“I don’t want to die too soon.” These words spoken by a young woman, the same age and complexion as Michael Brown, were voiced from a deep and lonely place. As a teenager facing adulthood and entering college, she identified with Brown, who no longer had a future to contemplate. It was gone, taken in a second. Her tomorrow still beckoned, but she recognized, perhaps as never before, that time and choice matter. And so does finding commonality with the people on the planet at the same time as you, so that you do not immediately and irrevocably become a threat and target to hit and extinguish.

The pain of being repeatedly seen as a thing and not as person was center stage with Brown’s death. Everywhere we looked, guns were trained on unarmed people. In one of those pictures from Ferguson, a young man faces an army of policemen. The frame of the picture is not big enough to contain them all. Outnumbered, he is confronted with raised, pointed and loaded weapons. And the men holding these murder machines wear combat gear. They are protected and invulnerable. He is not.

His hair is in dreads, and his complexion coffee-colored. He wears basic working-class denim, not the trendy ripped, faded version. His hands are held in surrender as he faces an endless line of men promising him death if he does not abjectly and immediately comply.

His back is to the camera, and he is faceless. Wherever he is going, whether to work or college, he immediately becomes a hostage. Over and over, this saga is enacted on the streets of America. Walking while black can turn at any moment into a danger scenario, a prelude to death.

He is unquestionably guilty for being in the wrong place at the wrong time, which could be anywhere outside his door, and if he makes the wrong move, his life and future are history. Bottom line, he is routinely seen as a threat. More often than not in popular imagination, he and his kind are criminals.

In Missouri, the country’s heartland, the saga of good guy, bad criminal plays out. A quick policeman or a self-deputized citizen decides not to risk it when faced with a possible criminal. It happened in New York with Eric Garner who was strangled while selling cigarettes, in Detroit when Renisha McBride got her face blown off after asking for help, and in Florida when Trayvon Martin was shot by a wanna-be policeman who thought the kid in the hoodie was too far from home. Before that, Jordan Davis was killed for playing his music too loud. And two days after bullets ended Michael Brown’s future, Ezzell Ford was killed in the streets of Los Angeles by two policemen as he suffered what most likely was a bi-polar attack. Ferguson is not an anomaly; it is the back-breaking straw in a repeating, heavy scenario.

These recurring scenes of public violence recall not only the disruptive times when little girls were fire bombed in southern churches but point also to a forgotten era when lynching was in vogue, and catching, killing, and burning accused criminals, usually olive and darker in complexion, was a national pastime. That happened in the 19th and 20th centuries. But this is the 21st century, the people of Ferguson say. Could this be occurring again, this targeting of suspicious people with faulty hair, complexion, neighborhood, and dress, and the on-the-spot loss of their lives, no questions asked?

That long-ago posse, the guys who lynched together like a band of brothers, were everywhere, south, north, west, east, and mid-west. They took pleasure in their job, and were lionized. Things got better for them in the turn-of-the-century spectacle era, when lynching was so well-supported and popular that it was staged as public carnival. Grace Elizabeth Hale details lynching’s carnival tone in her 1999 book, Making Whiteness. At the scene of a lynching, crowds gathered “not only to murder the victim but also to view the corpse, to mangle or disfigure it further in a highly ritualized fashion, to pose for photographs, and to enjoy musical performances and orations,” Amy Kate Bailey and Karen Snedker write in 2011 in The American Journal of Sociology. According to Hale, the crowds sometimes grew so large that transportation companies had to add extra trains to carry the excited traffic to the next killing site. Deaths, one after the other, were put on as public show, and the folks who missed the fun could read about it in the paper or see a souvenir postcard or hear the actual death agonies in short films.

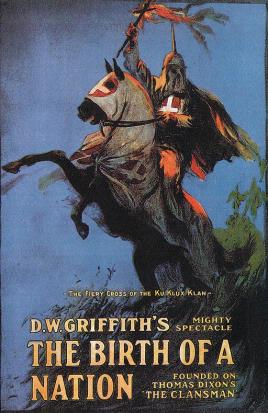

Hollywood’s first blockbuster film, Birth of a Nation, made the guys that lynched stars, triumphant in their white sheets and pointy hats. In 1915, Birth recast the south as victorious, flipping history on its head. Because the lynchers, with or without regalia, kept the killing going after the treaties were signed, they were heroes, folks said. In a few months, Birth will celebrate its centennial, but the trilogy of novels and a dramatized version, on which the film script was based, were written and circulated earlier.

Hollywood’s first blockbuster film, Birth of a Nation, made the guys that lynched stars, triumphant in their white sheets and pointy hats. In 1915, Birth recast the south as victorious, flipping history on its head. Because the lynchers, with or without regalia, kept the killing going after the treaties were signed, they were heroes, folks said. In a few months, Birth will celebrate its centennial, but the trilogy of novels and a dramatized version, on which the film script was based, were written and circulated earlier.

It is stunning to think about the similarities between then and now. The accused, sometimes female but mostly males with black and brown skins, was given an immediate death sentence. Once the job was done, which included claiming pieces of the body and bone as souvenirs, the posse would leave the remains of the victim exposed, as a sign of scorn. And Michael Brown’s body was left in the street for hours, and his reputation pulled into smithereens by hearsay. What separates lynching in the past from contemporary street killings such as Brown’s is that his body was not publicly burned to a crisp. From the 19th into the first half of the 20th century, lynching was a regular occurrence, happening with a frequency similar to what Isabel Wilkerson, the Pulitzer-prize winning journalist and author, cites in The Guardian. From 2005-2012, she writes, an African American has been killed by a white policeman every three or four days, and that is on the low side since many instances are unreported. Still, the rapidity and coincident regularity of the cases that do make it into public awareness is staggering.

And so people in Ferguson and across the country await a verdict. Were the six bullets ending the life of Michael Brown justifiable against a young man walking in the street who may or may not have committed a crime and who may or may not have died with his hands raised in surrender? In the past, the folks who enacted the lynching ceremony were given the benefit of the doubt without any substantiation of their word needed, and they were never liable for any death they exacted. So it is a great sign that police in Ferguson, Missouri have agreed to wear body cameras, which will mean that all versions of what is said to have happened will be documented, and competing versions of the truth can be compared and verified. Knowing that the eye of surveillance is on them, the police will have an extra incentive to insure that when the trigger is pulled, the provocation warrants the measure taken.

And now, a few more frightened sisters, mothers, and fathers can breathe easier and deeper in the expectation that their loved ones will be able to make it home safe and sound, and the phone will not ring with the news that someone in their family lies slain in the streets, left untended for hours.

In solidarity with the bereaved in Ferguson, Missouri, friends and family across the country are standing up, speaking loud and speaking together with unfettered hands and feet, eager for the killing to abate and for everyone, especially the younger generation who are their futures, to make it home in safety.

Barbara Lewis, an associate professor at UMass Boston, directs the William Monroe Trotter Institute for the Study of Black History and Culture. Trotter, descended from the Hemings-Jefferson line, gave his life to social justice activism. In Boston, he led protests against the incendiary images in Birth of a Nation.

Photos, top to Bottom:

(1) from James Allen ed., Without Sanctuary: Lynching and Photography in America (Twin Palms Publishers, 2000)

(2) Birth of a Nation poster, distributed by Epoch Film Co. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons