Phytophthora infestans is no run-of-the-mill plant pathogen. Given the right conditions it can down a field of tomatoes or potatoes in days. That’s what we saw here in 2009. It did much worse to potatoes in Ireland in 1845. Before the mid-1800’s P. infestans, or late blight, was unknown outside of the Andes. Global trade in seed stocks ended that with devastating consequences. I’m not speaking of the exodus and starvation of the Irish. I’m speaking of the unnecessary wearing of green around St. Patrick’s day and the irresistible urge to claim one’s Irish heritage no matter how slight.

Late blight has shown up in western Massachusetts again and my plants are not immune. I’m careful, but apparently not careful enough: I rotate my crops, I always grow certified seed (instead of buying plants from a trenchcoated guy with a rash in an alley), I give my plants plenty of fertilizer and water with a soaker hose (though nature waters from above). This year I even planted two resistant varieties: Defiant and Mountain Magic (both from JSS).

What do I do wrong? My tomatoes grow too close together so they stay wet for too long; P infestans loves wet and dark. The varieties that I grow in cages sprawl a bit and touch each other too much (like kindergartners). When the last bout of rain hit, the infestans swept right in.

I noticed a few of the sunken black necrotic lesions and cut them out. One variety of romas, San Marzano, seems particularly susceptible and I had to remove several plants, though I saved a few dozen fruits. Now I have to decide whether to bring in the big guns: copper or Bacillus subtilis. Copper works for awhile by preventing new infections. B. subtilis induces the plant’s systemic resistance which can fight off the disease, but really isn’t particularly effective.

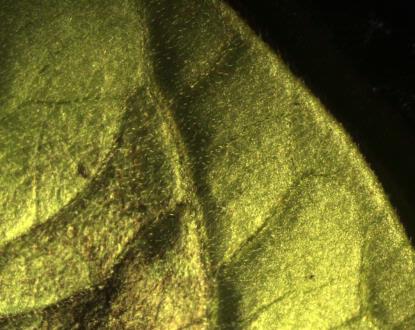

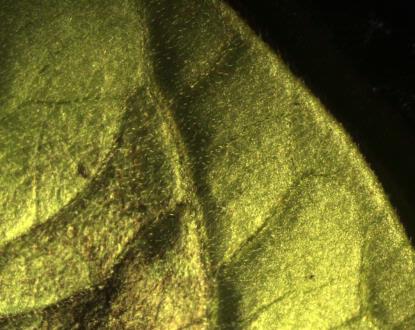

On my way to making the decision I brought some leaves into pointy-head headquarters to have a look under magnification. What I saw amazed me.

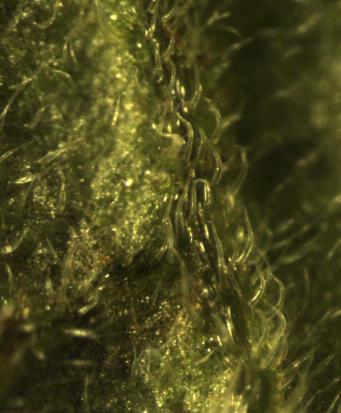

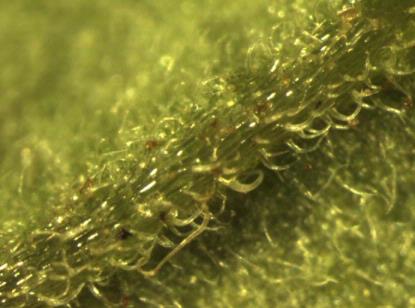

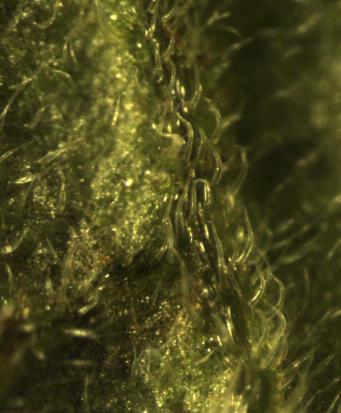

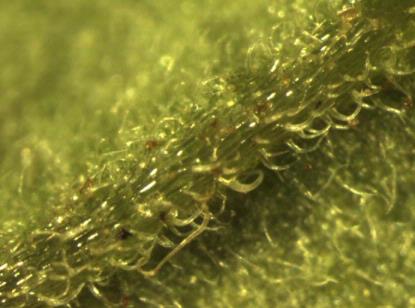

As even a cursory inspection reveals, tomato plants are fragrant and covered in hairs. Up close the trichomes (hairs) come in at least three types. There are those that look like hooks, bent over to catch on things. Some look like spikes sticking straight up. Then there are yellowish brown balls held in the air; these release the fragrance.

When I zoomed in really close, it looked like an alien Dr. Seuss forest. I jumped back in my chair when a mites far smaller than the trichomes crawled into view. The most stunning was the sporangia of the infestans swaying around in the breeze. At low magnification I could see all of these whispy hairs swaying back and forth in between the trichomes. These release the spores that spread the disease.

P. infestans is an oomycete. In some ways they are like plants and in some ways like fungus. Their eating habits are fungus like as they digest plant tissue, but their cell structure is more like a plant. In fact, they probably evolved from more plant like creatures and learned to eat like this later. All this is fascinating, sure, but now I’ve got to harvest as many tomatoes as I can before it wipes them all out. I’ve got my fingers crossed.

Phytophthora infestans is no run-of-the-mill plant pathogen. Given the right conditions it can down a field of tomatoes or potatoes in days. That’s what we saw here in 2009. It did much worse to potatoes in Ireland in 1845. Before the mid-1800’s P. infestans, or late blight, was unknown outside of the Andes. Global trade in seed stocks ended that with devastating consequences. I’m not speaking of the exodus and starvation of the Irish. I’m speaking of the unnecessary wearing of green around St. Patrick’s day and the irresistible urge to claim one’s Irish heritage no matter how slight.

Late blight has shown up in western Massachusetts again and my plants are not immune. I’m careful, but apparently not careful enough: I rotate my crops, I always grow certified seed (instead of buying plants from a trenchcoated guy with a rash in an alley), I give my plants plenty of fertilizer and water with a soaker hose (though nature waters from above). This year I even planted two resistant varieties: Defiant and Mountain Magic (both from JSS).

What do I do wrong? My tomatoes grow too close together so they stay wet for too long; P infestans loves wet and dark. The varieties that I grow in cages sprawl a bit and touch each other too much (like kindergartners). When the last bout of rain hit, the infestans swept right in.

I noticed a few of the sunken black necrotic lesions and cut them out. One variety of romas, San Marzano, seems particularly susceptible and I had to remove several plants, though I saved a few dozen fruits. Now I have to decide whether to bring in the big guns: copper or Bacillus subtilis. Copper works for awhile by preventing new infections. B. subtilis induces the plant’s systemic resistance which can fight off the disease, but really isn’t particularly effective.

On my way to making the decision I brought some leaves into pointy-head headquarters to have a look under magnification. What I saw amazed me.

As even a cursory inspection reveals, tomato plants are fragrant and covered in hairs. Up close the trichomes (hairs) come in at least three types. There are those that look like hooks, bent over to catch on things. Some look like spikes sticking straight up. Then there are yellowish brown balls held in the air; these release the fragrance.

When I zoomed in really close, it looked like an alien Dr. Seuss forest. I jumped back in my chair when a mites far smaller than the trichomes crawled into view. The most stunning was the sporangia of the infestans swaying around in the breeze. At low magnification I could see all of these whispy hairs swaying back and forth in between the trichomes. These release the spores that spread the disease.

P. infestans is an oomycete. In some ways they are like plants and in some ways like fungus. Their eating habits are fungus like as they digest plant tissue, but their cell structure is more like a plant. In fact, they probably evolved from more plant like creatures and learned to eat like this later. All this is fascinating, sure, but now I’ve got to harvest as many tomatoes as I can before it wipes them all out. I’ve got my fingers crossed.

Related