As I write this morning, wheels are turning in Brockton on a project that began for me almost five years ago. Ten-by-twelve-foot vinyl banners are being printed and rigged for hanging on the faces of downtown buildings; the buildings’ landlords are getting ready for the bucket trucks to install the banners; and I am holding my breath.

Brockton is my home town. I was born and raised there, as were my father and his father. My great-grandparents had come from Ireland in the 1800s and found work in the city’s world-famous shoe industry.

I went to Brockton schools, graduated in 1985, and left for college; although my parents have stayed, I have never returned there to live. My experience of the place has since been filtered through what I’ve heard people say and what I’ve read, both of which have been mostly negative.

I knew that manufacturing had dried up, other jobs were scarce, and white flight, combined with newcomers from the developing world, had dramatically changed the landscape of my childhood. But what surprised me when I looked back at my native city was the anger that’s accompanied the changes: Brockton’s a dump. It’s become like a third-world country. Worst of all: The blacks have ruined my city.

I had been working as a photojournalist since the 1990s and, after the birth of my second child, I decided to take on Brockton as a subject: to explore the 21st-century version of the old place. Through photographing the people who live there, I was able to see past the lore and the prejudices to the individuals who now call themselves Brocktonians.

Over the past five years, I’ve returned with my camera regularly, looking up family friends and finding ways to meet people who had come since I had left. I photographed members of my parents’ circle – long-time Brocktonians with Irish, Italian, Greek, and Lebanese roots – and immigrants newly arrived from such places as Haiti, Cape Verde, and Guinea-Bissau.

Last summer I met with Jill Wiley, then the head of the Brockton Cultural Council, who had appointed me as Brockton’s Artist in Residence in 2010, to develop my work. We wondered about the best way to present to the public the photographs I’d made. We discussed a gallery show, with wine and prestige, but questioned the relevance of such a venue for all the people I’d portrayed, many of whom live below the poverty line.

We were sitting at Jimmy’s Donuts, looking out the big window at the sidewalk bustle of Brockton: so many travelers getting on and off buses, or simply trudging with their loads of groceries and laundry. Against them stood many decayed, abandoned, downtown buildings.

Jill said, “Look at those boarded-up windows – they’re perfect picture frames! And look at all these people walking past. Why not do the exhibition here?”

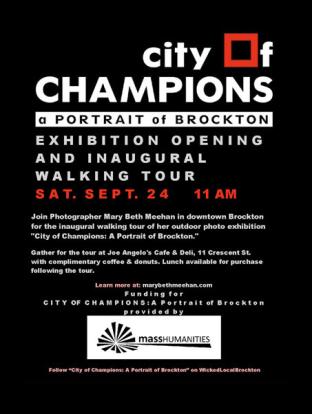

Her idea sparked a communal effort to turn Brockton’s heart into a vast exhibition: both to honor all Brocktonians and to ignite reflection on where the city has come from, where it’s going, and who has the right to call it home. We made presentations to the mayor, the city council, the Downtown Business Association, and the local newspaper. I met with Corey Dolgon, director of Stonehill College‘s Center for Community-Based Learning, who devised a way for Brockton schoolchildren to engage with – and augment – the photographs. I alerted the photographs’ subjects, and pounded the pavement to win over the buildings’ owners. And, with gratitude, we received the necessary funds from the Mass Humanities.

It’s one thing to show photographs in a place that is unrelated to their subject, such as a museum. It’s another thing to bring those photographs home: to ask the people portrayed and their neighbors to reflect upon their world. One Brockton portrait that I love is of a West African immigrant who wanted to be photographed but feared being identified. He and I decided that he could partly cover his face, so he went into his bedroom to find a blanket, but then lay down on his bed and pulled up the bedspread, on which was printed the American flag.

It’s one thing to show photographs in a place that is unrelated to their subject, such as a museum. It’s another thing to bring those photographs home: to ask the people portrayed and their neighbors to reflect upon their world. One Brockton portrait that I love is of a West African immigrant who wanted to be photographed but feared being identified. He and I decided that he could partly cover his face, so he went into his bedroom to find a blanket, but then lay down on his bed and pulled up the bedspread, on which was printed the American flag.

“He looks sick!” said one city official. “Are you trying to say that all immigrants in Brockton are sick?”

“By showcasing this picture,” said a local arts advocate, “you are throwing salt in the wounds of Brockton!”

“This picture is my favorite,” said a Brockton businessman, himself an immigrant. “It is so sad, and yet within it, there is so much hope.”

I have learned that the special gift of Mass Humanities is that, with their support, we will be able to invite people to talk about how this work makes them feel. By getting the viewers to speak and be heard – respected – we might strengthen the tie between the art and the community that inspired it. The result, I hope, will be the community’s enhanced understanding of itself.

One of my favorite Brockton photographs is of a high-school clarinet player, whose parents came from the  Dominican Republic. At the girl’s graduation, the principal exhorted the graduates to hold their heads high when they told people they were from Brockton. It broke my heart that she felt she had to say this as she saluted these hard-working students, who for all their good intentions would doubtless face negativity about their home town, and even themselves.

Dominican Republic. At the girl’s graduation, the principal exhorted the graduates to hold their heads high when they told people they were from Brockton. It broke my heart that she felt she had to say this as she saluted these hard-working students, who for all their good intentions would doubtless face negativity about their home town, and even themselves.

We all know that old manufacturing towns struggle against poverty, ignorance, and violence, and I’ve tried to address these in my photographs of Brockton. But I’ve also tried to capture the many Brocktonians, no matter where they came from, who work overtime to raise their children and lead decent lives. If only they had the shoe factories to employ them, as did my 19th-century great-grandparents.

The tragedy is when a city’s economic decline causes prejudice and fear – specifically, of newcomers. The community loses sight of people as fellow human beings, most of whom want the same things, starting with a job. There have always been immigrants to Brockton, and I hope that my photographs can help establish a bond between the newcomers of old and those of today – the Irish politician and the Cape Verdean schoolboy, the Greek doughnut-shop owner and the Dominican musician. Only if we push these cross-cultural connections can we see each other as belonging to the same place.