We are living at the dawn of the freelance world, as more and more people find themselves working as consultants, contract workers or freelancers. This change in the way we work is as profound as the shift that occurred during the Industrial Revolution.

More than 25 percent of all working Americans are, whether they want to be or not, temporary laborers, and that number will surely rise in the coming years. (According to the Freelancers Union, which represents almost 100,000 contract workers in the New York City metro region, freelancers already comprise 30 percent of America’s workforce.) Job security and nine-to-five jobs are becoming relics of the past. This year’s college graduates enter a fragile economy that offers more risks than guarantees, and far fewer jobs than applicants.

As corporations have prospered and gained flexibility, most workers have watched their futures decline. “Neoliberalism” has unlocked capital, freeing it from national borders; workers are increasingly a temporary, disposable expense. Firms can hire on a project basis and no longer need to invest in large facilities or workforces.

The larger social impact of freelancing has been well documented, but what is missing is an understanding of those businesses that encourage or are enriched by the new “gig” economy. We know little about the businesses that prop up freelancers, simultaneously nurturing and feeding off them. In fact, we tend not to think of these businesses collectively as an industry.

But we should. From consultants to self-help book authors to the rise of “co-workplaces,” which provide freelancers with social interaction, an industry has developed that serves as both freelance cheerleader and parasite. It has defined the new gig culture, and it is time we begin to understand this industry’s place in our economy.

*

On Amazon.com, thousands of books cater to the freelancer. Most are memoirs of success, more brands than books. And many are little more than glorified Powerpoint presentations. Daniel Pink’s 2001 book Free Agent Nation: The Future of Working for Yourself, part memoir, part DIY manifesto, is the model. He discusses how he wound up a freelancer and how he overcame his nervousness and embraced freelancing, which led to his great success. The book drives readers to Pink’s website, which in turn sends people to his seminars and other books.

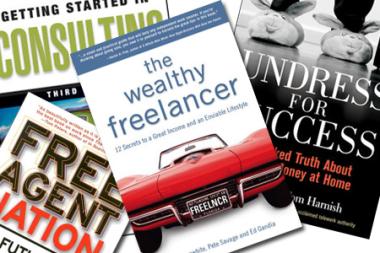

Alan Weiss’s Getting Started in Consulting is designed to introduce his audience to basic business concepts. Again, the goal is to establish Weiss as a brand, a go-to consultant and public speaker. Simple books like The Wealthy Freelancer offer a “top 12” list of things to do, much like the Rich Dad, Poor Dad personal investing book franchise. Cutesy books like Undress for Success feature bunny slippers on the cover. I could go on and on.

These books and their authors do several things. As cheerleaders for freelancing, they celebrate the freedom, creativity and inevitable success and wealth to be found in this new way to work, which is part profession and part lifestyle. What they do not do is explore the realistic possibilities of failure and the fact that most freelancers struggle. Popular freelance books suggest success is the norm: if you are not a successful freelancer, you are not normal. In other words, the old free-market arguments about social mobility from the original Gilded Age are being applied to the new workplace: if you are not successful, it is your fault.

And how does one become successful as a freelancer? Through self-development, of course. Seduced by an ethos that says we can and should improve ourselves constantly, freelancers read more books and attend more seminars on freelancing in search of success. Often the only ones succeeding are the authors and seminar leaders.

Another sector of businesses catering to the freelancer are co-work places. Freelancers can work from anywhere, or so it’s said. But many prefer some social interaction. Others do not have the space or the peace to work from home. So they share workspace. At so-called “third spaces,” such as Starbucks, a freelancer can set up shop for a small cost (usually the price of coffee).

But coffee shops are not ideal; many limit space and charge for wi-fi. To solve this problem, about 10 years ago freelance offices began popping up in most major urban areas. Some cater to subfields of freelancers, such as artists, graphic designers or those in information technology and writing/journalism.

These businesses operate much like gyms. They sell memberships (sometimes peak and off-peak) and provide atmosphere (meeting rooms, sometimes coffee), a temporary office (desk, Wi-Fi, phones and faxes) and a social setting. To be successful, they need to keep their membership rates low enough to be competitive, so they sell more memberships than there are seats with the hope that not everyone comes at once. They offer a sense of professionalism, as they know you feel better going to work at a place that feels like a mix between the university library and Starbucks.

Then there are the online businesses that connect or match freelancers to their gigs: www.elance.com, www.odesk.com and www.sologig.com. These firms match projects to freelancers and usually charge the project poster a small fee. There are other places for certain industries, like Mediabistro for media freelancers.

But in fact most freelance gigs are not found through a website, but rather through references, former employees or recommendatons by other freelancers. What these businesses more often do is connect advertisers to freelancers; their business model is based on a small income from fees and lots of ad revenue.

A new trend is evidenced by www.fiverr.com, which allows freelancers to post any service that you can imagine as long as it is at a flat fee of $5. Anne Kadet, in the June 2010 issue of Smart Money, writes, “This new era of microentrepreneur is a welcome development for the struggling employers, not to mention casual freelancers who are happy to make a little cash off their hobbies.” Some freelancers are clearly moonlighting and have more stable jobs. But most are not hobbyists. They cannot afford to sell their labor to the lowest bidder, but that is happening on many of these websites, which seem to function like eBay in reverse. Lower bids get the gigs.

*

As the gig economy expands, business models for those catering to it will become ever more sophisticated. We are evolving into a society with an atomized world of work, where we are all “rational [profit-oriented and capable of understanding the forces we are dealing with] economic men” and women. We are also, as Barbara Ehrenreich writes in her new book Bright-Sided, perpetually seeking silver linings. Those who have found a way to succeed in the freelance culture have found silver. But most are stuck in the mines.

Temporary gigs continue to displace stable jobs that were once the norm, but somehow we’re unable to see the process for what it is: another fundamental transformation of America’s economy, and thus culture. In this time of economic transition, we must ask serious questions about those claiming to aid the workers of the new economy—freelancers. Are they friend or foe?”

Richard Greenwald is dean and professor of history at Drew University’s Caspersen School of Graduate Studies. He is editing a forthcoming collection, Labor’s Day, which features essays from leading labor scholars and public intellectuals.