This summer’s keynote Shakespeare is A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which was the company’s very first production, in 1978, when Simotes himself played Puck. It’s a big, brash staging with an audacious concept and a large cast. But most of the eight-play season is quite the opposite: compact, small-cast pieces that focus in on text and texture. Julius Caesar has a cast of seven and Romeo and Juliet fields just six. Both parts of Henry IV are being condensed into one evening.

And two Shakespeare plays aren’t by him at all: the screwball homage-cum-sendup The Complete Works of William Shakespeare (Abridged)—which, like Midsummer, has had several outings here over the years and, Simotes says, “helped to establish our style of comedy”—and Shakespeare’s Will, a fanciful biography of the poet from the viewpoint of his neglected wife. These two have a total cast of four.

In Simotes’ view, the maxim “less is more” applies here. The pared-down approach derives from founder Tina Packer’s “Bare Bard” concept, which arose from the company’s need for an indoor performance space in their first home at Edith Wharton’s estate in Lenox, just down the road from the company’s present digs. The Mount afforded an expansive open-air playing area that accommodated audiences in the hundreds, but the only available indoor space was the tiny Stables.

That limitation, says Simotes, was in fact a gift. “It gave the company a chance to explore the text and our training methodology in a theater that was both protected from the elements and very intimate with the audience.” And that actor/audience relationship, forged from necessity, turned out to be “groundbreaking for our performances and style of theater.”

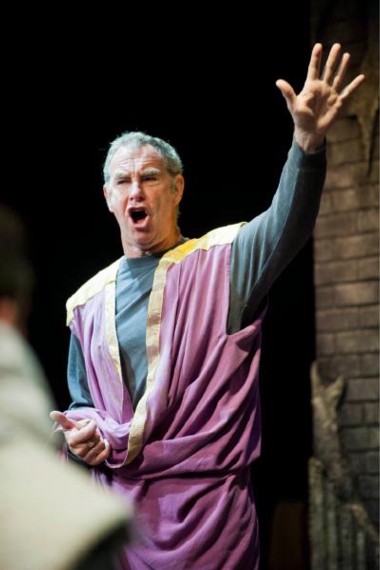

Julius Caesar, performed in the Elayne P. Bernstein Theatre—the modern successor to the Stables—is the epitome of the Bare Bard method: a taut, headlong plunge through the tale of blood and honor that has actors stepping in and out of characters, and costumes, before our eyes. My favorite of these moments comes in act two, scene one, with Brutus’ servant asleep on the floor as his wife enters. Kristin Wold, as the servant, rises and dons the blanket that was covering her to become Portia in her dressing gown.

That approach gets a real workout in Romeo and Juliet, which follows up its spring tour of New England schools with a full run back where S&Co began, on the grounds of The Mount. Each member of the versatile cast of young professionals, directed by Jonathan Croy, plays three or four parts, displaying vivacious energy and impressive swordplay. Judicious cuts and a lively pace turn “the two hours’ traffic of our stage” (usually more) into a crisp 95 minutes, punctuated with moments of comedy that brighten the piece without losing its heart.

Croy is also the director of one of the two shows that are “grounded in Shakespeare.” Complete Works (Abridged) is exactly (sort of) what it says it is: a lickety-split three-actor romp that at least touches on every work in the canon, from complete-plot overviews of R&J and Hamlet to the entire history cycle played as a football game. Josh Aaron McCabe, Ryan Winkles and Charls Sedgwick Hall are in almost constant motion throughout, aided by two equally lively offstage dressers.

When I visited a rehearsal last month, they were running (literally) through the madcap capstone of the show: Hamlet played backwards. With three seasoned S&Co veterans bouncing gags off each other, Croy told me with a smile, “At this point in the process, I just try to stay out of the way,” adding that actor input, from ideas for comic bits to insights into tragic characters, is fundamental to the company’s way of working.

Shakespeare’s Will, an altogether quieter piece, plays as loosely with Shakespeare’s life as Complete Works does with his plays. Vern Thiessen’s one-person show about Anne Hathaway lets us imagine, through her recollections, the life of a 16th-century small-town woman who married a dreamer and stayed behind in Stratford to raise his children while he followed his star to the playhouses of London. In Kristin Wold’s kaleidoscopic performance we find a devoted mother and not-so-faithful wife who, on the morning of her husband’s funeral, is about to find out that she’s been all but disinherited.

The Head That Wears the Crown

Hands up, everyone who has seen Henry IV Part II. Me neither. It’s the orphan twin of Shakespeare’s two-part exploration of kingly succession. Part I is far more frequently staged, full of comic shenanigans with crown prince Hal and his dissolute mentor Falstaff while the aging king despairs of his prodigal son and fights off an insurrection spearheaded by gallant young Hotspur, who’s more fitted for kingship than the delinquent prince.

Part II is in some ways more of the same—battles and monkeyshines—but for Jonathan Epstein, the two are an essential whole: “To me, Part I without Part II is like Lear ending at the storm scene or Hamlet ending when he goes to England. Those would be incomplete, and it’s really clear to me that this would be incomplete too.” Although the first part concludes with a dramatically satisfying battlefield victory, key themes and plot threads are left unresolved, especially the father/son conflict and Hal’s growth to become Henry V.

Epstein is the director and adapter of Henry IV, Parts I & II. He also plays the title role, though as he told me recently, “It’s one of the shortest roles in the play. He’s not really the subject of the story, but he’s the milieu.” This compressed version is not simply an edit but “a composition and adaptation” that conflates characters, rearranges scenes and speeches for dramatic effect, and scatters anachronisms indiscriminately.

The somewhat faceless nobles attending the king—“guys in beards and fur,” as Epstein puts it—have been merged into a single personal assistant, and a woman at that. (He’s added a couple more women’s parts to make up for Shakespeare’s dearth.) The 13 cast members double up on roles, often playing complementary or contrasting characters—for example, the actors portraying brave Hotspur and his noble wife come back as the comic barflies Pistol and Doll Tearsheet. As for anachronisms, a character who brandishes a sword in one scene might be reaching for a cellphone in the next.

“I hope the audience doesn’t get cranky,” Epstein says. “The logic works for me, but we don’t spend a lot of time explaining why now cellphones, now broadswords. We’ve just set the scenes where we think they’ll be most vivid.” He admits the production asks a lot of its audience, not only for its liberties but its length. Both parts of Henry IV, uncut, would run over six hours. Epstein has aimed for a running time of three hours total. “That hurts, for someone who loves them as much as I do,” he said, “but it’s a chance for people to see the whole story.”

It also represents a challenge to theatergoers, he says: “We as audiences have gotten a little lazy about how much energy we’re willing to put into a theatrical event. Here, the audience has to buy into what we’re doing, and then accept that we’re going to be doing it for quite some time.”

For Tony Simotes, that challenge, and the whole season’s arc, represents an opportunity “to see the plays through 21st-century storytelling. These plays are living and breathing art forms. The artist’s vision is to imagine a stage world that makes Shakespeare’s 400-year-old language as meaningful and inspired as it must have been to his audience in the 1600s.” In dreaming up this birthday bash of a season, he says, “I wanted our audiences to have many ways to immerse themselves in Shakespeare & Company’s vision of where we’ve been, and take a peek at where we’re going.”•

All productions play in repertory through this month at Shakespeare & Company, 70 Kemble St., Lenox, (413) 637-3353, shakespeare.org.

Chris Rohmann is at StageStruck@crocker.com and his StageStruck blog is at valleyadvocate.com/blogs/stagestruck.