thanksgiving.

Gaby, the Springfield activist, is not sure what to expect from that final plan. Statewide, he noted, much of the focus has been on the question of creating a minority-majority district in the Boston area, or of preserving the 5th District (home to Lowell, Lawrence, Haverhill and Methuen), which is represented by the only female member of the Massachusetts delegation, Niki Tsongas. While Western Mass. residents made a strong case for preserving two seats out here, Gaby said, “Massachusetts’ government is very Boston-centric.”

Barron agrees. While some are optimistic that having Western Mass. legislators in prominent positions on the redistricting committee will mean this region won’t be forgotten, at the end of the day, the plan still needs approval from the entire Legislature, he noted.

“Let’s face it: Stan is the Senate chair of the committee, and that’s important. But it’s 199 other people who vote on the plan, and most of them come from eastern Mass.,” Barron said.

District maps need to meet certain legal criteria, he added. “But they also have to be politically palatable to get passed.”