With GOD’S JURY, Vanity Fair Editor at Large and former Mass Humanities board member Cullen Murphy has written a worthy successor to his widely praised ARE WE ROME? Like the earlier book, GOD’S JURY provides a learned yet accessible angle on the past while illuminating its connections to the present. Those who enjoy Murphy’s erudition, his intriguing asides and dry wit will not be disappointed with this latest effort.

A book subtitled The Inquisition and the Making of the Modern World that nevertheless comes in at a mere 250 pages is not intended to be a complete history of the Inquisition. Most accounts of this sorrowful chapter in the history of what we euphemistically refer to as Western Civilization run to several volumes. It is not even “a brief history” in the style, say, of a Bill Bryson, although the two writers have much in common. What Murphy excels at is weaving engaging and economical narratives of history-shaping events, threaded with quirky but fascinating observations, and demonstrating their relevance to our own time.

In GOD’S JURY we learn first of all that there was not just one Inquisition but three, separated in both time and place and stretching over seven centuries (which makes you wonder about the subtitle of this book). The first, the Medieval Inquisition, began in Southern France in the 12th century and was a fairly localized affair. The second – the Spanish Inquisition – is perhaps the best known. Like the Spanish Empire, it eventually spanned the globe. But it took place primarily on the Iberian Peninsula, is associated in our minds with the dreaded Torquemada and the expulsion of the Jews (although its principal targets were Protestants), and endured for three and half centuries. The third was the Roman Inquisition – the offensive arm of the Counter-Reformation and a vain attempt to hold the forces of scientific enlightenment at bay that lasted well into the 19th century. It ended only in 1870 with the capture of the Papal States and the founding of modern Italy under King Victor Emmanuel III.

The best known victims of the Roman Inquisition were the freethinking Giordano Bruno, who was burned at the stake in 1600, and Galileo Galilei, who was condemned in 1633 and, rather less dramatically, forced to spend the last eight years of his life under house arrest. While thus confined he managed to write one of his most important books, Two New Sciences.

The best known victims of the Roman Inquisition were the freethinking Giordano Bruno, who was burned at the stake in 1600, and Galileo Galilei, who was condemned in 1633 and, rather less dramatically, forced to spend the last eight years of his life under house arrest. While thus confined he managed to write one of his most important books, Two New Sciences.

Galileo’s heresy was the espousal of Copernicus’s heliocentric theory. He was spared Bruno’s fate because he recanted. It goes without saying that he did so under duress. Legend has it that after denying that the Earth moves around the Sun, the astronomer was heard to mutter under his breath, “And yet it moves!” – thereby recanting his recantation. Murphy notes that there is no actual evidence that Galileo ever said this but goes on to point out, with characteristic humor, that the finger bone of Galileo on display in the Florence museum that bears his name is “without question a middle finger.”

Besides being instigated and prosecuted by the Roman Catholic Church or its surrogates, what the Medieval, the Spanish and the Roman Inquisitions had in common were “a set of repressive procedures, targeting specific groups, codified in law, exemplified by severity, sustained over time, justified by a vision of the one true path, backed by institutional power.” Once these characteristics are brought to light, Murphy argues, inquisitions are “not hard to find.” Even in our own time.

Some of the most captivating sections of GOD’S JURY are Murphy’s reportage of his own encounters with the primary documents of the Inquisitions – in the Vatican Archives and elsewhere – and the personalities responsible for their interpretation and safekeeping. One such account, in a chapter entitled “The Secular Inquisition,” describes a conversation with Eamon Duffy, an historian of the early modern period in Magdalene College at Cambridge University, whose work focuses on the forced conversion of England in the sixteenth century from a Catholic country to a Protestant one. The passage begins with a meticulous description of Duffy’s cramped and book-strewn garret, down to the teakettle on the stove and the bottle of Jameson’s on the corner table.

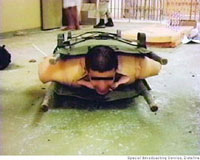

“What makes religious persecution so shocking to us, I suppose,” Duffy tells Murphy, “is that cruelty in the pursuit of the things of God seems particularly outrageous. I’m not sure it’s any more outrageous than protecting democracy with, you know, waterboarding. Systems find ways of protecting themselves, and ways to justify these things to themselves.” [emphasis added]

“What makes religious persecution so shocking to us, I suppose,” Duffy tells Murphy, “is that cruelty in the pursuit of the things of God seems particularly outrageous. I’m not sure it’s any more outrageous than protecting democracy with, you know, waterboarding. Systems find ways of protecting themselves, and ways to justify these things to themselves.” [emphasis added]

We see where Murphy is taking us – Guantánamo, the Patriot Act, extraordinary rendition, summary deportations, the Surveillance State. Murphy demonstrates clearly that what he calls “the inquisitorial impulse” is still with us. (Surprisingly, he makes no mention of the McCarthy hearings which, except for the absence of physical punishment, display in abundance the defining characteristics of an Inquisition.) “When it comes to inquisitions,” he writes, “a concise way to describe the modern world would be: fertile soil. Plant an inquisition, and it grows.”

extraordinary rendition, summary deportations, the Surveillance State. Murphy demonstrates clearly that what he calls “the inquisitorial impulse” is still with us. (Surprisingly, he makes no mention of the McCarthy hearings which, except for the absence of physical punishment, display in abundance the defining characteristics of an Inquisition.) “When it comes to inquisitions,” he writes, “a concise way to describe the modern world would be: fertile soil. Plant an inquisition, and it grows.”

Whether we are painfully aware or blithely unaware of the presence of this impulse in our own time, it is undeniably here. When it is allowed to express itself, the outcome is invariably something shameful and ignoble. The reading of history helps us better understand the challenges of the present. Reading GOD’S JURY persuades us that the obverse can also be true. When it comes to inquisitions, appreciating the present helps us understand the past.

PHOTOS:

(1) Galileo’s finger on display at Museo Galileo in Florence, Italy

(2) An early modern illustration of “the rack”

(3) Photo from Abu Ghraib, Special Broadcasting Service, Dateline