I stayed up way too late last night reading two articles, one about the debate over whether reducing multiple pregnancies (twins or above) down to singleton pregnancies, the other about a sperm donor with 150 children. The shared theme between these articles seems to be that when reproductive technologies began to be implemented many of the down the road questions either hadn’t yet surfaced or weren’t addressed. And weren’t regulated, either.

One of the people quoted about lack of any rules in the sperm donor article is Debora Spar. Her book The Baby Business on the economics of reproductive technology and adoption is a clearheaded and smart look into how ethics and commerce collided and the industries involve family creation. She’s President of Barnard College now (lucky Barnard). I interviewed her a few years ago and felt I’d spoken to one of the most capable and interesting people I’d ever encountered.

As a mother by adoption, issues that involve grey areas and family creation are ones I’ve thought about a lot over the past few years. I thought about them before that, too, as a reproductive justice person from adolescence and as someone whose world includes families created in pretty much every which way.

The more that we can do, the more complicated it becomes to decide what we should allow ourselves to do. I think that’s a fair principle that you could apply to any technology really. You can’t look at all this extreme weather and not think about climate change, for example, and wonder at every choice we’ve made that’s planet destroying. You can’t read about 150 siblings without thinking that someone didn’t pause to contemplate what 150 siblings means about how we view our families. When constellations can change so dramatically over time and involve so many more people, openness and conversation are called for.

The “old-fashioned” model for adoption was very, very closed. Abortion was illegal. The crisis of an unintended pregnancy included potential disgrace and infertility was barely a word uttered beyond a doctor’s office, making for an excruciating sort of privacy that really wasn’t even privacy; it was secrecy and shame. Anne Fessler’s The Girls Who Went Away is about what happened when women faced unintended pregnancies in the era when abortion was illegal. I wish every lawmaker and voter and judge had to read it.

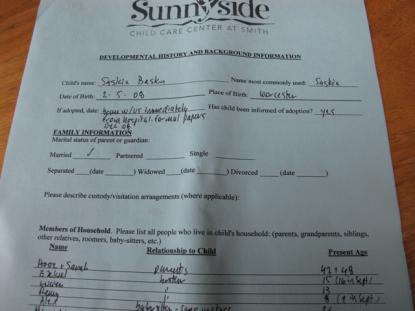

Like cleaning up the air, regulating reproductive technologies or adoption practices costs money that people don’t want to spend or not make. However, at some point, when the earthquakes lead to the hurricanes to the monsoons in very short order, maybe we don’t have a choice any longer. I think any sea change begins with people figuring out how to talk about complicated subjects, especially ones that involve our most tender feelings. I was, for that reason, gratified to see an addition on the form at our preschool this year. It asked about adoption and specifically when the adoption took place and does your child know about the adoption? We can’t have meaningful conversations without asking questions. That way, we understand where the conversation can begin. While it seems late to start talking, it’s always better to start talking than to remain silent. Things like 150 siblings don’t simply disappear if you refrain from mentioning them.