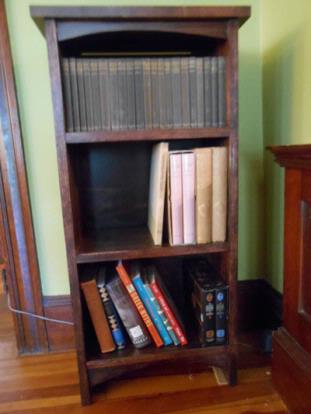

I have a new bookshelf. It modestly greets all who enter the house. The top shelf holds, perfectly, an old set of cloth-bound books of walking tours of English counties. Other random favorites with handsome spines populate the lower shelves.

What’s special about this shelf is that I made it. Bear with me: I’m bragging, although it’s a dubious honor to have completed this small project over the course of several months, taking weekly classes at a local craft school that offers courses to the community at amazingly low prices. New to all the tools and new to furniture making, I needed supervision for most of what I had to accomplish.

Beyond provoking your admiration, I’d like to share some thoughts about education I’ve had since I finished my shelf. I spend a lot of energy inwardly and outwardly bemoaning my own child’s public school education experience that is sitting at his desk completing worksheet after worksheet. Math is something you do on paper. Language is read and written and involves list of words with prefixes and suffixes in common, again mostly on paper; speaking and listening are secondary and incidental.

I know this approach is at odds with his most basic drives as a curious person and I am confident that the same is true for many of his classmates. His favorite school time activities are gym and art—I’ve heard many parents say the same of their children. I accept that, given the circumstances, it’s my job and his father’s job to introduce him to hands-on experiences, to invite him to make things, to be sure he gets his hands dirty in soil in the spring and makes snow-forts in the winter, to create opportunities for him to enjoy the outdoors and play with water, rocks and sticks.

But why is the public school education so devoid of hands-on learning? Was there a time in the history of American public school education when making things (anything!) was a central component of the elementary school curriculum? Or was that kind of learning happening in such an active way in most households, say, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, that there was a basic assumption that children were also learning skills? Let us table these questions for now and consider a few well-known K-5 education models we’ve heard about:

Montessori

Developed by Italian physician, philosopher, and educator Dr. Maria Montessori in the early twentieth century, this pedagogy, which is active all over the world, emphasizes several key elements: multi-age classrooms, the engagement of all of the senses, movement, the use of specially designed “learning materials” that engage children at multiple levels of complication and abstraction, and classrooms that are meticulously designed to encourage independent learning with limited need for teacher intervention. Hands-on learning is key in this model, and the approach is more firmly developed for pre-K and elementary aged learners. The Montessori approach is not typically offered in public school settings, but to date there are 459 public Montessori schools in the US.

Waldorf

Based on the educational theories of Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), the Waldorf educational model is meant to engage the hearts, heads, and hands of students and encourage the development of socially and morally responsible adults. The first Waldorf school began in Germany in 1919 and was founded for the purpose of educating the children of factory workers; working-class access to this model was a founding principle (whereas now in the US the Waldorf model is offered only in private school settings). Multi-sensory experiences are emphasized: Music, movement, art making, handwork, gardening, and woodworking are introduced at the elementary level, and natural materials such as wool, wood, and bees wax are made available for creative play and skill building activities. Electronic devise use is discouraged in lower grades. The Waldorf model has a spiritual basis as well, with Steiner’s Anthroposophy, a philosophy that seeks to join a quest for spiritual clarity with the rigor of the scientific method, serving as a founding belief.

Unschooling

Today many homeschooling parents opt for this approach, which relies on the theory that children learn most effectively when they are permitted to follow their natural inclinations and encouraged to view lived experiences as educational ones. Practitioners of unschooling reject formal curricula and evaluation models and often introduce the child-learners in their care to interesting experiences and outings, household responsibilities that will increase skills, and hands-on learning.

Outdoor Education Practices

An offshoot of Experiential Education practices, Outdoor Education generally occurs in camp settings, after school programs, preschools, and are not included in the typical American public elementary education, although there are charter schools that focus on outdoor education and environmental education as major areas of focus. Outdoor education programs provide opportunities for students to connect with nature, work in teams, gain skills with outdoor living (camping, fire building, hiking), and learn about the plants and animals of various landscapes. Early proponents of outdoor education include Henry David Thoreau, John Muir, and John Dewey.

Charter Schools

Charter Schools are independent public schools that run under the authority of state departments of education, receive allotment-per-pupil funding (which controversially siphons funds from traditional public schools), and are subject to state regulations and evaluation tests, such as MCAS in Massachusetts. However, they enjoy greater freedom for the development of curricula, they do not report to local school boards, and freedom in teaching methodology is afforded the professionals who run these schools. They are often founded as creative alternatives to the existing public schools. Hands-on learning is an oft-stated principle for charter schools. Charter schools do not have tuition fees, but students are selected using lottery systems and enrollment is not guaranteed to interested parents. There are 81 charter schools in Massachusetts

Magnet Schools

Magnet Schools differ from Charter Schools in that they run under the auspices of local school boards. They too receive allotment-per-pupil funding from the state but also receive federal funding from specific grants created to encourage thematic learning strands, such as environmental education, arts, or technology. Magnet Schools have more freedom to adopt “alternative education” pedagogies such as Montessori.

* * *

The traditional district public school today is an offshoot of the US Common School movement which introduced school systems overseen by state boards in the 1830s. The MA State Board of Education’s founding secretary was Horace Mann (1796–1859), who in that position became editor of The Common School Journal, supporting the merits and goals of universal public education. The main principle at work was open access and the learning of basic skills in mathematics, reading, writing, geography, and (then) religion. Attending school did not become compulsory until the 1920s.

It seems fairly clear from my cursory research into the history of public education in the US that the concept of “hands-on” learning was not in play in the early-mid nineteenth century (or earlier). “Education” was comprised of basic subject areas (as it it is organized now), with generalized content giving way to increased specialization and disciplines in secondary school. The value of “hands on learning” in a school setting for young children is a more modern concept introduced at the turn of the 20th century. And now, over 100 years later, that specific educational value is still alternative, not mainstream, and offered in more specialized private schools, charter schools, and magnet schools.

But the language of this value exists within the discourse of the MA public schools. Take this excerpt from page 26 of the Massachusetts Arts Curriculum Framework (a 175 page document):

Learning by Doing

Students learn about the arts from the artist’s perspective by active participation — they learn by doing. They come to understand the specific ways in which dancers, composers, musicians, visual artists, or actors think, solve problems, and make aesthetic choices. Massachusetts schools should educate students to think like artists, just as they teach students to think like writers, historians, scientists, or mathematicians. Learning in, about, and through the arts can lead to a profound sense of understanding, joy, and accomplishment. It is important that students learn to express and understand ideas that are communicated in sounds, images, and movements, as well as in written or spoken words. Sequential education in any of the arts disciplines emphasizes imaginative and reflective thought, and provides an introduction to the ways that human beings express insights in cultures throughout the world.

At my child’s school, students get to learn by doing in art class 45 minutes a week. And now to circle back to my bookshelf. Perhaps the bookshelf itself is a suitable metaphor for the excellence of hands-on learning: a practical object that contains within it, as a framing principle, multiple opportunities for additional content and flights of the imagination. Our children will have access to opportunities to make their own bookshelves as adults or high school students at vocational schools. But what opportunities to join the mind with the hands are being missed by elementary school aged children? Too many, to my mind.