“I believe in God who made of one blood all races that dwell on earth. I believe that all men, black and brown, and white, are brothers, varying, through Time and Opportunity, in form and gift and feature, but differing in no essential particular, and alike in soul and in the possibility of infinite development.” –W.E.B. Du Bois, Credo

As a slogan, “information wants to be free” has a deep appeal for those of us who work in the information industry — not to mention to those of us who rely on information for our livelihood. Intuitively, we are drawn to the utopian ideal of a world in which words and thoughts can be shared without limit, in which knowledge can be spread for the public good despite the artificial constraints imposed by an increasingly dysfunctional system of copyright and patent law or by the fears of the powerful. While nothing may ever be quite so simple as the ideal, the world that archivists make does often tend toward the principle of freeing information as much as possible, even in this profit- and power-mad world.

This summer, the Department of Special Collections and University Archives of the UMass Amherst Libraries (SCUA) went live with Credo, its first full-fledged online digital repository. Fittingly, given the focus that SCUA has on documenting the history of social change, the first collection to appear in Credo is the massive collection of the papers and writings of W.E.B. Du Bois, one of great intellectuals and activists of the twentieth century and the architect of Pan-Africanism, the proponent of the talented tenth, and an unrelenting advocate for social justice in all its manifestations. In fact, the very name Credo derives from Du Bois’ 1904 essay by that name, an “affirmation of faith” and a call to a radical commitment to the principles of racial pride; of peace, liberty, and equality; of service and education; and to the virtues of patience, abiding patience.

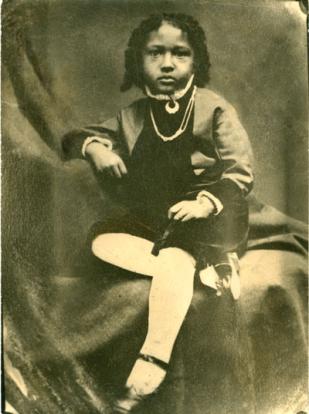

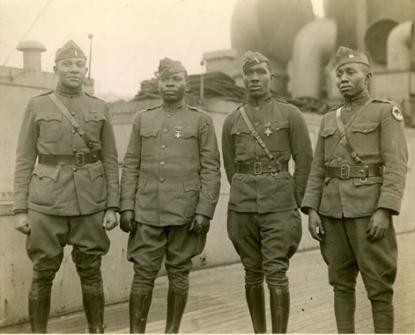

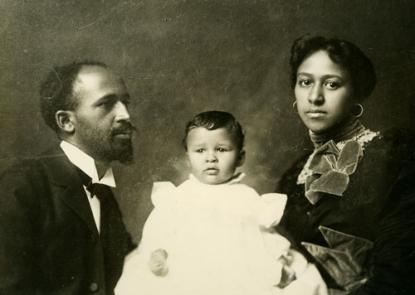

With the collaboration of the estate of David Graham Du Bois, and generous grant support from the Verizon Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities (nothing is truly free, the cynic would say), SCUA has been digitizing Du Bois’s papers from start to finish and making the results available online through Credo as we go. We are currently a little more than halfway through this four-year project, but already, researchers have access to many hundreds of photographs and tens of thousands of scans of letters, virtually every letter Du Bois wrote or received from his birth in 1868 through the Second World War. With patience, virtuous patience, researchers can find what he wrote about the founding of the Niagara Movement or the NAACP, about his study of African American soldiers in the First World War, about his thoughts on imperialism, the Great Depression, or education. Better yet, in barely two years more, we plan to see the full fruits of our labor: everything in the Du Bois collection will be online: every letter, every essay, every book, every scrap of paper.

every letter Du Bois wrote or received from his birth in 1868 through the Second World War. With patience, virtuous patience, researchers can find what he wrote about the founding of the Niagara Movement or the NAACP, about his study of African American soldiers in the First World War, about his thoughts on imperialism, the Great Depression, or education. Better yet, in barely two years more, we plan to see the full fruits of our labor: everything in the Du Bois collection will be online: every letter, every essay, every book, every scrap of paper.

If there is one constant in Du Bois’s nearly century-long life, it is his insistence that the fundamental problems of social justice that confront us are not easily constrained by borders, nor are the problems isolated unto themselves. Du Bois understood that the racial inequalities that afflict us are intertwined with inequities rooted in economics and gender, and he knew that the struggle for dignity in the United States was inseparable from the demands for dignity of colonized people the world round. Information, I am sure he would agree, wants to be free, and through Credo, we hope to bring the thoughts of this extraordinary man, in all their complexity, to anyone, anywhere in the world, at any time who is engaged in the struggle for justice. To spread knowledge born of hard struggle, to share words of hope and encouragement, words to help the oppressed wherever they may be to see that their cause is ours, and ours theirs, seems a very Du Boisian thing.

Soon, Credo will expand to include other digital collections held by SCUA, including the records of many others who have committed their lives to the cause of social justice. The vision may be utopian, but we hope through Credo to contribute to a larger conversation by setting many other collections against Du Bois, by gathering together the words of people of various stripes and persuasions from various places and times, all concerned about what makes a society just. And the information, we are sure, will want to be free.

All photos are used courtesy of the Department of Special Collections and University Archives of the UMass Amherst Libraries

Photo captions, top to bottom:

W.E.B. Du Bois as a child

Founders of the Niagara Movement

WWI Soldiers

Family portrait of W.E.B. Du Bois, Nina Du Bois, and their son Burghardt