I was born in Memphis, Tennessee. Likewise, my parents, their parents, and their parents’ parents were all born in the Mid-south region of the US (western Tennessee, northeastern Arkansas, northwest Mississippi, and the Missouri Bootheel). I spent my early years in New Jersey, then my family moved back to Tennessee when I was in high school. I came to Massachusetts for college. I’ve lived in the Pioneer Valley since I graduated college. While my southern accent is a ghostly lilt on my vowels, and I’ve called the Pioneer Valley “home” for nearly 17 years, I still think of myself as a Southerner.

I was born in Memphis, Tennessee. Likewise, my parents, their parents, and their parents’ parents were all born in the Mid-south region of the US (western Tennessee, northeastern Arkansas, northwest Mississippi, and the Missouri Bootheel). I spent my early years in New Jersey, then my family moved back to Tennessee when I was in high school. I came to Massachusetts for college. I’ve lived in the Pioneer Valley since I graduated college. While my southern accent is a ghostly lilt on my vowels, and I’ve called the Pioneer Valley “home” for nearly 17 years, I still think of myself as a Southerner.

My southern sensibilities are evident in my food and cooking preferences. I am a master baker of red velvet cake and chocolate pie. Similarly, my stories and superstitions have southern roots. I make sure my husband and kids eat black-eyed peas, collard greens, and cornbread on New Year’s Day. Kale’s great, but I say, “eat more collards.” A broom is both a tool for cleaning the floor and a ritual item for weddings. I’ve always thought of these rituals and superstitions as unique to South, but over the years, I’ve come to discover that many cultures share similar traditions. For example, “jumping the broom” is generally considered an African American wedding tradition; however, it also has Celtic and Welsh roots. It is difficult to discern whether the tradition emigrated here from Africa with slaves or from Europe with slave owners. It terms of American history, I don’t think it really matters. Jumping the broom has become an American wedding ritual used by people of different ethnicities to symbolize their unions and offer respect to their ancestors. At this point in our history, no single group can claim sole ownership of the ritual. As Americans, we can claim this as a piece of our history that derived from an unfortunate collision of cultures. Jumping the broom may represent different experiences, but it also represents shared human experiences: the union of two people and the creation of a family.

I started writing tabletop roleplaying games, or RPGs, in 2006. Essentially a roleplaying game is a collective creative pursuit, a form of interactive and shared storytelling. Each player participates in creating the setting and her character. Then she gives that character voice and motivation and has a turn in narrating the story. Dungeons & Dragons is the iconic roleplaying game. When I explain my game writing pursuits to a “non-gamer,” I tend to give D&D as a point of reference, but I try to explain that my games are a little different.

Science fiction and fantasy is still covered in RPGs, but they have come a long way since TSR first published Dungeons & Dragons in 1974. They may be about amnesiacs with superhuman powers on the run as in Meguey Baker’s Psi Run, a budding romance as in Emily Boss’ Breaking the Ice, or child soldiers in World War II Warsaw as in Jason Morningstar’s Grey Ranks. These games have a common key element: they tell the adventures of heroes, big and small, who overcome great odds in pursuit of goals such as fortune, ideals, or love.

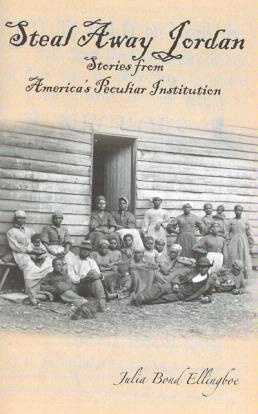

The first game I wrote was Steal Away Jordan: Stories of America’s Peculiar Institution. In the spirit of a slave narrative, a uniquely American hero’s tale, players collectively tell stories of African American slaves in antebellum America. Admittedly, the game was a hard sell at first. RPGs these days feature a great variety of themes and genres, but slavery in the antebellum US is a still a touchy subject. But in the game, the players, all slaves, have a great deal of narrative freedom in describing harrowing events. As an adventure story, it’s designed to be engaging without trivializing the suffering the characters experience or witness. Adding a bit of fantasy in any fiction is a useful device that helps readers engage with difficult issues at a safe distance, so in keeping with the tone of the setting, players in Steal Away Jordan can incorporate elements of African American folklore and superstition such as meeting the Devil at the crossroads. The game isn’t mean to be a guilt trip. It’s a heroes’ tale where the heroes, not unlike the traditional fighters or elven rangers of D&D, rise above their circumstances in pursuit of prosperity, freedom, and love.

Another claim I have heard about the subject itself was “this isn’t my history.” I assume this sentiment derives from the disconnect we attempt to make from traumatic and ugly events in American history. However, African American history, from the Middle Passage to the Civil Right movement, is American History. For example Crispus Attucks, an American slave and the first person to be fatally shot by the British during the Boston Massacre, is not just an African American, Native American, or Massachusetts historical figure, he is an American historical figure. Many of the facts of his life are lost to time. Over time, poets and storytellers have filled in the blank spaces with details that we can all identify with. Ultimately he has come to symbolize the sacrifices and struggles against oppression of Americans in the War of Independence.

I’m a descendent of slaves. When I think of the voices of slavery in America, I first think of the voices of the slaves, then of the slave owners. It’s a part of American history. From autobiographical accounts of slavery like Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave to fictional neo-slave narratives like Marlon James’ Book of Night Women, I recognize the voices as “my people,” but my people don’t own the history. We’re all descendants of slaves.