In the latest in a series of reports released this spring, the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned again that governments are not doing enough to avert the profound risks associated with rising levels of carbon in our atmosphere. The national assessment of climate report released soon thereafter in Washington states that these risks are no longer merely theoretical or far in the future. We are already experiencing higher temperatures, greater precipitation and more frequent and intense winter storms.

President Obama says the impetus for taking action must come from the citizenry. Congress will not act on its own. We know this, of course. So where is the grassroots movement to save our planet? Why is it that the vast majority of us blithely (or in some cases, perhaps, anxiously) go about living our high energy-consumptive lives as if climate change were someone else’s problem to solve?

Nearly a half century ago the human ecologist Garrett Hardin put forward an economic theory he called the “tragedy of the commons,” according to which individuals acting independently and rationally as regards their own self-interest would inevitably behave in ways detrimental to the long-term interests of the population as a whole. Problems of this sort, Hardin explained, have no technical solution. They require a change in our values.

Hardin’s primary concern was human overpopulation, about which there was a much greater hue and cry in 1968, when Hardin’s theory was published in the journal Science, than today. But the theory applies in any situation involving the exploitation by private individuals of a public resource.

Imagine a town common where local farmers are allowed to graze their cows. The farmers know the common can support only so many cows and so they have an understanding that each farmer will graze only an agreed upon number to avoid overgrazing. In this situation, it is in each individual farmer’s rational self interest to graze more than the agreed upon number of cows on the common even though this may lead to overgrazing because the benefits of grazing the additional cows accrue entirely to the individual farmer while costs of overgrazing are shared by all. Hence, the “tragedy” of the commons.

Consider our fisheries for another example. If left to his own devices, it is in the interest of any individual fisherman to catch as many fish as possible, or to fish during spawning season, say, because the benefits of doing so accrue entirely to him while the costs of the depleted fishing stocks that may result are shared by all the other fishermen. This is why we enforce fishing regulations, including the occasional closing of fisheries.

The same principle applies when it comes to releasing carbon into the atmosphere. The benefits in lower costs and higher profits of burning coal instead of going solar, say, accrue to the energy producer or consumer while the costs of increasing global warming and air pollution are shared by everyone on earth.

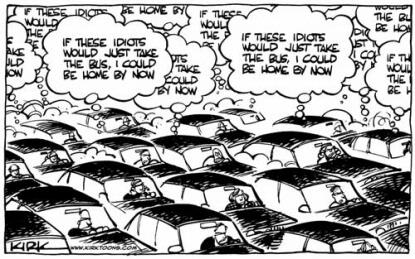

The very same kind of rational calculation works in reverse in our individual efforts to reduce carbon emissions. The inconveniences of “going green” are borne by the individual who hangs out laundry, say, instead of using the clothes dryer or takes the subway to work instead of driving, while the benefits are shared by all – including the most energy-profligate among us.

The incentives run in the wrong direction in both cases. This is why we need government intervention. According to the IPCC Report, there is still time for mitigation strategies to work, but the situation is urgent.

President Obama’s recent decision to use his executive authority to limit carbon emissions from coal-fired power plants is a step in the right direction, but it simply will not be enough.

The perverse incentives of carbon pollution have to be reversed. The most obvious and simplest way to do this is to impose a carbon tax. Make it more expensive to emit carbon and producers and consumers alike will find ways to reduce their “carbon footprints.” And the revenue from a carbon tax can be used to develop green energy solutions as well as for infrastructure improvements needed to adapt to the effects of climate change that are surely coming and cannot be forestalled.

But this too is only a palliative remedy. What is needed, in Hardin’s words, is an “extension of morality,” a radical transformation in our values away from consumerism and continuous economic growth and toward sustainability. That is a subject for a future post.

Cartoon by Kirk Anderson. Posted with permission of the artist.