In 1763 Great Britain had won the Seven Years’ War against France. With the Treaty of Paris that followed, Britain maintained its American territories and all of Canada was surrendered by the French. This vast, newly-acquired area increased the size of British North America and the tiny island’s empire as a result. That is not to say, however, that Canada’s shift from France to Great Britain was an easy transaction.

It was a precarious situation because of the social differences between the two powers. For starters, most of the people living there were French. And one can be certain that the lingua franca of Canada was just that: La lingua Franca – French. I can’t imagine that an English-speaking minority governing Canada was an easy task that went over well with the locals. Even more problematic than any gaps in communication was the religious divide. The French Canadians were predominantly Catholic. Their new English government was not.

These differences between the historic French Canadians and their British administrators are similar to the Israeli/Palestinian divides today. A land owned by Britain prior to the end of WWII, the State of Israel was created in 1948 in order to give the recently devastated Jewish people a homeland. While there certainly was a sizable Jewish population in the British Mandate of Palestine at the time, the majority of the locals were Arabs: a people with a different language and religion than their newfound Jewish administrators.

Ignoring the proceeding tumult from that point to today, Israel still faces the issue of the future of its nation. Some support total Israeli control of the remaining Arab areas of the West Bank and Gaza. Others propose a more utopian, one state solution, which would be completely blind to race or religion. There are also attempts to form two completely separate states, one Israeli and one Palestinian, although the road to this solution has been marred by perpetual violence from both sides, such as the most recent crisis in Gaza.

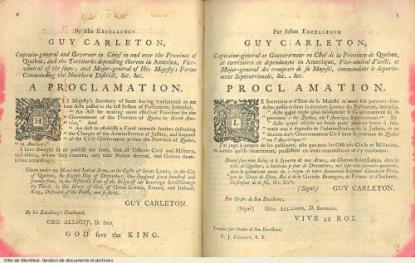

But, as it was Britain that essentially laid the foundation for the conflict between Israel and Palestine in 1948, perhaps the solution to the Gaza crisis and ongoing struggle lies in British history. When Britain had inherited Canada from the spoils of war, they had initially tried to force the people to assimilate into British culture. French residents of Canada who did not leave became subjects of the British Crown, and in order to hold public office were required to reject the Catholic Faith. After realizing this ethnic policy was not working, the British passed the Quebec Act in 1774. This granted French Canadians the free practice of Catholicism, allowed for the French legal system to continue in Canada, and provided for the preservation of French culture. Some of the exact text was as follows:

IV. And whereas the Provisions, made by the said Proclamation, in respect to the Civil Government of the said Province of Quebec, and the Powers and Authorities given to the Governor and other Civil Officers of the said Province, by the Grants and Commissions issued in consequence thereof, have been found, upon Experience, to be inapplicable to the State and Circumstances of the said Province, the Inhabitants whereof amounted, at the Conquest, to above sixty-five thousand Persons professing the Religion of the Church of Rome, and enjoying an established Form of Constitution and System of Laws, by which their Persons and Property had been protected, governed, and ordered, for a long Series of Years, from the first Establishment of the said Province of Canada; be it therefore further enacted by the Authority aforesaid. That the said Proclamation, so far as the same relates to the said Province of Quebec, and the Commission under the Authority whereof the Government of the said Province is at present administered, and all and every the Ordinance and Ordinances made by the Governor and Council of Quebec for the Time being, relative to the Civil Government and Administration of Justice in the said Province. and all Commissions to Judges and other Officers thereof, be, and the same are hereby revoked, annulled, and made void, from and after the first Day of May, one thousand seven hundred and seventy-five.

Unfortunately, Canada’s troubles were not entirely remedied by a mere document. With Britain being the lawful parent nation of Canada, waves of British immigration followed and this complicated matters further. Canada soon had a sizable mix between Catholics and Anglicans, Francophones and Anglophones. The once-French areas of Canada were then officially split, with two contrasting regions coming to be known as Upper Canada and Lower Canada.

The divide went even deeper, beyond language and religion. As the Quebec Act allowed for the preservation of French culture, this meant that French Canadians could remain in their established economic system. The economies of Upper and Lower Canada were drastically different and this created a host of problems. Upper Canada consisted of wealthier British and United States immigrants. These Anglo-American residents were committed to the free market economic systems of their former nations, and were eager to modernize Canada as such. Unfortunately for them, the residents of Lower Canada were living under the more French feudal/agricultural system. With an anachronistic economic system, Lower Canada impeded the Nation’s economic advances.

Soon the “backwards” French Canadians were drawing the ire of their British counterparts. Englishman John Lambton, the 1st Earl of Durham was sent by the British Crown to Canada to survey the population. In his Report on the Affairs of British North America, Lord Durham establishes that the French Canadians are an entirely separate race from their British neighbors. When violence began to emerge between the two demographics, Durham suggested that the solution lay in overwhelming the French population with a massive influx of British immigration, a culture he suggests is better.

One doesn’t need to be a scholar of history or politics to draw parallels from this situation to the one in Israel and Palestine today. That Jewish complaints of their Arabian counterparts as violent, backwards, and economically lagging are surprisingly similar to British complaints of the French Canadians. Israel is vying to be a leading, Democratic nation — much as the residents of Upper Canada wanted their country to be — and complicating that goal are the quarrels with neighboring Arab Muslims that have been continuing for decades.

Harmony in Canada did not flourish until after full-scale rebellion. The French lower classes of Lower Canada organized, and rebelled against their overseas masters in 1837. In a surprise twist of history, the Upper Canadians saw this as an opportunity to break free from Britain altogether and joined the French Patriots a year later.

Unlike the earlier and successful American Revolution, the Canadian one failed. In the aftermath, Britain took a firm stance to end the social discord between Upper and Lower Canada by merging them into one state: The United Province of Canada. This new province would eventually serve as the foundation for what is today’s Canada, but the nation, no matter what its size or name, has always been respectful of the remaining French culture within Quebec. This can be seen by a simple visit to Montreal or Quebec City, where road signs, restaurant menus, and everyday business is conducted in French and English is the secondary language.

Perhaps this is the best solution for Israel and Palestine: that Palestine would work best as a province within the nation of Israel. Road signs, restaurant menus, and other materials could be printed in the dominant language of Arabic. Palestinian business would be conducted in Arabic, and the people still be able to maintain their Muslim heritage, while at the same time remaining a part of a larger Jewish state. This would require a firm Israeli stance, requiring the annexation of both Gaza and the West Bank. Israel, however, would also need to be fair and at the same time allow Muslim Arabs to serve in the public sphere and have the same rights as Jews. And while violence rarely produces anything to be proud of, Israel may need a Palestinian uprising before it can rightfully claim these areas as its own, or otherwise lose their authority altogether.

Photo: Bilingual excerpt from the Quebec Act, 1774