Like him or not, Elvis Presley is integral to American culture. The course of his career is a remarkable reflection of much that is good and much that is bad about said culture—early on, he was the embodiment of cool, blasting the sensual young world of rock and roll into living rooms everywhere. Later on, he was a cartoon, drained of his rockabilly cool and bloated on a ’70s overload of peanut butter and banana sandwiches and heaven knows what else.

It is perhaps the biggest tragedy of his legacy that Presley’s thousands of imitators focus, almost without exception, on that latter, cartoon King. If you’ve ever been to Graceland, you know that it’s hard to see where the earlier, cooler Elvis went amid the crazy overkill of the Jungle Room and the smokehouse where the Memphis Mafia liked to fire pistols.

Thirty-plus years after Elvis’ death, it’s still easy to dismiss that more common image of later years and never dig down to what made the man so essential in the first place.

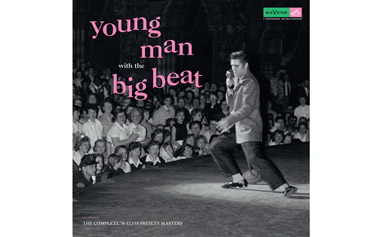

A new box set, however, reveals a very early incarnation of the King of Rock and Roll in such glorious fashion that only the most dedicated Elvis hater will be able to maintain a view of Elvis as only a sideburned tragedy. It’s called Elvis Presley: Young Man with the Big Beat (out Sept. 27), and it’s a beautiful window into the cultural moment of Presley’s exploding into America like a gyrating id bomb. This is the Elvis of screaming teenage fans, the Elvis of soft-spoken, even nervous song intros, presented in a way that makes it all seem visceral and direct.

One disc is made up of live performances, and that disc, even outside the context of the whole set, is a worthy gem. The performances sound rough in the best way, and take place in spots like Little Rock, Ark., far from the massive venues Elvis filled at the end of his life. The recordings reveal a young man who sounds a bit overwhelmed at what is unfolding—he sounds like a young upstart from a Southern backwater, fumbling a bit as he announces songs and repeats jokes (he liked, apparently, to call “Heartbreak Hotel” “Heartburn Motel”).

After the strange discomfort, something remarkable happens: melodies blast out of Presley as if he were breathing fire. It’s easy to forget just how powerful and revolutionary a singer Presley really was; you can’t avoid the energy as the words unwind.

It helped, too, that Presley, more singer than songwriter, was borrowing songs from great sources. He took Carl Perkins’ hillbilly bop tune “Blue Suede Shoes” and gave it an even more explosive life; his “Hound Dog,” of course, appears to trace back to similar tunes from African-American performers who also recorded with Sam Phillips at Memphis’ Sun Studios. Though Elvis did sometimes give credit to his sources, his status as a white man bringing very non-white sounds to audiences who might never listen otherwise is often criticized. It’s hard to believe that an overwhelmed young rockabilly rebel from Tupelo would have intentionally made that heady cultural move, but it seems clear that, regardless of intention, Elvis did serve that function. His natural charisma and monstrous talent just meant that his version of that equation was the first to catch fire.

After you settle into the familiar tones of Elvis’ big voice, other parts of the music are more easily heard. It’s here that these recordings, especially the live ones, become even more exciting. Sam Phillips was shrewd. He paired Presley with players who were also practicing a new craft. Guitarist Scotty Moore is unquestionably a seminal figure in rock history. It’s often said he invented rockabilly guitar and rock lead guitar. His talents are on display here to great effect; the live instrumental breaks flame with just as much energy as Elvis’ vocals, and Moore tears up the frets with a just-right combination of clean execution and unhinged rock energy (keep in mind, too, that “rock energy” was itself a brand new concept). Moore and Presley’s phenomenal pairing is joined to an equally solid rhythm section of Bill Black (bass) and D.J. Fontana (drums). It’s also worth noting that on some of the box set’s studio tracks, another seminal guitarist appears: Chet Atkins.

Elvis’ many fans will find much to satisfy outside the realms of studio polish or live energy, with outtakes and interviews aplenty. It all adds up to something remarkable—pop these discs into the player, and before long, you can be drawn into another time and place. The young Elvis of 1956, newly unleashed upon post-war America, offers an immediacy and raw power well worth a listen.