In the very early months of Saskia’s life, it seemed as if during every visit we made together to Whole Foods—tiny little babe bundled in the fleecy sling or Moby—I met fellow adoptive parents. In fact, one friend was in the midst of an adoption process—international in her case; in any case the word process really does always apply—and I counseled her if she wanted to talk about adoption, the best place to go was Whole Foods. Both of our families are in Shelly Rotner and Sheila Kelly’s book entitled I’m Adopted! I wrote about some other picture books focused upon adoption this week for Babble (click, read, comment, share).

I’d long had friends whose families were created via the foster care system, yet the issues surrounding foster care were put into much sharper focus when I met Judy Cockerton, whose passionate desire to change the conversation about foster care has yielded much more than conversation: there’s Treehouse Communities, a Sibling Sunday program and Camp to Belong serving siblings separated within that system—read: more process—in order that they may maintain connection. She’s also supported and promoted and created a great deal of essential conversation—especially to legislators and the media.

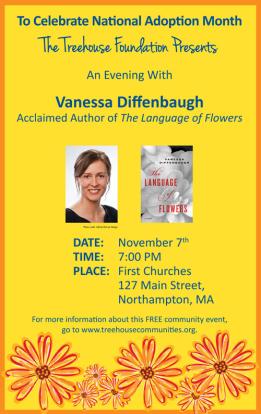

Vanessa Diffenbaugh has written a novel that chronicles a journey within the foster care system entitled The Language of Flowers. She’s giving a reading in Northampton (attention locals, please come) and in anticipation of her reading I was able to ask her a couple of questions. I hope that even if you can’t attend, learning a little about her makes you want to read more. I was moved to tears by this essay of hers about how her family doesn’t look the way she, her boy’s auntie or the judge might have envisioned.

I’m really curious how you make decisions about what is art and what is activism–how you balance those pulls.

I set out to write the best novel I could write. I never thought of it as trying to send a particular message. In fact, I imagine that if I had been trying to make a statement, the novel would probably have felt much more preachy and a lot less genuine. So, all this is to say, I started with the desire to create art–and when I began to see that readers had made an emotional connection with my character and felt moved to action, I decided to use my book to create a movement of people dedicated to creating positive change.

I’m also interested in your writing about foster care both as a fiction writer and as a mother/nonfiction writer/advocate–how you decided to do all of it rather than a single angle.

All the aspects of my life flow from my passions two passions: writing and working with kids. I’ll admit that I did not see how they would all fit together at first, but looking back now I am reminded of something a professor once told me. The portal to the universal, he said, is through the particular. Working in a university setting, he knew better than most that all the studies, evidence, and statistics in the world, no matter how illuminating, are not enough to sway public opinion or mobilize a movement. It is stories—both real and fictional—that can captivate hearts, change minds, and, in the most powerful examples, spur action.

How did you become involved with re-envisioning foster care and acquainted with the work of Treehouse?

My husband PK is studying at Harvard with Harry Spence, the former Child Welfare commissioner. PK told Professor Spence about Camellia Network and asked if he had any recommendations of people with whom I should speak. Harry Spence had a very short list, and Judy Cockerton, the founder of Treehouse, was at the top. We were certainly meant to meet, because before I had time to reach out to her, she had read my book and contacted me on Facebook! I am in awe of the work she is doing. If my family and I were planning to stay in Massachusetts permanently, we would consider moving to Treehouse!