My wife and I recently spent six months traveling in the Balkans. We made stops in Spain, Croatia, Bosnia, Greece, Turkey, and had two stays in Belgrade, Serbia. As we were leaving Serbia for the first time, our landlady handed me a novel with instructions to read it if I really wanted to understand the Serbian soul.

The book she gave me was Hamam Balkania by Vladislav Bajac, a Serbian writer, journalist, poet, publisher and translator. As I read it, I discovered a work of stunning intellectual, structural and narrative complexity, written in clear, engaging and witty prose. Hamam Balkania is a novel of ideas in pursuit of age-old questions of identity and culture, and chases those questions in refreshingly unique ways.

It is the story of Bajac’s first-person, present-tense search for the nature of identity that encounters Orhan Pamuk, Allen Ginsburg, Leonard Cohen and Zen Buddhists. It is also a “historical novel” that traces the journey of Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, a Bosnian forced into servitude and Islamic conversion as a teenager in the 1500s by the Ottoman Empire, who ultimately rose to the highest positions of power under three Sultans. Bajac expertly weaves these disparate characters, story lines and time periods into a fascinating and compelling meditation on identity, culture and literary conventions.

Hamam Balkania is the latest achievement in Bajac’s remarkable career; the book won the Balkania Prize for  best novel in the Balkans in 2008, was long-listed for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award and won the Hit Liber Award. Over the course of his career, he has also won the International Itoen Haiku Poetry Contest twice, been an award-winning columnist and started a publishing company, Geopoetika Publishing, to bring translated international literature to Serbia.

best novel in the Balkans in 2008, was long-listed for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award and won the Hit Liber Award. Over the course of his career, he has also won the International Itoen Haiku Poetry Contest twice, been an award-winning columnist and started a publishing company, Geopoetika Publishing, to bring translated international literature to Serbia.

During my second stay in Belgrade, a friend fortuitously invited me along to a talk by Bajac. There, wearing his publisher hat, he spoke about the Serbian Prose In Translation (SPIT) program to a group of visiting American college students. The SPIT program is an independent program to bring translated Serbian works to the English speaking markets started by Geopoetika Publishing with support from the Serbian Ministry of Culture.

SPIT is an attempt to introduce the English-speaking world to Serbian literature. Supported in part by the Serbian Ministry of Culture, Bajac hopes to expose the global literary community to the challenging and innovative literature being produced by Serbian authors by publishing five translated selections of Serbian literature in English-speaking countries each year. The goal is to showcase the diversity and quality of Serbian authors, and for Serbian writers to become part of the global literary conversation. Open Letter Books, a publisher of works in translation at the University of Rochester, will publish one of the books from the series, The Cyclist Conspiracy, by Svetislav Basara, in March, 2012.

SPIT faces many road blocks to entering English-speaking markets: media coverage of the 1990s wars damaged Serbia’s international reputation, sufficient funding is always a challenge and the works are not intended to be the type of blockbuster popular fiction that dominates so much of today’s publishing industry. Perhaps most daunting, not just for SPIT but international literature as a whole, is that only 3% of the books published annually in English are translated from a foreign language, according to the University of Rochester Three Percent Blog.

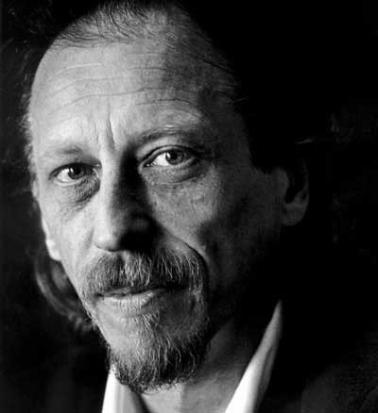

I spoke with Bajac in late July in his book-lined office in Belgrade about the risky structure of his latest novel, the gauntlet a “lesser-spoken language” faces in entering the English market and the leftover negative perceptions from the wars of the ‘90s Serbian literature needs to overcome.

*This interview has been edited and re-sequenced for clarity.

Q: You took some very bold narrative risks in your most recent novel, Hamam Balkania. You write at the beginning of the book that you are pursuing the question of identity and you use both present and past-tense, first person and third person narrative voices, as well as dual storylines–one set in the present and one set in 1500s Ottoman empire–to find answers. How did you come to weave such a complicated story to answer such a difficult question?

A: I was very aware of the risky path I wanted to go. In the book, I am talking about exploring the ideas of spreading identity and of mixing cultures. I asked myself what would happen if I could put in one novel, very literally, the historical side of the story and the present side of the story. I wanted to say that there are different ways to show the issue of identity and mixing cultures. It sounds like it could be a very kind of artificial work but I said okay, I’ll take a risk.

I always tried to write on the issue of identity by showing one person going his own way but this book is connected to many more historical characters and living persons. I used historical persons as examples that living within two cultures or religions was possible. I wanted to say that this is the proof; they lived that life.

But the contemporary side of the book was a way of saying that this issue is still there- everywhere, absolutely everywhere. What is the conclusion? I don’t know the answer, but I wanted to make it a part of the game.

This risky way was a bit brave because it included other difficult issues as well: addressing the very negative myths about Serbs who became Muslim [during the Ottoman Empire]. There is this idea that they are traitorous, for example. It is still a big issue in the Balkans, in the Ex-Yu, in Serbia today.

I think I reached something that I have never reached before in any book I wrote. However, the book is not only written by the author, it is written by the reader as well. You can’t say that you’ve finished the writing of the book until it is read well.

The consequences of those ideas are still unknown to me, which I like.

Q: You frequently address the complexity surrounding questions of identity in the former Yugoslavia in your work. When you talk about your own identity, which do you mean: Serb identity or Ex-Yugo identity?

When you ask me, what is my identity, I shouldn’t say that I don’t know, but the truth is I am not sure. It is not easy for me to answer. I belong to a generation that has no homeland anymore; the first one, the homeland of my childhood, is gone.

I am a Serb if you ask me directly. There were formally six nations in Ex-Yu, so the question of genes and such things in my generation is pretty complicated. For example, my wife was born in Croatia, her father is a Hungarian Yugoslav, her mother is Slovenian, and I am a Serb. What are our kids then? They are Ex- Yugoslavs, they can’t be anything else, okay. But, if we are looking in a conservative way, I am the father so they are Serbs.

In literature, you write on the basis of the whole of your life. It is not an issue of only the past or the present and not of only the future. That is why I wrote books on the issue of identity- to try and find parts of answers to that question for myself. I am not quite sure that I found enough answers yet.

Q: What is the philosophical idea behind the SPIT (Serbian Prose in Translation) Program? How did you decide which books to include?

We started this with the very humble idea of “let’s try to show what we have.” And if we have any reactions from the world, we will be more objective in understanding our own literature. That’s a question not only on the quality of our literature but of our identity as well. Until we compare ourselves with others we do not know who we are.

We choose primarily the books that we think are good literature. Then again, we choose books as different from each other as much as possible to show a wide cross section of Serbian literature.

What we’ve come to understand from SPIT is this: not that we are one of the best literary nations in the world but that we are interesting enough. The positive critical reaction to the styles and the poetics among Serbian authors shows not only that we are different within the larger literary world, but also that we are different among each other. You have nations whose literature is all very similar. Okay, it’s dangerous to generalize but you know what I mean.

This is not the case with our literature; diversity is the main characteristic of literature in Serbia. We still have more books to show the world, even though this is a small country, with a small number of people. We feel that we are equal to other cultural nations, including the United States. That’s why our work must be shown to the world.

I am not talking about getting famous bestsellers; that is an entirely different kind of writing. But we have to try to get into these markets because our so-called “heavy mental” literature deserves to be read as well. The financial mathematics might not be there but the numbers of readers are.

The literal meaning of the word SPIT is a joke too. It’s like being named an ambassador. You never know when a politician says to someone, I am going to make you an ambassador, is it a praise or is it a punishment? Because it sounds like praise, but then again, it says I don’t want to see you around here. You are expelled from the country, kind of in a nice way. So SPIT is in the very same way a joke in that, “these are the authors we spit out.”

Q: It must be exciting for new and young Serbian writers to see doors opening to the larger world.

Yes, of course. We are trying to do good things for Serbian writers. The only embarrassing thing is that I feel like a judge, which I don’t like. It’s a responsibility that I don’t need. People generally respect our choices but you can’t avoid the jealousy of some authors who would like to be translated into English, but they don’t understand that it is not only a matter of my decision. It’s a lack of money. We would do a wider program of books if we had more money. But it is not possible.

It is a pity for some of the young authors. We will have more young authors in this series; I insisted upon it. But you have to be very careful with young authors. We’ve had some experience with very talented writers who stopped writing after their first book. You have to choose ones that are promising enough. We have an author in this series with a debut novel. It’s a risk but I am an experienced guy. I think this guy is promising not only as a talented writer but promising in that he is going to write another book.

Q: Your book, as well as the other books in the SPIT program, is intellectually complex and has a complicated narrative structure. Is there a risk that complexity and intellectualism gets lost in translation?

Of course there is. I was afraid because it is a complicated novel and not easy to read in the original Serbian. I was concerned not only with the Serbian language but my creative language, understanding what I was trying to say. There are a lot of things going on, a lot of characters and situations.

But I knew Randall Major (the translator). He taught my books at the University, which I didn’t know. I knew how he translates and I knew that he liked my books. So it was not only a matter of language knowledge. Since he loves books and my work and he is a very talented translator, I was quite sure that there wouldn’t be any misunderstandings in translating.

As for the other books, we have a great literature translation department at the University of Belgrade with more than twenty departments for translation of I don’t know how many languages. It’s a very good school for that. The very first book in the SPIT series will be published by Open Letter Books in the United States in the March of next year. They use our translation of the book to be published as the American edition. So that is proof that the quality of translation is there.

Q: There must be frustration in realizing that there is this unique collective voice that’s not being heard on a larger scale. What is it like struggling to break into the English speaking markets?

It is not a nice feeling. We have a fate that is similar to many lesser-spoken languages in the world; we are not the only one. That’s comforting but that’s not good enough. We have to believe that it is possible for our literature and our language to be heard. Why should other lesser-spoken languages be introduced to the wider-spoken language audiences and not ours? Is it neo-colonialism or what?

Sometimes I know what the shortcut to getting published in English is. They find, for example, an Asian writer, but instead of translating his books, he is asked to become a citizen and write in English. So he will become an American or British writer. And that’s how English-speaking countries get fresh blood and brand-new authors; not by translating the books but by translating the author into their culture.

Q: In Hamam Balkania, you say that there is a Balkan identity forged by Western media, mostly by the wars of the 1990s. What have you had to do to counter the misconceptions and misunderstandings created by western media about Serbs and Serbia?

The issue of the wrong image of the Serbs in this way is connected to the politics. In the so-called cultural politics, I shouldn’t say that we made mistakes because we didn’t have any cultural politics. That’s the main problem. We were not there to show the world what we have culturally, who we are.

That’s the thing we should have done but didn’t. It’s a horrible mistake because in culture, as in politics, if you don’t use it someone else will. We had that problem in Ex-Yu in the 1990’s; the media war was there on the side of Muslims, on the side of Croats, Slovenians, whoever, but not on the side of the Serbs. We were very primitive in not understanding the essence and importance of the media war. And we can’t get that back. That’s why we are punished.

The state was not organized to do something about the consequences of our failure. I had to push the state as well. I said to the ministers in Serbia, “I am not asking you to assist this project, I am demanding that you assist this project because that’s what you have to do.” I think they understood the message.

Now the cultural part of Serbia has to do a diplomatic job, do a part of the politicians’ job. That’s why we do [SPIT] as a partnership with the ministry of culture. It’s not only because of the money; it’s a very important reason but not the main one. Now that we are seeing some of the consequences: Serbian books are being published in all sorts of other languages besides English around the world.

I am not here to explain the political mistakes that Serbia made. It was there and it is still there. Our task is something else: not to show us as a brilliant nation of culture but to simply show who and what we are and to leave the judgment to others.

Q: What do you see for the future of Serbian Literature and cultural identity in the world at large?

Well, I don’t expect to see a revolutionary scene led by Serbian authors. I do expect a very humble, just an ordinary, normal situation of seeing some Serbian authors accepted in English speaking areas.

It’s already like that in other languages. Serbian books are being published all over the world, in different languages so it’s already going on. The last fortress is the English language. It’s a paradox because it is a huge language and a huge place with lots of money and education and they don’t see what we do. It’s a pity. I am not that powerful– we will do what we can do. It’s our job to try to connect to some other institutions and we will try to do more and more.

But I don’t have the physical time to promote this. Who is going to do that? I don’t know. Doing this publishing is too much for me because I can’t write. I don’t have the time and energy anymore. I am over-stretched. In my head I have a lot of energy and ideas but there’s only twenty-four hours in a day.

PHOTO: Courtesy of Vladislav Bajac; Promotional use only.